By Steve Thornton

We might drive over the Bulkeley Bridge every day, but we seldom think about the sweat and toil it took to produce the link between Hartford and East Hartford. Even those who think they know the history of the bridge’s construction probably don’t know the story of the Black workers who risked their lives for low pay to create this century’s first permanent stone structure over the Connecticut River.

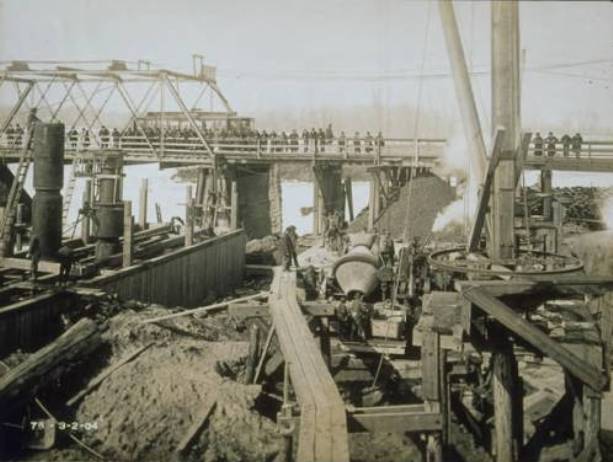

A wooden covered bridge spanned the Connecticut River at the Bulkeley site beginning in 1818. In 1895 the bridge burned down and it took eight years before an official report recommended that a new overpass should be built to take its place. In the meantime, temporary bridges and ferries linked the two towns. Bridge began construction in 1904; the span was completed three years later and dedicated in 1908. It was first called the Hartford Bridge and later named to commemorate Morgan Bulkeley, who, in addition to serving as Hartford’s mayor, Connecticut’s governor, and a US senator, had been the head of the Commission that oversaw the bridge’s construction.

Bulkeley Bridge Construction: Abutments and Temporary Iron Bridge, Hartford, 1906. 1967.96.6 – Connecticut Historical Society

Discrimination Factored into Job Pay and Risk

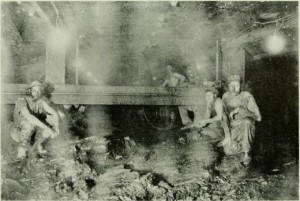

Digging the foundation of the bridge was the first order of business. This was the job of the sand hogs, as they were known. As bridges rose along the east coast, this dirty and dangerous work went first to Irish immigrants. But by the turn of the 20th century many of those sons of Erin had acquired skilled trade jobs. The work was passed on to Black workers, who occupied the lowest rung on the job ladder.

Although unions have existed for most skilled jobs almost since this country’s founding, common laborers were not invited into the guilds in the 19th or early 20th centuries. And Black workers, no matter what their skill, were seldom organized into unions. A few exceptions, such as the Knights of Labor and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), stand out in the early 1900s; they welcomed all workers.

The bridge’s foundation averaged 50 to 60 feet in depth. Enclosures, called caisson chambers, were built so that workers could work in a dry space and adapt to the change in atmospheric pressure as they descended beneath the water’s surface to dig. Without the ability to slowly acclimate to the differences in pressure, workers would get the “bends” (a condition known as decompression sickness that is caused when the body too quickly returns to the lower atmospheric pressure above water level). Iron pipes carried forced air from engines on shore, along the bridge’s footpath, and to the caissons. The work took place around the clock in 8-hour shifts but even the strongest sand hog could only work a few hours at a time under the river. Considering the difficulty of the work, sand hogs were only paid $2.50 a day.

“Sand Hogs.” Laborers at work in the caisson under the bed of the river (Hartford). From Crossing the Connecticut by George Edward Wright, 1908.

About 100 Black workers labored as sand hogs on the Bulkeley bridge. They were supposed to be paid every Monday at noon. But the contractor, McMullen, Weand and McDermott, had failed to meet the paycheck deadline on a number of occasions. Non-payment for work was so common around this period that the Connecticut General Assembly had passed a law requiring businesses to pay their workers on time or face penalties.

No Pay, No Work: The Sand Hogs Strike

One Monday in August, 1904, the sandhogs’ pay envelopes once again failed to appear. At 4:00 pm, most of the 40 workers on second shift refused to go down the tunnels. Their spontaneous strike had begun. At midnight, they jeered the few workers who had gone down and made sure that work was halted on the third shift. They spent the night at the work-site, celebrating their new-found solidarity. That’s when the police were called in and the workers dispersed.

The strikers knew it wasn’t a lack of funds that caused the delay. “Those fellows in the office don’t care how they do their work,” said one striker, “the money is here all right, but they don’t want to trouble themselves to make out the roll.” At least one other striker felt that the real issue was how much they received for their labor. “We want $3 a day,” a worker told the Hartford Times.

An alleged threat by the strikers to cut off the air supply to the scabs who crossed the picket line may have contributed to the speed with which the contractor responded to the sand hogs’ demand to be paid. They got their money the next day, as did the stone masons who had also been waiting.

When contacted about the uprising, one construction supervisor denied that there had been any concerted action by the Black workers at all. He told a reporter that an air engine had broken down and that’s why work had been delayed. The sand hogs knew better.

Steve Thornton has been a labor union organizer for 35 years and writes on the history of working people.

This article originally appeared on ShoeLeatherHistoryProject.com