New Britain, fondly known as the “Hardware City,” had numerous companies that contributed to modern industrialization. The Corbin Cabinet Lock Company formed in 1882 and is still in business today as CCL Security. No longer local, the company relocated to Wheeling, Illinois in 2003. Many New Britain manufacturing companies have, for a variety of reasons, either gone out of business or simply disappeared from the business landscape, yet their memory and legacy live on through their intellectual property, better known as patents. Patent rights can be bought or assigned, and patent law protects an inventor’s unique product or procedure from being used without their permission. When another person or company uses an inventor’s product without permission, the inventor can sue the other for patent infringement. The Corbin Cabinet Lock Company was involved in some very early patent law disputes heard by the US Supreme Court. The results of these decisions established precedents in American patent laws that are still relevant today.

Meet the Corbins

Have you ever driven by this sign on I-84?

Did you know that a major shopping center called Corbins Corner in West Hartford is named after the Corbin family? The area was once the Corbin family homestead. Philip Corbin, a major figure in New Britain’s industrial history, along with his brother Frank began manufacturing companies in New Britain as early as 1849. Eventually, the Corbin brothers formed a holding company called the American Hardware Corporation to oversee their various smaller companies. The University of Connecticut’s Thomas J. Dodd’s Research Center’s Archives and Special Collections has financial and personnel records of this corporation that cover the period 1859 to 1944 and states that “the P. & F. Corbin hardware shipping crate was formed in 1902 as a holding company through the merger of the Russell & Erwin Manufacturing Company and P & F Corbin, which were at that time separate and independent and rivals in the market for builders’ hardware. At the time of the merger the two companies produced nearly one-half of the total hardware of this type in the United States. The two merged companies remained as distinct divisions of American Hardware Corporation and two other division—Corbin Cabinet Lock Company and the Corbin Screw Corporation—were added later.”

Left Handed Coffee Mugs and the Corbin Cabinet Lock Company: An Analogy

Can someone patent a left handed coffee mug? The vast majority of readers will (hopefully) say no. From a sound reasonable point of view, “no” makes perfect sense, but what is the legal reasoning for not being able to patent a left handed coffee mug? For that, you would need to consult an 1893 Supreme Court decision involving a case of patent infringement brought against the Corbin Cabinet Lock Company to find out the legal reasoning.

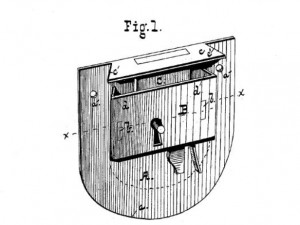

In 1882, Morris Orum was awarded a patent based on the following lock design:

Mr. Orum then assigned his patent to the Duer Company. What is important to understand about this type of lock is that it is considered a “mortise” type lock. That is, there is a cavity in the door or drawer in which the lock fits. Prior to the late 19th century, making such a cavity for the lock was labor intensive and expensive because the craftsman had to chisel out the cavity or recess by hand. Consequently, up until this time most locks were affixed to the outside of the drawer or cabinet door.

Around the time of Orum’s patent, however, machines like routers were making it easy and inexpensive to make these mortise locks with a pre-drilled recess. Lock companies like Corbin Cabinet Lock were manufacturing these types of locks.

The Duer Company felt that making these locks infringed on the Orum patent and sued the Corbin Cabinet Lock Company for patent infringement. Duer lost in lower courts and appealed to the Supreme Court.

Duer v. Corbin Cabinet Lock Co. 149 US 216 (1893)

The Supreme Court decided that Orum’s patent was void and unenforceable. By the time of Orum’s patent, most manufacturers had already figured out how to use routers to make the cavity for the mortise lock and then slip in the locking mechanism. It had become an established part of the art of making locks prior to Orum’s patent. The Court established a test for the patentability of an invention: It had to be novel.

The Court concluded that based on where the design of locks had been and where it was going, anybody with limited expertise would figure out how to make a lock like Orum’s. Justice Brown, who delivered the opinion of the Court, summed up the decision, “In view of the advance that had been made by prior inventors, it is difficult to see wherein Orum displayed anything more than the usual skill of a mechanic in the execution of his device.” So, the fact that other people had been making locks the same way Orum suggested in his patent, before he ever had the patent granted, means his idea was neither new nor novel. Therefore, like the lock, you cannot patent a left handed coffee mug because all you need to do is rotate a right handed coffee cup 180 degrees. In other words, having a handle on the left side of the mug isn’t “novel.”

Resubmitting Rejected Patent Ideas

Let’s say a fledgling inventor submits the left-handed coffee mug idea to the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and they send back the application packet with “Rejected” stamped on it. To make it a novel invention, they re-apply for the patent but state in the application that the left handed mug will be made of ice instead of plastic or ceramic material. This time, the patent is granted.

In celebration, they go to a cafe and order a cup of coffee. The coffee is delivered in an ordinary coffee mug. The inventor shouts, “That’s my idea!” Can the new inventor sue the cafe owner for patent infringement because the coffee was served in an ordinary coffee mug? No, of course they cannot. What then is the legal reasoning for not being able to sue?

Corbin Cabinet Lock Co. v. Eagle Lock Company 150 US 38 (1893)

Look once again at the patent litigation history of the Corbin Lock Company. This time, they are suing Eagle Lock Company for patent infringement for a patent they acquired through assignment from the inventor Henry Spiegel. The problem was that Spiegel’s patent had initially been rejected for making claims that were too broad. The USPTO had told him that he could get the patent granted if he narrowed the scope of the claim of his application. Spiegel did so and he was granted a patent for a very specific claim regarding his lock.

Unfortunately, the Corbin Lock Company brought the patent infringement against the Eagle Lock Company based on the parts of Spiegel’s original patent application that had been rejected as too broad. Consequently, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Eagle Lock Company. Justice Jackson stated the Court’s opinion that Spiegel, “[h]aving originally sought broader claims, which were rejected, and having acquiesced in such rejection, and having withdrawn such claims, and substituted therefor [his] narrower claim, … neither [Spiegel] nor his assignees can be allowed, … to insist upon such construction of the allowed claim as would cover what had been previously rejected.”

So, the inventor of the left handed coffee mug made out of ice cannot sue the cafe owner for using regular coffee mugs without his approval.

What Did We Learn?

The Corbin Cabinet Lock Company was involved in major patent litigation that set forth precedents by the Supreme Court that are basic tenets of intellectual property law today. Inventors of today can be considered entrepreneurs yet whether their idea is patentable or original is based on the scope of their claim and whether it is a novel claim. That is in part because of some very real 19th century entrepreneurs, New Britain’s own Philip and Frank Corbin.

Matt Histen is a graduate student in the History Program at Central Connecticut State University in New Britain. He is also a practicing attorney in Connecticut.