by Andy Piascik

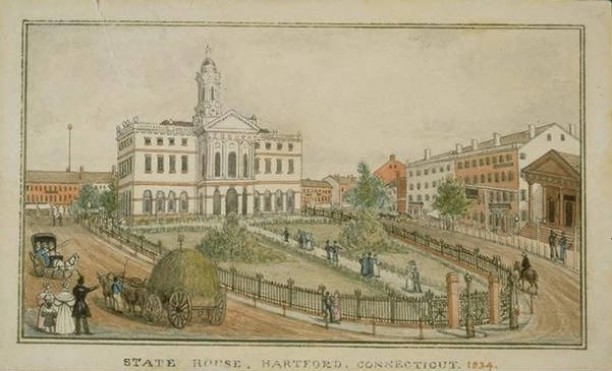

In 1784, as the American Revolution drew to a close, the new government of Connecticut passed the Gradual Abolition Act to address the issue of slavery in the state. The law freed none of the approximately 3,000 slaves in Connecticut but rather confined itself to the fate of future individuals born into servitude—the children of slaves—by stating that all such individuals born after March 1, 1784, “shall be free” upon reaching the age of 25.

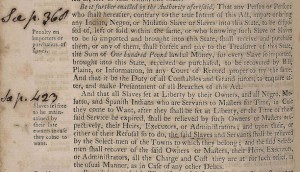

Detail from Acts and Laws of the State of Connecticut, in America: Slaves, 1784 – Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Used through Public Domain.

Ten years after passage of the Gradual Abolition Act, the state legislature considered and rejected a bill (forthrightly entitled An Act for the Abolition of Slavery in this State, and to Provide for the Education and Maintenance of Such as Shall be Emancipated Thereby) that called for the immediate outlawing of slavery in the state. Thus it was that slavery continued in Connecticut until 1848.

Nancy Jackson

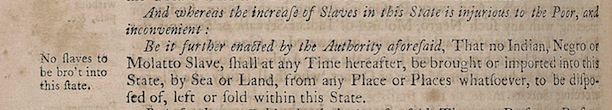

In 1837 when there were approximately 25 slaves in Connecticut, a black slave named Nancy Jackson living in Hartford petitioned the state for her freedom, claiming she was “illegally confined” by James Bulloch, a slaveowner from Georgia who lived approximately half the year in Connecticut. Bulloch brought Jackson (a slave born on his plantation in Georgia) to Hartford in 1835. Two years later, Jackson’s claim of freedom cited the Nonimportation Act, a state law passed in 1774. The law, the full name of which was the Act for Prohibiting the Importation of Indian, Negro or Molatto Slaves, stated that no slave could be “bought or imported” to be “disposed of, left or sold” within Connecticut.

Detail from Acts and Laws of the State of Connecticut, in America: Slaves, 1784 – Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Used through Public Domain.

Much of Jackson’s case hinged on interpretations of the simple word “left.” Bulloch claimed he was only in Hartford temporarily and intended to return to Georgia with Jackson, and therefore Jackson had not been brought to Connecticut to be “left.” Jackson’s counsel claimed that she had indeed been “left” in that she had lived in the state for two years consecutively, with no end in sight, while Bulloch traveled back and forth between Connecticut and Georgia.

Over the course of their deliberations, the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled out two possible extreme interpretations of the act and its wording. First, they discarded the notion that the slave must be left permanently in the state in order to meet the law’s intent. That interpretation would have made it possible for a slaveowner to bring a slave to the state with no time limit whatsoever on when the owner and slave might leave to return from whence they came.

The court also rejected a scenario where a slave might claim freedom during a temporary stopover in the state. However repellent they found slavery, the justices viewed the granting of freedom in such cases as a possible affront to slave states and slaveowners who, the court asserted, had the right to travel through Connecticut without risk to their property, even if that property consisted of slaves.

The Court Finds For Jackson

By a 3-to-2 decision, the court eventually found for Nancy Jackson, setting her free. The two justices in the minority interpreted the law to apply only to permanent residents of the state, as opposed to temporary residents such as Bulloch. The majority, however, opined that the law did not provide for slaves to be brought to Connecticut “for any time their owners choose.” To find for Bulloch, they wrote, allowed someone to “go abroad and hire slaves and bring them to labour in the state,” reinvigorating slavery in Connecticut.

A Portrait of Nancy Toney (1774-1857), oil on canvas, ca. 1862 – By Osbert Loomis, from the collection of the Loomis Chaffee School Archives, Loomis Chaffee School, Windsor, Connecticut. Used through Fair Use and Public Domain.

A year after the Jackson decision, in 1838, the Connecticut legislature increased the rights of blacks identified as fugitives. Connecticut did not abolish slavery, however, until 1848, when approximately six slaves remained in the state, including 74-year old Nancy Toney of Windsor. Study of the matter offers only incomplete records, but Toney may have been the last slave in Connecticut when she died on December 19, 1857, at the age of 83.

Bridgeport native Andy Piascik is an award-winning author who has written for many publications and websites over the last four decades. He is also the author of two books.