By Sharon L. Cohen

From before emancipation and the 13th Amendment, Josephine Sophia (White) Griffing of Hebron, Connecticut, was an ardent advocate for enslaved and free people. Post-emancipation, African Americans faced pervasive racism and discrimination as many formerly enslaved people worked to build new lives. As an abolitionist and suffragist, Griffing’s work with the Underground Railroad, the Women’s Loyal National League, the National Freedman’s Relief Association of the District of Columbia, and the Freedmen’s Bureau helped thousands of African Americans access needed resources.

Supporting Freed People

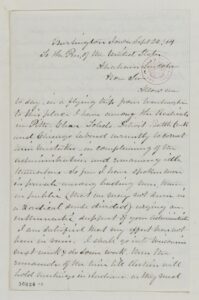

Letter from Josephine Sophia (White) Griffing to President Abraham Lincoln, September 24, 1864 on the topic of freedmen – Library of Congress

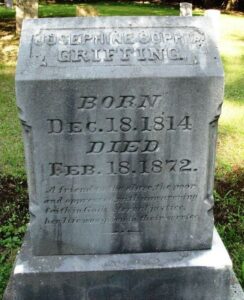

Born in Hebron, Connecticut, in 1814 and raised by parents who promoted education and personal independence, Josephine Sophia White became deeply involved in the abolition and women’s rights movements by young adulthood. She later married Charles Stockman Spooner Griffing and moved to Litchfield, Ohio—formerly part of Connecticut’s Western Reserve and a center of social reform. Involved with the Underground Railroad, Griffing, like many reformers, believed that the challenges facing African Americans did not end with emancipation.

Even before the Civil War, a number of Northern female abolitionists formed aid societies to educate and provide personal support to formerly enslaved people. These organizations grew in importance after President Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, which freed enslaved people in all seceded states. Griffing became heavily involved in the Women’s Loyal National League, an organization formed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony to petition for a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery.

Women working with aid societies often encountered opposition because of the widespread belief that it was unbecoming for women to work in public positions. Griffing found this unacceptable and petitioned the US Congress to allow women “to share more fully in the responsibility laid upon the government and the men of the North in the care and education of these Freedmen.” She then moved to Washington, DC, to focus on expanding her efforts. (During the war period, tens of thousands of African Americans came to the capital to seek support—many were children, women, elderly, and disabled.)

In 1864, the National Freedman’s Relief Association of the District of Columbia—a private entity largely concerned with providing thousands of recently freed people with food, shelter, and clothing—hired Griffing as a paid agent. She also ran two industrial schools to teach freedwomen professional skills such as sewing. Working closely with female volunteers at other community organizations and churches, Griffing also hoped to promote the suffrage movement.

Work with the Freedmen’s Bureau

Freedman’s Village in Arlington, Virginia in the suburbs of Washington, DC – Wikimedia Commons, Library of Congress

A year later, Congress passed “An Act to establish a Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands,” creating the Freedmen’s Bureau. As part of the War Department, the Freedmen’s Bureau supplied relief to displaced Southerners, mostly emancipated African Americans. In addition to providing such necessities as food and clothing, the bureau helped freed people establish schools, locate family members, legalize marriages, contract with plantation owners, and purchase land.

Once established, the Freedmen’s Bureau appointed Griffing to the position of Assistant to the Assistant Commissioner for the District of Columbia. In this role, she published an “Appeal on Behalf of the Freedmen of Washington, D.C.,” noting how several families frequently shared a single dilapidated room for “eating, sleeping, propagating, and dying.” Griffing also raised funds to help set up new benevolent organizations and ran two technical schools for women, a daycare, an employment office, and a counseling center.

Griffing’s efforts and ideologies, however, often conflicted with those in power, including US Representative Horace Greeley, who supported “self-reliance” over direct aid or “freely offered assistance” as the most beneficial means of helping the recently emancipated. The Freedmen’s Bureau fired Griffing from her position but she returned as a Capitol Hill and Navy Yard agent. She also joined other women who were establishing longstanding educational and social institutions to bring about lasting change.

The Freedmen’s Bureau was supposed to close a year after the Civil War ended, but both the US House and Senate overrode a veto by President Andrew Johnson and continued funding the agency. Despite the continued need for support against African American discrimination, Congress finally dismantled the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1872 (due largely to a lack of funding as well as Southern white opposition).

During her time in Washington, DC, Griffing resettled approximately 7,500 freed people on vacant land in the Western and Northern states, believing in the importance of property ownership for securing a better future. Upon her death from tuberculosis in 1872, her body was returned to Hebron’s Burrows Hill Cemetery.

Sharon L. Cohen is a communication specialist and professional writer who has authored several books on business and Connecticut history.