By Elizabeth Correia

Amy Johnson was a Mohegan woman who began her life caught in the undertow of an ever-expanding white settler society. She spent five years at a missionary school and working for colonists before finally making a home in Waterford, resisting the life new settlers wanted her to live.

Colonial Education at Moor’s Indian Charity School

Amy Johnson was born in 1748 to a prominent Mohegan family but found every phase of her life disrupted by colonialism. She was born within detrimentally restricted tribal land, her parents baptized her as a Christian, and at 10 years old Amy’s father died while serving the British in the French and Indian War. At 13 she was taken to Moor’s Indian Charity School in what was then Lebanon Crank, Connecticut.

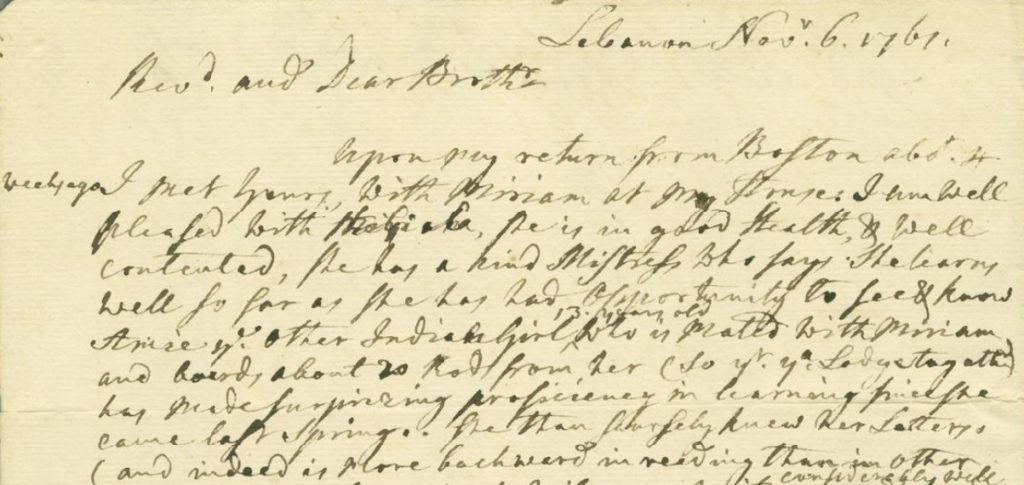

Congregational Minister Eleazar Wheelock founded Moor’s Indian Charity School in 1754 to convert Algonquian boys into missionaries. Amy Johnson was one of the first girls taken to Moor’s Charity School (in 1761) to learn English housewifery until Wheelock could marry her and others off to Natives trained as missionaries. The girls worked in white households, washing, cooking, sewing, spinning yarn, tending to farm animals, and bending to the whim of the homeowners. Wheelock sent Johnson to David Bull’s residence. This position was particularly demanding since Bull operated his home as the “Bunch of Grapes,” downtown Hartford’s busiest tavern.

Once a week, female students at Moor’s School learned basic reading and writing in Wheelock’s home. Sundays they spent in church, sitting behind white women while absorbing Calvinist scripture. Johnson’s educators attempted to teach her that her old mannerisms, clothing, hair, language, and way of thinking were punishable in the eyes of God. While being taught the Christian moral code, she lived surrounded by colonists who acted in opposition to that very code by abusing her and her people. This dichotomy tormented many Native students of Moor’s Indian Charity School, some of whom either ran away or dulled their pain through alcohol consumption.

In 1765 Johnson was 17 years old and expected to marry the Montauk missionary David Fowler, who had been a student at Moor’s. Fowler planned to take Amy with him to work among the Oneida until he discovered that she had consumption. Fowler wrote to Wheelock, disappointed, “I thought I found one that was able to go through hard Work: but I see now I am in the same Difficulty as before.” There is also evidence in Fowler’s letter that Johnson refused him, as Fowler writes, “She tells me that she is quite contented here and hopes to tarry all Summer,” even though Fowler needed to leave that year.

A Return to Mohegan Life

A 1768 Dutch map marking the Mohegan village as “Indi sches dorf.” – University of Connecticut Libraries, Map and Geographic Information Center (MAGIC)

In 1766 Amy Johnson returned to her family in Mohegan, now Montville, where she recovered from her illness. In the Mohegan village Johnson likely learned traditional crafts (such as basketmaking) that were adapted to make a profit in English markets while still allowing women to sustain their cultural identity. Johnson married Joseph Cuish, a Western Niantic man whose father was a Baptist minister among the Mohegan. Amy and Joseph had at least two children and they lived in Waterford on several acres Joseph purchased from white settlers.

By now Amy Johnson had devised a way to survive in the growingly white colonist world in Connecticut without becoming estranged from her tribe. Despite the attempts of colonists to convince her of the inferiority of Native American life, she, like many others, resisted assimilation and contributed to the survival of Mohegan culture. Letters written by Eleazar Wheelock demonstrate that he keenly felt this collective resistance: “While I am wearing my Life out to do good to the poor Indians, they themselves have no more Desire to help forward the great Design of their Happiness…pulling the other way and as fast as they can undoing all I have done.” Wheelock’s words reinforce the legacy of Amy Johnson and other Mohegan women who persisted. While forced to live among invading settlers, Johnson pulled the other way and avoided becoming a missionary wife. Instead, she rejoined her community and instilled in her children the knowledge and morals she and her own culture deemed valuable.

Elizabeth Correia holds an MA degree in Public History from Central Connecticut State University and works in cultural resource management.