By Karen Frederick and Anne Young

In the years after World War I broke out in Europe, Greenwich, like the rest of the United States, faced the menace of two highly contagious and potentially deadly diseases: polio and Spanish Influenza. In both epidemics schools and theaters were closed, gatherings and rallies were cancelled, large congregations of people were to be avoided, and house-to-house visitations by nurses were undertaken. Newspapers were a primary source of the latest information, and the Greenwich Board of Health provided the first line of defense in preventing the unchecked spread of the contagions.

1916: The Polio Epidemic

In the summer of 1916, the first polio epidemic hit the United States. A viral illness, Polio in its most severe form causes paralysis, breathing difficulties, and death. In 1916, doctors were unable to treat or prevent it, causing a rising fear, uncertainty, and desperation. The disease spread from New York City up the East coast.

In July there were no reported cases in Greenwich. One month later eight cases had been reported and by October there were 44 cases and six deaths. All cases were taken to the Contagious Ward of the Greenwich General Hospital where they were quarantined for eight weeks. People exposed were quarantined in their homes for two weeks; an officer was stationed to see that the quarantine was observed. This epidemic returned every summer until the Salk vaccine was successfully field tested in 1952.

1918: Spanish Influenza

In 1918 Spanish influenza, a major disaster in world history, hit Greenwich. The first notice appeared in The Greenwich News and Graphic on September 20, 1918: “Health Dep’t Warns Against Spanish Influenza.” On October 2, Charles Hess became the first victim. The epidemic ran its course over eight weeks. In all, 1,629 cases were reported with 98 deaths. While Greenwich found the number of deaths high, around the globe more people would die from this epidemic than the 16 million soldiers who died in World War I.

Greenwich Board of Health

Dr. Alvin W. Klein, head of the Greenwich Board of Health, realized that a contagious germ, in the end, is more dangerous than a burglar and more costly than a fire. He initiated processes to keep the residents of Greenwich safe—especially from deathly epidemics—by instituting polices that affected all town residents.

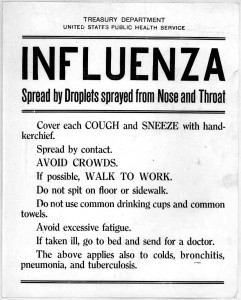

During the polio epidemic, new people coming into Greenwich were inspected, and, if necessary, kept under observation; pamphlets in three languages were distributed explaining principles of hygiene required for prevention. Unlike polio, which lacked a cure, an influenza vaccine was available. Although only partially successful, all children in public, parochial, and private schools were vaccinated as a precaution. People were asked to wear face masks, to carefully dispose of handkerchiefs, to not spit in public places, and, finally, “be fair to others.”

Karen Frederick, Curator and Exhibitions Coordinator, and Anne Young, former Curator of Library and Archives, of the Greenwich Historical Society contributed this article and co-curated the exhibition Everyday Heroes: Greenwich First Responders (September 14 through August 26, 2012) from which it is derived.