By Christina Vida

Nancy Toney of Windsor may have the distinction of being Connecticut’s last enslaved person. Born into slavery in Connecticut in 1774, she lived through the American Revolution and the War of 1812, saw a railroad transform her town, and witnessed the legal end of slavery in Connecticut in 1848. She died December 19, 1857, in Windsor, six years before President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation and eight years before the US outlawed slavery. A surviving portrait and headstone flesh out the story told by vital records, census data, and a will. But what did not survive are Nancy Toney’s impressions of her dramatically changed world or her years of servitude.

Toney’s Early Years

Nancy’s mother, Nanny, belonged to Reverend Andrew Eliot, minister of the First Congregational Church in Fairfield (then called Christ’s Church). Her father, Toney, belonged to Jeremiah Sherwood in nearby Green Farms. Church records show that their daughter Anna—later known as Nancy—was baptized on November 27, 1774, in Christ’s Church. By 1785, another wealthy Greenfield Hill resident, Hezekiah Bradley, owned Nancy. In September of that year, Bradley’s daughter Charlotte married Dr. Hezekiah Chaffee Jr. of Windsor. Bradley gave Nancy to his daughter as a wedding present to serve as the Chaffees’ household servant. Thus, by the age of 11, Nancy had been separated from her mother and father, relocated a long distance away from her family, and forced to tend to the needs of a prosperous Windsor family.

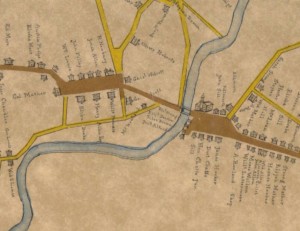

Detail indicating the homes of the Chaffee and Loomis families from a Map of Windsor, shewing the parishes, the roads, and houses by Seth Pease, 1798, Windsor – Connecticut Historical Society

Within six years, the Chaffees had completed their two-story home beside Palisado Green and had welcomed the births of their three children. In her late teens and early 20s, Nancy would have been running the kitchen, doing the laundry, and helping Charlotte raise young Abigail, Hezekiah, and Samuel. During this time, Dr. Hezekiah Chaffee Sr. lived next door in a three-story brick mansion and owned three enslaved women. In 1791, the elder Chaffee owned a “Negro Woman” who gave birth to a daughter, Betty Stevenson. Four years later, Dr. Chaffee Sr. purchased a 25-year-old woman, Sarah, from Jonathan Butler of Hartford. Based on their proximity, Nancy, Sarah, Betty’s mother, and young Betty might have shared the workload of the two homes and could have had some autonomy in their connecting backyards. But by 1810, Chaffee Sr. had manumitted Sarah, Betty, and her mother. Nancy Toney was the only slave in Windsor listed in the 1810 and 1820 federal censuses. We can only speculate why the younger Chaffee did not follow his father’s lead and free Nancy.

Later Years, Still Enslaved

Abigail Sherwood Chaffee Loomis inherited Nancy from Dr. Chaffee Jr. after his death in 1821. His will, dated 1818, specifically bequeathed “to my Daughter Abigail S. Loomis, wife of Col. James Loomis…my negro slave Nance.” In 1822, James and Abigail Loomis constructed an impressive brick house along the Broad Street Green in Windsor. Nancy was once again uprooted to a new home and once again provided an invaluable pair of hands in a bustling home, this one with five children ages 15, 13, 11, 9, and 7. A sixth child would follow in 1825. In the 1830 federal census, Nancy is surprisingly listed as a “free colored female.” Before she turned 46, the Loomises could have freed Nancy by certifying to the town that she was in good health and could care for herself. No extant Windsor records prove Nancy’s freedom as it is categorized in the federal census; therefore, it is possible that the Loomis family began labeling Nancy as a free person without actually granting her freedom. Why the Loomises would do this is still uncertain.

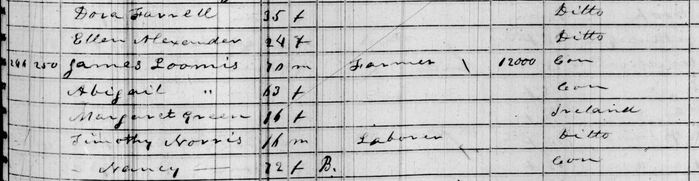

What is certain is that Nancy remained in the Loomis home. The 1850 US Census, the first to name residents other than the head of household, listed Nancy, a 72-year-old free black woman, residing with James and Abigail Loomis.

Detail from the 1850 US Census listing Nancy aged 72 – 1850 Connecticut Federal Population Census Schedules, National Archives and Records Service

Death and Legacy

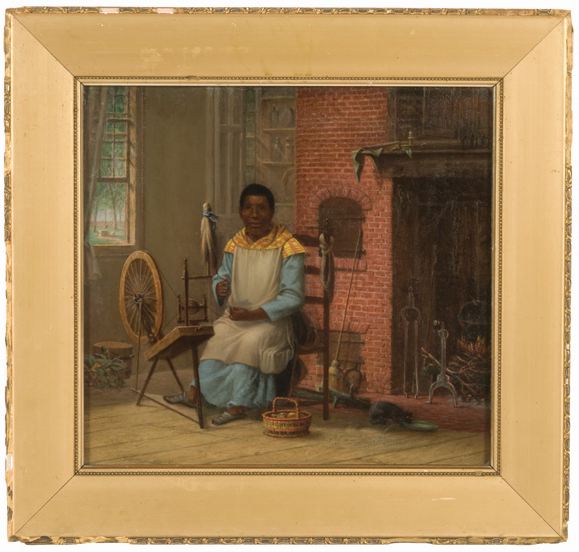

Seven years later, on December 19, 1857, Nancy died. Windsor’s death record lists her as an 82-year-old, single, colored female who was born at Greenfield Hill and died of consumption. The death record mysteriously names her as “Nancy Joyce”—possibly referring to a middle name—but the Loomis family erected a marble headstone emblazoned with the name “Nancy Toney.” Osbert Burr Loomis, a son of James and Abigail, painted a portrait of Nancy after her death. He portrayed her in work clothes, spinning yarn, seated in front of a hearth where she would have spent countless hours cooking, with a wash pail, broom, and work baskets surrounding her. While we know more about Nancy Toney than about many other Connecticut enslaved persons, the existence of the painting, the headstone, and the few surviving records are only a partial testament to Nancy’s lifetime of enslavement in the Bradley, Chaffee, and Loomis families. Nancy Toney’s years of service to families other than her own are worthy of remembrance. She is buried in Palisado Cemetery, a site on the Connecticut Freedom Trail.

Christina Vida is the curator of collections and interpretation at the Windsor Historical Society and a former assistant curator of George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 11/ No. 1, WINTER 2012/2013.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.