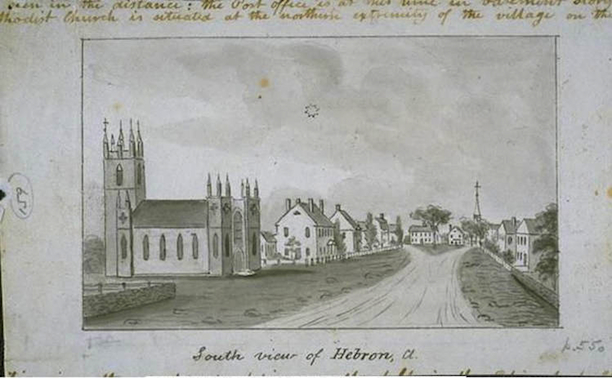

Cesar and Lowis Peters (whose names are often found spelled Caesar and Lois) were enslaved African Americans who lived in Hebron, Connecticut, in the late 18th century. While the story of how they survived as slaves contributes greatly to the underappreciated history of slavery in Connecticut, the story of how they gained their freedom reveals much about transformations in popular thinking about race, slavery, and liberty during the era of the American Revolution.

Cesar arrived in Hebron around 1758, when he was eight or nine years old. He was the slave of Mary Peters, the mother of the local missionary from the Anglican Church, the Reverend Samuel Peters. About ten years later, Mary transferred ownership of Cesar to Samuel. It was during this period that Cesar married a slave named Lowis.

Cesar and Lowis Peters Succeed on Their Own

Peters House in Hebron, 2024 – By John Phelan, Wikipedia. Used through a CC BY 4.0 license.

In September 1774, Samuel Peters fled Hebron because his Anglicanism in Congregationalist Connecticut and his loyalty to the British crown alienated him from the community and jeopardized his security. He eventually moved to London, England. In the months after Peters’s flight, Cesar and Lowis and their growing family continued to live and work on Peters’s large estate.

With the American Revolution well underway in 1776, however, the newly created state’s attorney of Connecticut confiscated Samuel Peters’s property as abandoned and converted it to public property to be used for the support of the state. Officials summarily turned out Cesar and Lowis from Peters’s land and rented the farm to white tenants. Despite Cesar’s skillful operation of the farm, no members of white Hebron intervened to protect Cesar and secure his tenancy. Cesar and Lowis thus found themselves abandoned at a time of enormous insecurity, yet the captive couple’s resourcefulness during this period impressed many residents.

Cesar’s family squatted on marginal lands immediately adjacent to the Peters estate. Townspeople soon began marveling at how well the family supported themselves over the next five or six years, without assistance from a master or aid from the local population. With the war’s end, no one offered any opposition to Cesar, Lowis, and their several children re-occupying Peters’s estate after its white tenants left the property in a damaged and dilapidated state. Cesar set about mending fences and repairing buildings and returned the farm to its previously prosperous ways.

The Town of Hebron’s Showdown with Slave Traders

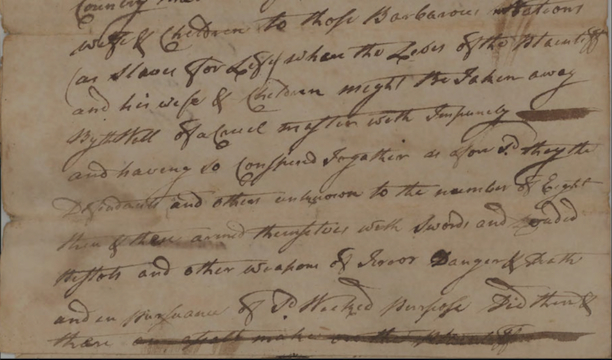

In September 1787, however, six heavily armed men approached the Peterses’ house. Two of them were appointed agents of Samuel Peters (who still lived in London); the other four were men from South Carolina intent on taking possession of Peters’s slaves, who now resided in the house. The agents looked to take Cesar and his family and sell them to cover some pressing debts.

After dismounting from their horses and their wagon, the men forcibly entered the house, grabbed Cesar, his wife, and their children, and dragged them to the wagon. When white neighbors approached the men and asked them for justification, the agents produced power of attorney documentation and a deed of sale. The six men, weapons brandished, then galloped away with their captives.

Detail from the court document Cesar Peters vs. John and Nathaniel Mann, November 14, 1789 – Connecticut State Library, State Archives. Used through Public Domain.

The townspeople of Hebron became incensed. A large posse of local men convened and quickly decided on a remarkable plan. Elijah Graves, a local tailor, filed a complaint claiming that Cesar and his family left town without paying for some clothing. After issuing a warrant for the family’s arrest, authorities quickly set out for Norwich in an attempt to overtake Cesar’s abductors. Catching up with them not long before they intended to load the family on to a ship bound for South Carolina, the constable presented the warrant for arrest, took Cesar and his family into custody, and promptly returned them to Hebron.

The night Cesar, Lowis, and their children returned to Hebron, the townspeople held a tremendous celebration at Roger Fuller’s tavern. Yet Cesar and Lowis were not completely out of danger. Despite their rescue, Samuel Peters’s agents continued to pursue opportunities to sell and disperse the family. A conviction on the theft charges and the subsequent sentencing to two years of service under the watchful eye of Cesar’s good friend Elijah Graves helped to thwart those attempts, however. In January 1789, after the state’s General Assembly reviewed a series of petitions and depositions filed to free Cesar and his family from slavery, the state finally emancipated them.

The family moved to Colchester and then Tolland, where Lowis died in 1793. After remarrying, Cesar moved to Coventry before returning to Hebron in 1803. He died there on the Fourth of July in 1814.