by Walter W. Woodward for Connecticut Explored

After American independence, Connecticut, like many Northern states, examined whether slavery was compatible with American ideals. It decided, in a half-hearted way, that it was not. Connecticut chose to emancipate its enslaved people, but, concerned about the property rights of owners did so very gradually. In 1784, the state passed legislation freeing any child born to an enslaved woman after March 1, 1784, but not until that child reached the age of 25. It did nothing to free either the child’s father or mother. Later, laws were passed lowering the age of emancipation and forbidding the sale of any slaves out of state (where emancipation laws could be circumvented), but slavery continued here well into the 19th century.

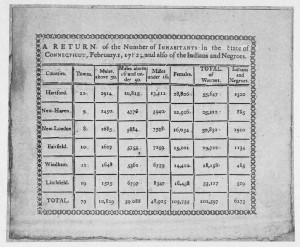

A return of the number of inhabitants in the State of Connecticut, 1782 – Library of Congress, American Memory

Supported by vocal abolitionists such as Jonathan Edwards Jr. and Theodore Dwight, many Connecticut masters freed their slaves well before the emancipation laws required. By 1800, there were more than 5,000 free blacks in Connecticut. Other Connecticans, however, including such prominent people as Noah Webster and the jurist Zephaniah Swift, felt such moves were ill advised. They believed gradual emancipation was important for both public safety and the welfare of the enslaved. Connecticut’s blacks—both free and enslaved—not surprisingly thought otherwise, and they were a steady voice urging faster emancipation. In the end, slavery remained in the Land of Steady Habits until 1848, though the number of enslaved people dropped to 97 by 1820 and 17 by 1840, according to US Census data.

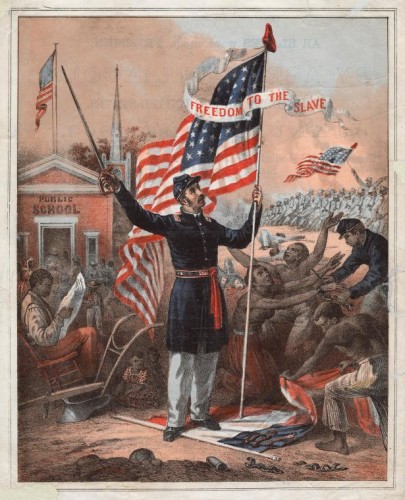

Opposing slavery was never the same as advocating equality, and here in the state William Lloyd Garrison called “the Georgia of the North,” racism remained deeply entrenched long after slavery ended. Views on Civil War emancipation were mixed: While Connecticut Republican Governor William Buckingham personally traveled to Washington to urge President Lincoln to emancipate enslaved people months before Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, other political leaders protested vigorously that the war was only being fought to save the Union, not to end slavery. After the Emancipation Proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863, Connecticut’s State Democratic Convention adopted a resolution saying the Proclamation, as reported in the February 21, 1863, issue of the Columbian Register, “would disgrace our country in the eyes of the civilized world, and carry lust, rapine, and murder into every household of the slaveholding states.”

A similar popular racist response met the 1865 passage of the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery nationally. When the Republican-dominated Connecticut General Assembly sent voters an amendment to the state constitution removing the word “white” from the description of who could vote in state elections, the electorate soundly rejected it, maintaining political inequality as state policy.

It is hard for many of us to conceive that the 15th Amendment guaranteeing blacks the right to vote was subsequently passed as much to address the actions of states like Connecticut as to address such actions in the South.

While the Civil War that ended slavery did indeed pit the North against the South, it is sobering to recall that our nation remained united by deeply embedded racism for at least another century.

Walter Woodward is the Connecticut State Historian

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 11/ No. 1, WINTER 2012/2013.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.