By Richard Malley

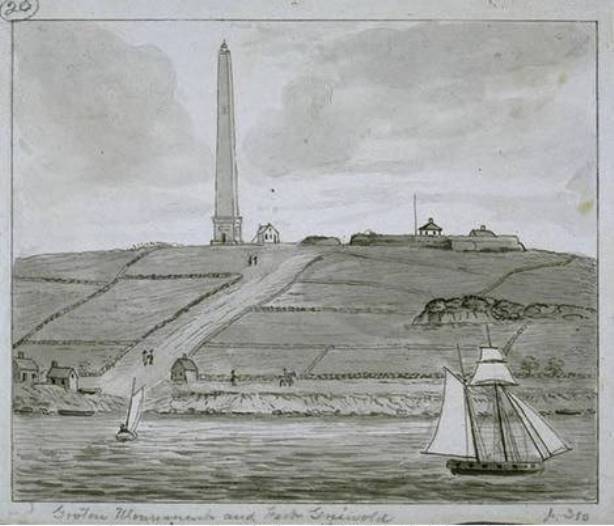

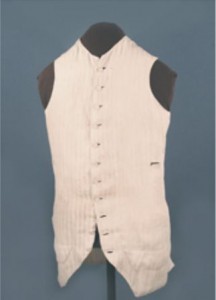

Linen Vest, about 1781. Col. William Ledyard’s linen vest came to CHS from his daughter-in-law Maria Ledyard. Note puncture hole in the side, suggesting a bayonet wound – Connecticut Historical Society

Linen Shirt, about 1781. A puncture hole on Ledyard’s linen shirt matches that in the vest. The absence of discoloration on shirt and vest is attributed to a thorough bleaching of the clothing in the 19th century – Connecticut Historical Society

Detail of Linen Shirt, 1781. This detail shows the puncture hole in Ledyard’s shirt – Connecticut Historical Society

By 1781 it was becoming apparent to both sides that outright British victory in the American Revolution was unlikely, in part due to the commitment of French troops and other resources that would culminate in the successful Yorktown campaign in October 1781.

Connecticut native Benedict Arnold, a skilled military leader who switched his allegiance to Britain, was ordered to attack the port of New London in an attempt to divert some of General George Washington’s army away from the developing Virginia campaign, punish New London for its successful privateering operations against British shipping, and possibly to establish a base for future British military operations in New England.

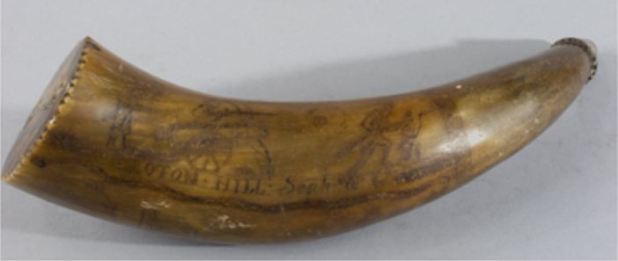

The citizens fled the town, and Fort Trumbull, guarding the west side of the river, was quickly abandoned as Arnold’s force of about 1,700 men landed from the British ships anchored off New London. The British troops set to destroying military and naval supplies and accidentally caused a fire that soon spread, burning much of the town. Meanwhile, across the river in Groton, militia forces commanded by Colonel William Ledyard had manned Fort Griswold, a substantial fortification atop Groton Heights, a hill overlooking the Thames River. American cannon fire caused considerable casualties among the British when they attacked the fort, but additional assaults finally breached the fort’s defenses.

Fort Griswold Massacre Remains a Matter of Debate

What happened next is a source of controversy. Colonel Ledyard, seeing his troops were outnumbered, ordered the surrender of the garrison. According to some accounts, Ledyard was run through and killed with his own sword when he surrendered it to the British officer in charge. Other evidence suggests Ledyard may have died from a bayonet wound instead. What is clear is that confusion reigned, and it is possible that Ledyard’s order to surrender was not received by all the militia, leading the British to continue firing at the Americans. Following the battle the British withdrew, leaving death and widespread destruction on both banks of the Thames.

More than 100 Americans were killed and scores more were wounded. Many of the captured militiamen were taken to New York and imprisoned for months. Public passions were stirred by reports of the “massacre” and its particulars remain a topic of debate to this day. Fort Griswold was rebuilt and today is part of Connecticut’s state park system.

Richard Malley is Head of Collections at the Connecticut Historical Society.

© Connecticut Public Broadcasting Network and Connecticut Historical Society. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared on Your Public Media.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.

Powder Horn, about 1781. Artilleryman Henry Mason of Groton was captured when British forces stormed Fort Griswold. His powder horn was subsequently engraved with scenes from the battle – Connecticut Historical Society, 2012.571.0.