By Brenda Milkofsky

At the time of the American Revolution, British military power surpassed that of any western nation. Yet, the son of a Connecticut farmer, David Bushnell, hoped to prove that creativity and inventiveness might win the day for the colonies.

Born in 1740 in a section of Saybrook that is now Westbrook, David Bushnell was the eldest of five children. Still at home and unmarried at age 26, he lost his father and two sisters in a span of three years. His mother quickly remarried, by custom and necessity, and left the farm to David and his younger brother, Ezra. David sold his half of the farm to Ezra and studied to enter Yale College. Although 31-year-old David was much older than other applicants, he was accepted and entered Yale in 1771.

Bushnell Experiments at Yale

Once in New Haven, Bushnell studied religion, mathematics, geometry, Natural Philosophy–as exploration of the natural sciences was then called–and other topics of interest to a budding inventor. Yale’s fine library included standard 18th-century scientific texts, so Bushnell had access to the best and latest information to support his own research and experiments.

While still a student, Bushnell experimented with methods to make gunpowder explode under water, terrifying onlookers. In April of 1775, Bushnell’s last year at Yale, news of the battles at Lexington and Concord electrified Connecticut. The college closed early and Bushnell went home to Saybrook where he continued to work, now in earnest, on building a submarine that would deliver his underwater mine or explosives.

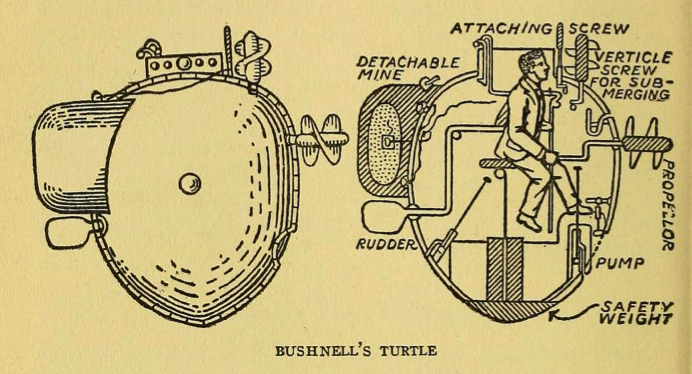

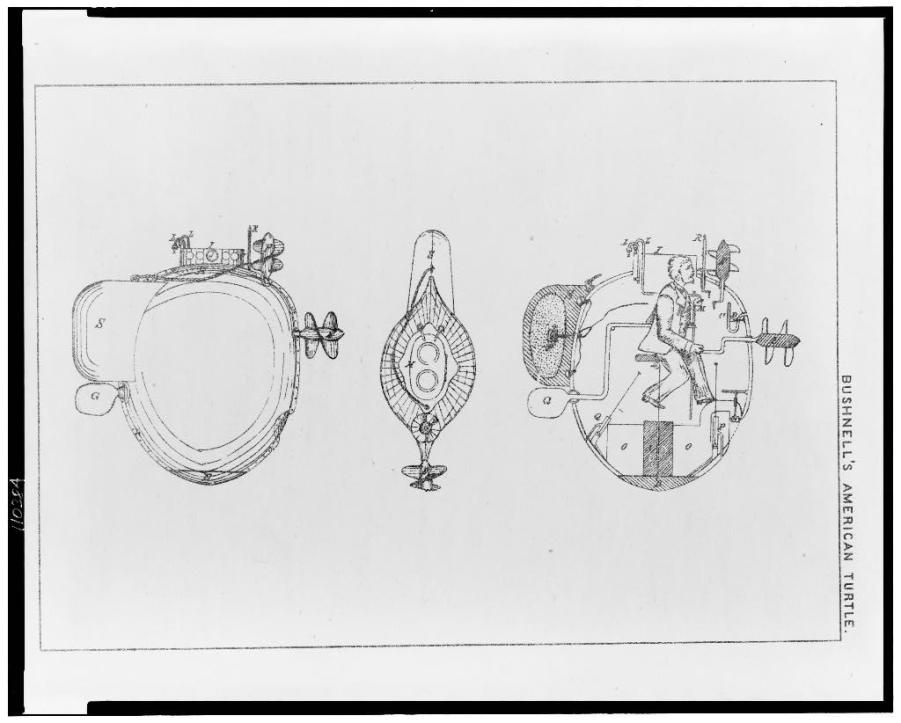

The Mechanics of the Turtle

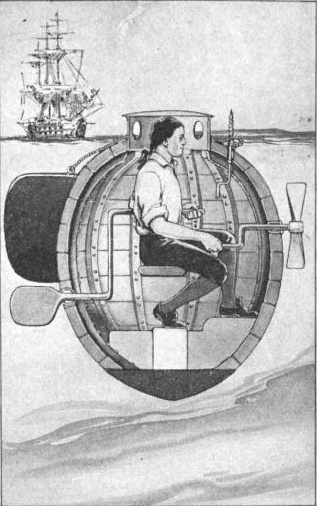

Historians are not sure when Bushnell and his brother Ezra began construction of the submarine that launched in the fall of 1776 and became known as the Turtle. For all Bushnell had read during his studies, he faced the practical challenges of making the underwater boat work. The Turtle would be no mere diving bell tethered to the surface by ropes and air hoses. To be effective, the vessel Bushnell envisioned had to submerge, be able to move forward and backward and rise again to the surface, all while supporting a human pilot or operator. And, it had to carry and deliver an underwater mine. He had to solve many problems—how to supply light and air for the craft, how to gauge direction and depth during operation—and he had to solve them quickly.

The hull of the submarine was constructed of oak, somewhat like a barrel, and bound by heavy wrought-iron hoops. This was the age of wood, and barrels and ships’ hulls were made everywhere along the Connecticut River and Long Island Sound. However, all of the mechanical parts needed for the submarine required the involvement of highly skilled, experienced artisans and crafters.

Bushnell’s American turtle – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

To raise and submerge the vessel, the operator flooded the air-filled chamber with water, making it heavier or lighter as needed, to achieve the desired depth. Bushnell went to a known patriot, Isaac Doolittle, a clockmaker and bell founder, who had a shop near Yale, to manufacture these valves and forcing pumps and, perhaps, the bell-shaped hatch as well.

Real ballast, which is the stabilizing weight needed to keep the boat upright in the water, was affixed to the outside bottom and carried inside as well. To propel the boat forward and backward, Bushnell used a front propeller that was operated by a treadle and a hand crank. During Bushnell’s lifetime, treadles were used to provide foot power to spinning wheels, lathes, and other large tools. A vertical propeller on the top of the boat assisted with ascent. These two propellers that Bushnell invented and described as “oars” and “like the blades of a windmill” were his greatest contribution to future marine development and to his submarine.

The only light that came into the dark vessel was through the small windows in the hatch. Air came into the chamber through two snorkels that closed over when the boat submerged. Because the air inside the submarine was limited by its size, the vessel was designed to travel on the surface or with its hatch and windows above water. It would only submerge to avoid detection and affix the mine.

Clockworks Technology Adapted to War Needs

The mine Bushnell designed was probably keg shaped and about 2½ feet long and 1½ feet in diameter. Packed with 150 pounds of gunpowder, it could put a hole in the hull of a large British warship. The keg mine was to be attached to the enemy ship by a sharp screw cranked into the wooden hull by the operator inside the submarine.

Igniting the gunpowder underwater presented a challenge, as did timing the explosion so that the Turtle and its operator could get safely away. Two clockmakers worked with Bushnell on various aspects of the Turtle project, Isaac Doolittle of New Haven, mentioned above, and Phineas Pratt of what was then called Potapaug and today is the village of Essex. The team modified a clockwork timing device to trigger a flintlock mechanism from a musket. The sparks made by flint striking steel would ignite the priming powder in the pan that in turn would set off the gunpowder. The operator would set the timing device in motion when releasing the mine from the submarine, allowing him enough time to clear the area.

Once the hull and major manufactured parts of the submarine were in place, the boat was moved from Ezra’s farm on the Westbrook Road to what is now Ayer’s Point in Old Saybrook on the Connecticut River, where Bushnell had a Yale connection. Here, the boat had its in-water trials and the operator received training.

Putting the Turtle to the Test

Operating the submarine craft required physical strength and stamina so farmer Ezra Bushnell, not scholar David, was trained as the operator. Through a lengthy correspondence by Bushnell’s friend Dr. Benjamin Gale (Yale, 1755) of Killingworth to Silas Deane, a member of the Congress from Connecticut who served on the Continental Marine Committee, inventor Benjamin Franklin became aware of the project. In turn, General George Washington and Governor Jonathan Trumbull became supporters. By the time the submarine was moved by boat from the Connecticut River to New York, many people hoped for its success.

In June of 1776, a massive British force of warships and transports carrying as many as 50,000 soldiers, hired Hessians, and Marines began arriving in New York harbor. Bushnell hoped to take bold action by sinking the HMS Eagle, the flagship of British Admiral Howe. When the Turtle arrived on a small coastal sloop in mid-summer, the scene must have been frightening. Almost immediately, Ezra Bushnell, the trained pilot, came down with a debilitating fever. Unwilling to wait for another opportunity, David Bushnell applied to Brigadier General Samuel Parsons of Lyme, who was in New York with the 10th Continental Regiment, for volunteers. From those offered, Bushnell chose Ezra Lee, also of Lyme, to pilot the Turtle. To avoid discovery during Lee’s training, they moved back up the Connecticut coast and finally back to Saybrook. After two weeks of training, the mission to plant and detonate explosives under a British ship was rescheduled.

Ezra Lee described the event: “We set off from the City, the Whale boats towed me as nigh the ships as they dare go, and then they cast me off. I soon found that I was too early in the tide, as it carried me down to the [transport] ships. I however, hove about, and rowed for 5 glasses [2½ hours], by the ship’s bells, before the tide slackened so that I could get along side the man of war, which lay above the transports.”

Unable to “row” with the propellers against the tide, Lee had spent two and a half hours “treading water” to avoid being swept away. Rowing the Turtle meant using his legs to rock the treadle back and forth while also turning the hand crank. By the time the tide turned, and Lee maneuvered near Admiral Howe’s flagship, the sun was coming up and he was exhausted from his efforts.

A depiction of David Bushnell’s submarine

Later, Lee described his unsuccessful attempt to fasten the mine. “When I rowed under the stern of the ship, could see men and deck and hear them talk-then I shut all doors, sunk down, and came up under the bottom of the ship, up with the screw against the bottom but found that it would not enter.” Unable to affix the mine and with daylight upon the water, Lee decided to make for shore before the vessel was discovered by passing boats. But it was too late. Guard boats put off from shore in his direction and soldiers mounted the fort on Governor’s Island to catch sight of the strange craft.

Lee writes that he “let loose the magazine [mine] in hopes, that if they should take me, they should likewise pick up the magazine, and then we should all be blown up together…” Ezra Lee did not lack courage, only experience in a craft no one on earth had ever before piloted in action. The mine did explode, frightening off the pursuing guard boat; Lee escaped with his life and with Bushnell’s machine.

Following Lee’s ill-fated mission, Bushnell and his supporters took the submarine up to the Hudson River, where Lee again was unsuccessful in blowing up a ship. Following the first mine explosion, the British Navy warned their mariners to keep a sharp lookout. Lee and the Turtle were discovered and then swept off target by the tide. Even Phineas Pratt, the other trained operator, met with failure when moonlight revealed the Turtle to watchful British eyes and they fired upon the craft. A few days after these two unsuccessful attacks, the British sunk a number of vessels including the one carrying the submarine.

The Father of Submarine Warfare

Although the patriots recovered the vessel, David Bushnell was in poor health and he later wrote, “I therefore gave over the pursuit for that time, and waited for a more favorable opportunity, which never arrived.” Bushnell did develop other mines that could be delivered without his submarine. The Continental forces used one type in New London Harbor and another on the Delaware River; both were successful.

When the war ended—and with brother Ezra having died in 1786—David Bushnell left Connecticut and went to Warrenton, Georgia, with Yale classmate Abraham Baldwin. There, he taught at Franklin College and continued to work on delivery systems for underwater mines. Not long before he died in 1826, Bushnell was in contact with the US Department of the Navy about a floating torpedo.

David Bushnell’s submarine invention and underwater mine were first made known to the American public in 1798 when future-president Thomas Jefferson gave a lecture to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. He used as the source for his talk a 1787 letter to him from David Bushnell documenting in detail both inventions. Later printed, that description in Bushnell’s own language is the basis for his honor as the Father of Submarine Warfare.

Brenda Milkofsky was Director & Curator of the Connecticut River Museum in Essex, Connecticut, when the very first working reproduction of Bushnell’s submarine was built and successfully tested in waters off the Museum, where the story continues to be told.