By Michael Sturges

Sister to two of the most famous figures of the 19th century–Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry Ward Beecher–Catharine Esther Beecher achieved fame in her own right as an educator, reformer, and writer.

The eldest child of the renowned Beecher clan, Catharine was born in East Hampton, New York, in 1800. When she was 10, her family moved to Litchfield, where she received her first formal education at Sarah Pierce’s Academy for Young Women. Beecher’s mother, Roxanna Foote Beecher, died in 1816 of tuberculosis, leaving 16-year-old Catharine to serve as a surrogate mother to her younger siblings, nearly all of whom went on to fame, including preacher and lecturer Henry Ward Beecher, suffragette Isabella Beecher Hooker, abolitionist Edward Beecher, and author and abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe.

It was during this time that Beecher became familiar with the responsibility and nobility of motherhood, which she would never experience through children of her own. She suffered the greatest tragedy of her life in her early 20s when her fiancé, Yale professor and mathematician Alexander Fisher, died in the shipwreck of the Albion off the coast of Ireland in 1822. Devastated, Beecher vowed to stay true to Fisher’s memory. She never married and relied on the strength of her younger siblings to cope with the loss.

Hartford Female Seminary, 1856

Founder of Schools for Women

Beecher’s early career was devoted to promoting education for women and the evolution of education as a profession. After Fisher’s death, Beecher and her sister Isabella founded a school for young women in Hartford, which in 1824 became the Hartford Female Seminary. By the time Catharine followed her father, the famous preacher Lyman Beecher, West to Ohio in 1831, the seminary had become one of the premier women’s schools in the United States

In Cincinnati, she founded another women’s school, the Western Female Institute, but this endeavor was short lived due to the lack of financial support resulting from the Panic of 1837, an economic depression that gripped the nation. During the 1840s, Catharine worked to recruit teachers for schools on the western frontier and founded the Central Committee for Promoting National Education. This organization ultimately promoted teacher education and contributed to the establishment of education as a profession. In 1852 Catharine Beecher was one of the founders of the American Women’s Educational Association, which planted higher learning institutions for women in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Iowa.

As Beecher aged, her advocacy found additional outlets in writing and lecturing. She authored The Moral Instructor for Schools and Families: Containing Lessons on the Duties of Life (1838), A Treatise on Domestic Economy for the Use of Young Ladies at Home and at School (1842), and Educational Reminiscences and Suggestions (1874). Through these works one can see the development of Beecher’s philosophy of education and gender relations.

Equality in the Domestic Sphere

Beecher was one of the principal proponents of the 19th-century “cult of domesticity.” She shared the widespread Victorian idea that a woman’s sphere of influence was the home. There, women would undertake tasks related to nurturing children and caring for the family’s environs. Beecher combined this belief with a feminism engendered in her through her early education under Sarah Pierce.

According to Beecher, men and women were equal, but she did not seek to meld the spheres of men and women. Her approach to feminism was to elevate the feminine realm to the same importance and professionalism of the male one. If women belonged in the home and men in the world, then women should receive an education in child rearing, home economics, and domestic concerns that was as rigorous and valuable as that which men received in law, medicine, or business.

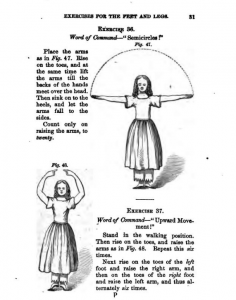

Physiology and calisthenics. For schools and families by Catharine E. Beecher

Through her writings and the schools she founded, Beecher advocated that women be taught history, Latin, rhetoric, algebra, logic, physical education, and natural philosophy—this at a time when women who received an education were most often taught etiquette, literature, and modern languages. Beecher also pioneered education in what she referred to as “domestics,” which would today be considered family and consumer sciences.

Beecher’s diverse educational work shared a common thread: that women, who would become wives and mothers, were responsible for the preservation of public health. “They are agents in accomplishing the greatest work that ever was committed to human responsibility,” she wrote in her much-reprinted volume Treatise on Domestic Economy for the Use of Young Ladies at Home and at School.

This belief in preparing women to be respected professional caregivers also found an outlet in Beecher’s efforts to equip women to become teachers, a profession which Beecher saw as naturally suited to women. Thus, Beecher became a co-pioneer of American Public Education with Horace Mann of the Common School movement, which advocated the provision of a basic education for children of every social class. Her advocacy for female teachers coincided with the growth of Normal Schools (institutions that taught the standards or norms necessary to undertake the profession of teaching). Beecher’s lasting influence on American public education was to make the role of public school teacher a predominantly female one.

Opposition to Women’s Suffrage

Later in life, Catharine Beecher wrote more frequently about women’s suffrage. Her reputation as an advocate for women’s education, as well as the suffrage work of her younger sisters, makes her position on securing the vote for women surprising to modern observers. She firmly opposed women’s suffrage, an opinion which created tension with her sisters.

“American women would regard the gift of the ballot not as a privilege conferred but as an act of oppression, forcing them to assume the responsibilities of a man, for which they are not, and can not, be qualified,” Beecher wrote in her book An Address on Female Suffrage (1870). She believed politics could only interfere with or distract women from their far more important task of maintaining the moral fabric of the United States and that mixing the spheres of men and women would weaken both.

Catharine Beecher died in Elmira, New York, in 1878. Like the Beecher she was, she had spent her life promoting change. To Catharine—who as a young woman had overseen a household that produced extraordinary social crusaders—the work of creating an intellectually stimulating, secure, and moral environment in the home or classroom was the highest calling to which anyone, man or woman, could aspire.

Michael Sturges is a social studies teacher at Nonnewaug High School in Woodbury, Connecticut, and a graduate student at Central Connecticut State University.