By Rena Tobey

Better known today than in his lifetime, African American artist Ellis Ruley, and his astonishing story, are an integral part of Norwich’s history. After working in the town’s industrial economy, Ruley’s narrative swerved dramatically during the Great Depression. That story bucked and pulled on Norwich’s social mores, resulting in tragedy. More questions than answers puncture the account, just as the artist leaves behind enigmatic, enchanting paintings.

In 1882, Ruley was the first child born to a couple marked by slavery. His father, Joshua Ruley, fled Wilmington, Delaware, aboard a coal boat headed north. Family legend relays that Joshua swam up the Thames River and became the first runaway slave to live in Norwich. Eudora Robinson, Ruley’s mother, brought five children and an enslaved heritage to her marriage. Together, the couple had seven children, forming a large family, that like other Norwich blacks, lived in poverty.

The town prospered as a convenient rail stop between Boston and New York City, until 1889, when the new rail bridge over the Thames River at New London bypassed Norwich. The Ruley family’s struggles mirrored the town’s subsequent decline. Ellis Ruley left school early, to shovel coal on barges and work as a mason tender for construction. Ruley worked as a day laborer until 1949, when he retired to paint fulltime.

Turmoil and Racial Tension

Turmoil defined the artist’s life. At least eight miscarriages and stillborn infants marred his marriage to Ida Bee, before the birth of his daughter Marion in 1912. The couple separated, and Ida Bee died before Marion turned four. Nearly 20 years later, Ruley married Wilhelmina Fox, a German, white woman, after she divorced Ruley’s brother Amos. Forming an interracial couple was audacious during this time, especially considering the presence of the Ku Klux Klan in Norwich for more than a decade. The organization’s first cross burning there was in 1924, and the KKK found a foothold among Norwich residents embittered by the influx of eastern European, predominantly Polish, immigrants.

Bronze portrait of Ellis Ruley by his biographer, Genn Palmedo-Smith (gift of the artist) – Courtesy and collection of the Slater Memorial Museum

A sudden influx of wealth most likely added to the resentment of the mixed-race marriage. In September 1929, Ruley received injuries in a truck accident while leaving a construction site. Three years later, a court awarded him $25,000 in damages—a small fortune during the height of the Depression. Ruley promptly bought property on Foxhill in all-white Laurel Hill. A dilapidated, 1700s farmhouse, with no electricity or running water, remained on the property. The Ruley family promptly moved in, perhaps carried by the brand new, green Chevrolet coupé they nicknamed “Green Hornet.” When many families faced desperate times, the Ruley’s owned a new car, a home, and property in an established neighborhood.

Ruley went to work renovating the house, reportedly only 18 x 20 feet, to create a sanctuary. He had a drive for self-sufficiency, and the vegetarian family, a rarity at the time, grew vegetables and tended a fruit orchard. They also foraged the property’s hemlock forest for herbs to use in medicinal salves. Around 1939, at age 57, Ruley began to create—first decorating window screens he built for the house. Neighbors then paid him to paint their window screens. One often saw paintings of animals, birds, and tropical plants on black masonry paper hung around the Ruley home.

Still, the neighborhood proved less than congenial. His children and grandchildren were taunted by name calling and stone throwing on their way to school. Drunken troublemakers catcalled during the night. Wilhelmina grew increasingly frustrated, even as she implored her family to ignore them—she ultimately left Ruley shortly before his death. As Ruley stabilized the long, wagon-road driveway up the hill to his house, white neighbors began to use it without his permission. Disputes arose and locals pressured Ruley to sell his property, but he refused, and instead built stone walls along the property line.

Ellis Ruley Finds His Escape in Art

Art became his retreat. He began painting on posterboard and Masonite, using oil-based house paint and varnish he bought at the hardware store. Ruley did not date his work, although he did have a stamp made reading “Ellis W. Ruley,” which he sometimes stamped twice per work. He set up his handmade easel at the window or in the yard to depict nature in balanced harmony with humans and animals.

Ellis Ruley, Adam and Eve, house paint on card table top, circa 1940s – Courtesy by permission of author, Glenn Palmedo-Smith, Discovering Ellis Ruley, Crown Publishing

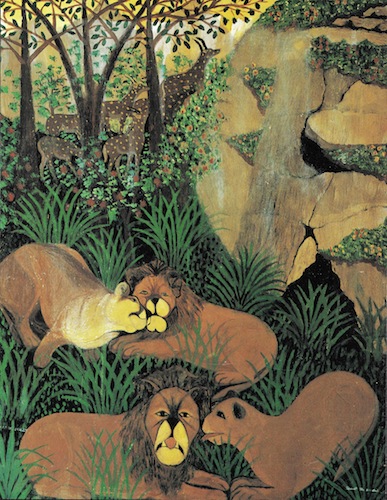

Dreamy, evocative, and poetic, Ruley’s paintings often expressed biblical and African folkloric themes in his distinctive, self-taught style. His most acclaimed painting, and the largest, portrays a white-skinned self-portrait as Adam with a white Eve, before the serpent’s temptation. Ruley believed the races could live together in peace, and he lived in his own Garden of Eden on Foxhill. The Slater Museum owns Daydreaming, another metaphorical piece. Here, lions relax in an idyllic garden setting, loving and nuzzling each other. Some interpret the lion couple at the front as representing Ruley and Wilhelmina. Antelope feel safe lingering in the scene’s background. Ruley painted the potentially ferocious animal kingdom as gentle togetherness.

Ellis Ruley, Daydreaming, Landscape with Lions, enamel house paint on cardboard – The Slater Memorial Museum

The Slater played a pivotal role in ensuring Ruley’s memory today. Joseph Gualtieri, its former director who died in late January 2015, met the artist in the early 1950s. Gualtieri taught painting and drawing at the Norwich Free Academy, and when the newly retired Ruley introduced the director to his work, Gualtieri invited the painter to be part of the school’s art fair in December 1952—Ruley’s only exhibit during his lifetime. Gualtieiri also tried to promote Ruley’s work in New York, but meeting with failure, reported that the timing was “off” for the black folk artist’s work.

Collector Glenn Robert Smith met the director when researching Ruley and quotes Gualtieri, “Due to his lack of training, all his paintings took on an unmistakable Ellis Ruley look–a primitive quality, possessing great charm, always colorful, decorative, and festive in mood, a celebration of life.” Smith found Adam and Eve at the Brimfield Antiques Fair in 1984, paying $3,500 for an unsigned work by an unfamiliar artist. (Fifteen dollars was the most Ruley charged for a painting.) Gualtieri authenticated Adam and Eve, remembering it hung over Ruley’s couch at home.

Smith’s efforts and a posthumous exhibit brought renewed attention to Ruley’s work. His fanciful take on media imagery attracted collectors. Ruley freely borrowed depictions of white men and women from movie stills and magazine ads for his quirky paintings of cowboys on rearing horses and scenes of everyday Norwich life. His nostalgic town images included the tramway, rental canoes at Monhegan Park, and the nearby falls. Ruley loved the exotic and painted zebras, literally showing black and white working together. He painted Grey Owl, who left England and his identity as Archibald Belaney, to experience indigenous life in Canada.

Women also made a beloved subject. The Amistad Foundation’s African American Collection at The Wadsworth Atheneum features Grapefruit Picking Time, showing Ruley’s love of repeat patterning. The strong vertical of the ladder interrupts the flattened fruit orchard. Each woman, rung by rung, has a distinctive attitude toward the painter, and the viewer, beseeching, miffed, playful.

Untimely and Suspicious Deaths

But all was not beautiful in Ruley’s world. In 1948, Douglas Harris, married to Ruley’s daughter Marion, was found with three skull fractures, thrust head first in the property’s well. The coroner determined that Harris tripped and fell into the well. Then in January 1959, the 77-year-old Ruley cashed his Social Security check, visited a favorite downtown bar, and afterward, stepped out of a taxi near the front door of his home.

The next morning, Ruley lay partially frozen, face down in a long trail of blood, 200 feet down his driveway, with his empty wallet nearby. As with his son-in-law, authorities declared the death accidental, attributed to a heart attack. Weeks later, the house burned, destroying about 50 paintings. Devastated, Marion was institutionalized at Norwich State Hospital and had a lobotomy without the family’s consent. Witnesses later reported seeing a city judge driving the Green Hornet. Norwich blacks believed Ruley murdered and that prominent officials played a part in the cover-up.

In October 2014, officials exhumed the bodies of Ruley and Harris at Maplewood Cemetery in Norwich for examination. The resulting autopsy for Ruley proved inconclusive, although the cause of death for Harris remained suspicious. Both bodies received new headstones and coffins upon reburial.

Rena Tobey is an American art historian, with special focus on women artists working before 1945. She also created a tabletop board game on the adventures of art and art history.