By Gregg Mangan

Henry Ward Beecher was a renowned clergyman, author, anti-slavery activist, and reformer in the 19th century. At a time when ministers played a prominent role in American life, Beecher connected with a generation of followers made uneasy by the rapid progress of industrialization. His exceptional oratory skills, sermons simple enough for any person to understand, and his humor brought him international notoriety and provided a platform from which he was able to launch a career of political activism and religious reform. Beecher was also embroiled in one of the most spectacular scandals of his day.

Life under a Famously Conservative Father

Henry Ward Beecher was born on June 24, 1813 in Litchfield to Lyman and Roxana Foote Beecher. At the time of Henry’s birth, Litchfield was one of the most prosperous communities in Connecticut and a place where adherence to strict Congregationalist ideals was seen as an essential means for reigning in man’s natural depravity. Henry’s father, Lyman Beecher, a preacher known for his conservative stance against the loosening of Calvinistic doctrine, led the moral crusade. Henry’s mother died when he was only three and he was raised in a house with 13 siblings, a domineering father, and a stepmother whom he feared. He emerged from early childhood a shy, inarticulate boy who longed for solitude and peace.

Henry Ward Beecher, ca. 1855-65 – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Lyman Beecher accepted a position at Hanover Church in Boston and moved his family to Massachusetts in 1826. Henry was considered a poor student at the Boston Latin School, and when his academic performance was deemed inadequate to meet college entrance requirements, his father sent Henry off to the Mount Pleasant Classical Institution in Amherst, Massachusetts. It was at Mount Pleasant that Henry received technical training in public speaking, bolstering his self-confidence and helping his boisterous sense of humor to emerge.

Entry into the Ministry

In 1830 Lyman sent Henry to Amherst College, an institution that specialized in the training of ministers. It was during these years that Henry began to develop his own interpretation of God’s will, one that emphasized God’s mercy and love as opposed to the fear and damnation preached by his father’s generation. Regarding his new approach, Beecher was quoted as saying, “If this love of God will not move you, the fear of God will not.” It was also during this time that he met schoolteacher Eunice Bullard, who eventually became his wife.

Upon graduating from Amherst, Henry moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, to join his father who had taken a position as the head of the Lane Theological Seminary. Henry spent three years at Lane studying popular speakers and developing his own preaching style. This preparation helped him become minister of the First Presbyterian Church in Lawrenceburg, Indiana, in 1837, and two years later, the pastor at the Second Presbyterian Church in Indianapolis. Henry traveled for weeks at a time on horseback preaching self-reliance, self-control—and garnering a reputation for delivering dynamic and emphatic sermons that appealed both to the principles of the common man and the values of the Victorian middle-class.

In 1847, when a group of wealthy merchants persuaded Henry to accept a position as first minister of the Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn, New York, he saw it as a way to meet his wife’s desire to move back East, as well as increase the size of his audience and prominence of his message. That message took on increasingly political tones as Beecher began using his pulpit more frequently to address social concerns. The issues of temperance and women’s suffrage were topics of great importance to Beecher and his sister Harriet, with whom he maintained a close relationship, but perhaps no issue stirred Henry more than his desire to see slavery abolished.

Beecher Speaks Out Against Slavery

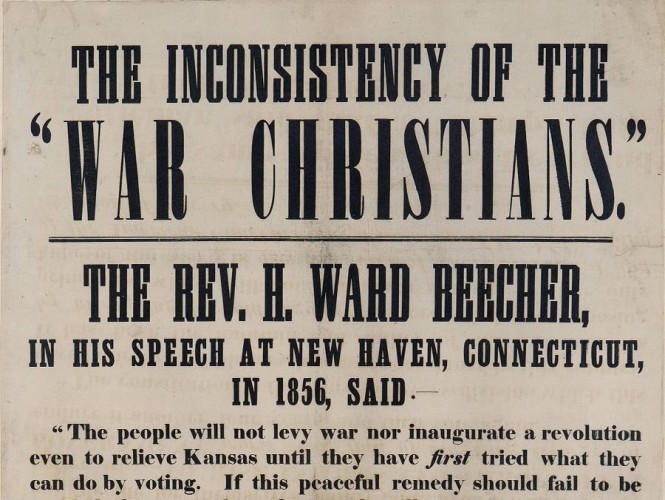

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska and allowed voters to decide whether they wanted to make slavery legal or illegal in Kansas, spurred Beecher to new heights of political activism. He launched himself into a series of speaking engagements and fundraisers to rally northern support against the violence and corruption of slavery. Beecher was quoted as saying he would rather have “war redder than blood and fiercer than fire” than to appease pro-slavery interests. His commitment to the anti-slavery cause was recognized throughout the Civil War and the rifles purchased with the money he raised quickly became known as “Beecher’s Bibles.” Years later, when the Stars and Stripes were victoriously raised over Fort Sumter in South Carolina in 1865, Henry Ward Beecher delivered the ceremony’s most important address.

One of the benefits Beecher realized from his move back East was greater access to the New York publishing houses that played such a vital role in shaping American thought. Beecher’s writing ability led to his authoring numerous works on religion. He also worked as a periodical editor for the Christian Union, and one of the largest religious journals of its day, The Independent. It was his affiliation with The Independent that led to one of the great American scandals of the 19th century.

The Shadow of Scandal

In 1872, a feminist named Victoria Woodhull published a story that accused Beecher of having an extramarital affair with Elizabeth Tilton, wife of Theodore Tilton of The Independent, and a friend of Beecher’s. The accusation first came about in a confession from Elizabeth Tilton to her husband in 1870. Despite Plymouth Church’s board of inquiry finding Beecher innocent of the charges, Theodore Tilton filed suit against Beecher for adultery in 1875 – a charge made more troubling by Mr. Tilton’s excommunication from the Plymouth Church in 1873. For six months the trial drew huge national attention, but after reviewing all of the testimony, including numerous contradictory statements made by Elizabeth Tilton, the jury was unable to come to a decision regarding Beecher’s guilt.

Illustration of the testimony in the great Beecher-Tilton scandal case – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Despite the negative publicity from the Tilton affair, people’s fears of corruption and fraud running rampant through government helped Beecher maintain his public speaking career. His message of morality and social progress was extremely popular with the American public. He maintained an extensive lecturing schedule throughout his later years, which left him little time for writing or for his family. In 1887 Beecher eventually accepted an offer to write an autobiography. Unfortunately, before work could begin in earnest, Henry suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died on March 8, 1887. The city of Brooklyn declared a day of mourning during which Beecher, survived by his wife and four of their nine children, was recognized as having been one of the most renowned public figures in the United States. While his body lay in state in Plymouth Church, over 40,000 people filed by to pay their respects. As historian William G. McLoughlin summarized, “Beecher was more than a popular preacher; he was a national institution.”

Gregg Mangan is an author and historian who holds a PhD in public history from Arizona State University.