By Peter Vermilyea

Litchfield’s borough of Milton, located in the northern part of town, derives its name from the several small mills located there along the Shepaug River. One of those mills was the corn mill of brothers Benjamin and Oliver Dickinson. Oliver was a master carpenter who counted among his constructions the Trinity Episcopal Church in Milton. Around 1778, Oliver married Anna Landon, and their son Anson was born in 1779.

When Anson was 17, he became the apprentice of Isaac Thompson, a Litchfield silversmith. Of his apprenticeship, it was written:

He was frequently observed to steal away to a retired chamber and spend hours of solitude, intent upon some deep and self-imposed task. Some of the family finally discovered that he had been intently engaged in painting.

Dickinson’s work was evidently of such beauty that he was released from the terms of his apprenticeship, and he embarked on a career as a painter of miniatures, watercolor portraits painted on small pieces of ivory that could be set in jewelry, carried in a pocket, or framed and displayed.

Well-To-Do Clients from Litchfield to Quebec

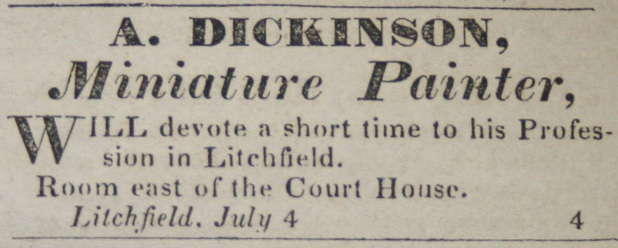

In 1802, the following advertisement appeared in the Connecticut Journal:

Anson Dickinson has taken a room directly opposite the Episcopal Church, he offers his services to the Ladies and Gentlemen of New Haven, in the line of MINIATURE PAINTING.

Anson Dickinson advertisement – Litchfield Historical Society

The earliest known portrait by Dickinson is of his uncle, Abel Dickinson, which was painted on New Year’s Day, 1803, and is signed by the artist on the reverse side. Litchfield, with several well-to-do residents and the students of the Sarah Pierce Academy and Tapping Reeve Law School, provided a steady source of commissions when Dickinson’s practice was starting out.

A particular challenge for all miniaturists of the period was obtaining the necessary equipment for the craft. In addition to the pigments that would be ground and combined with gum arabic, a binding agent, and glycerin, for the right paint consistency, Dickinson required magnifying and reducing glasses. The reducing glass was used to secure the correct proportion for his subject, and the magnifying glass allowed for the fine detail work in his paintings. Both of these required stands so that the artist’s hands were free to paint.

Elizabeth Canfield Tallmadge, painted by Anson Dickinson – Litchfield Historical Society

Soon, Dickinson exhausted the potential commissions of Litchfield and embarked on a being an itinerant artist. He traveled to New York, Albany, Montreal, and even Charleston, South Carolina, between 1805 and 1812. In 1812, Dickinson married Sarah Brown of New York City. The couple settled there and in 1824 adopted two children.

Dickinson would spend the next eight years operating a New York studio and became so well established that he no longer needed to seek out commissions. During this period, he painted almost 300 portraits, including some of the most famous residents of the city.

Financial Panic of 1819 Derails Dickinson’s Career

In 1819, however, financial panic struck the city and the country; Dickinson relocated his operations to Montreal and Quebec and in 1822 moved to Boston. A few years later, he had relocated to Washington, DC. He was unable, however, to rediscover the success he enjoyed before the panic and returned to Connecticut in the early 1830s.

Marker for the site of the Dickinson home, along Sawmill Road in Milton, Litchfield – Peter Vermilyea

Dickinson died in Milton on March 9, 1852, at the age of 73. He had spent over 40 years traveling the United States and Canada to execute what many considered to be the finest American portrait miniatures. His tally of portraits exceeded 1,500, an average of about one a week over the length of his career. Celebrated in his own time, Dickinson has been largely forgotten in ours. His works, however, grace the collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Peter Vermilyea, who teaches history at Housatonic Valley Regional High School in Falls Village, Connecticut, and at Western Connecticut State University, maintains the Hidden in Plain Sight blog and is the author of Hidden History of Litchfield County (History Press, 2014).

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.