By Nicole Fontaine

The Waterbury Clock Company experienced an increased demand for watches after the First World War, and to turn a profit, they hired women at low wages to work seven days a week. The company called for women with “nimble fingers” to paint the dials and numbers onto watches in assembly-line fashion. To speed up the process, women would “lip-dip,” meaning that they placed the paintbrush into their mouths and then dipped the brush into the radium-laced paint. Repeating this process caused the radium to linger in their mouths. Initially, the women did not know the risks of radium and even enjoyed painting it onto their nails and clothing to glow in the dark, but exposure to radium later led to over 30 deaths in the company.

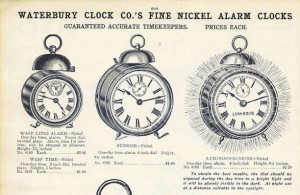

Detail of an advertisement for Waterbury Clock Co.’s Luminous-Sunrise, a part of the Nickel Alarm Clock line

Frances Splettstocher, a woman in her early twenties, was the first to die in the Waterbury Radium Girls tragedy. She suffered the common symptoms and ailments of radium poisoning, such as: anemia, sore throat, deteriorating jaw, soft teeth, spontaneous bone fractures, and aches. Although Waterbury Clock Company officials were beginning to understand the effects of radium on their workers, they rejected the company’s connection to Splettstocher’s death (but discouraged lip-dipping after 1925). Just four years later, twenty-two-year-old Mildred Cardow died from working with radium at the Waterbury Clock Company. The following year, Mary Damulis, also in her early twenties, died due to lip-dipping. This finally motivated the Waterbury Clock Company to forcefully denounce lip-dipping in their factory.

After 1926 it became evident that radium at the Waterbury Clock Company caused illnesses and deaths among their workers. Between 1926 and 1936, the company issued over $90,000 in medical settlements. Due to these expenses, the company decided to change its qualifications for worker’s compensation. In 1927, a woman now had only three years to file a claim, rather than the typical five. This change did not affect some of the women, however, because their symptoms became evident in a very rapid fashion. But most of the women did not see the effects of lip-dipping until long after the five year requirement, when they developed cancer. This did not only affect workers in Waterbury, but also Illinois and New Jersey, where both states lost 30 to 40 women due to lip-dipping. In 1941, the Waterbury Clock Company decided to address some of their employees’ concerns, and due to the risks employees faced on the job, the company agreed with the union to increase wages by two cents.

An article from the Pittsburgh Press, December 30, 1931, describing the death of Edith Lapiano, 25, a victim of radium poisoning

Painful Lessons Learned

The tragic story of the Waterbury Radium Girls helped build a nation. As World War II approached, the women were essentially test subjects to the repercussions of radium exposure. According to the US Atomic Bomb Commission: “If it hadn’t been for those dial painters thousands of workers might well have been, and might still be, in great danger.” These young women, those who died and those who led long, painful lives, helped aid US forces in World War II.

The last Waterbury Radium Girl, Mae Keane, passed away at the age of 107 in March of 2014. She credited her long life to her love for laziness and eventually being placed in a different position at the Waterbury Clock Company. She worked as a dial painter for only a few months,but still lost all her teeth by the age of 30 and faced numerous battles with cancer.

The story of Waterbury’s Radium Girls provides unique insight into women’s history. The Waterbury Clock Company placed women into the role of “dial painters” based on the belief that women had nimble fingers and did well at precision tasks. When employers learned of the deadly effects of radium, the company claimed to discourage lip-dipping, but actually relied on the use of the technique for its success. While many young women died of radium, many others lived longer lives, albeit often in extreme pain. Their tremendous sacrifices were not entirely in vain, however, as their experiences helped scientists better understand the horrifying effects of radium.

Nicole Fontaine is an undergraduate student at Central Connecticut State University pursuing a degree in History Secondary Education.

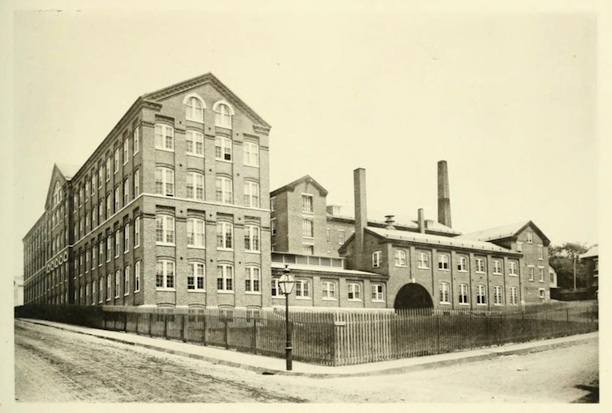

Waterbury Clock Company from Waterbury and her Industries: Fifty attractive and carefully selected views by Homer F. Bassett, 1889