by Steve Thornton

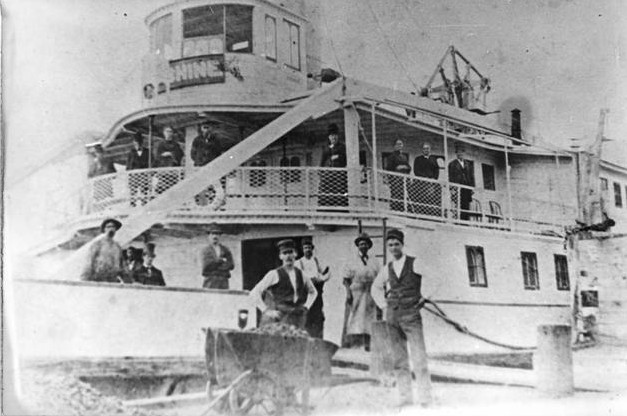

From the Mississippi River to the Connecticut River, steamboats played a major role in building 19th-century America. In Hartford, people would wait for the State of New York to pull up to the river landing stocked with goods from other parts of the nation and around the world. Others boarded the Granite State, an excursion boat that toured points on the Hudson River. But the men who made the steamboats of the Hartford Line run—the deck hands, stevedores, and firemen—found little glamour in the work which normally meant 18-hour days, dangerous conditions, and lousy food.

During the Civil War, able-bodied men were being drafted so the demand for steamboat workers was great. Monthly earnings for deckhands were $30, with stevedores (dock workers tasked with the loading and unloading of goods) making $35, and skilled firemen (those in charge of minding the ship’s boiler) taking home $40. After the war ended, however, the labor supply was plentiful and wages were periodically slashed. Over the next 15 years, steamboat workers earned 30% less than they had during the war.

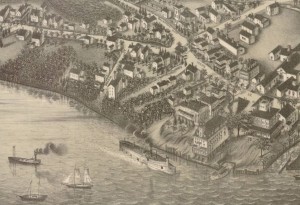

Detail of Goodspeed’s Landing from the bird’s-eye view map View of Goodspeed’s Landing, 1880 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Illustrated

In July of 1879, this pay decline ended. The Connecticut River’s summer level was so low that steamboats from the Long Island Sound could travel no further north than Middletown. William Goodspeed, agent for the Hartford Line, determined that flatboats would have to take the steamboats’ cargo to Hartford. This meant that the freight handlers’ work would double, since they had to unload each steamer and reload onto the flat boats. When the State of New York reached Goodspeed’s Landing, the agent demanded that the workers sign written promises to do the extra duty for the same pay. The boat’s 14 deckhands and four stevedores refused. They picked up their gear and went ashore.

Workers Strike for Higher Wages

Goodspeed responded by advertising for 200 permanent replacements, essentially firing the striking workers. When no one responded to the ad, Goodspeed quickly offered the strikers their old jobs back. They refused until he promised them 10% raises. The firemen, who had apparently not been part of the strike, also won a pay increase.

The strike of the 18 sailors was far-reaching. Goodspeed was soon forced to give pay increases to all the workers on the Hartford Line. And when the workers on the New Haven Line heard about the Hartford action, they demanded and won the raise too.

While all this was taking place, a lone Hartford Line excursion boat was making its way along the southern coast of Long Island and into Lower New York Bay with plans to take its passengers up the Hudson River on a pleasure cruise. When it paused on its journey and docked at Coney Island, the workers heard about the victories. They promptly went on strike to win their fair share, too.

Steve Thornton has been a labor union organizer for 35 years and writes on the history of working people.

This article originally appeared on ShoeLeatherHistoryProject.com