By Steve Thornton

In 1901, all Hartford saloons sold a glass of beer for a nickel. But if a thirsty man bought the same beer from a shop without a union card hanging behind the counter, it would cost him $2. That’s because the local Hotel, Restaurant and Bartenders’ Union had posted warnings in every union hall that the price of drinking a scab beer would cost union men roughly a day’s pay. How such a fine was enforced is not known, but the point was clear: Hartford was a union town. The barmen’s fight to reduce working hours to 62 a week and raise weekly pay from $9 to $15 would not be compromised by careless workers who forgot that union solidarity was their only weapon against exploitation.

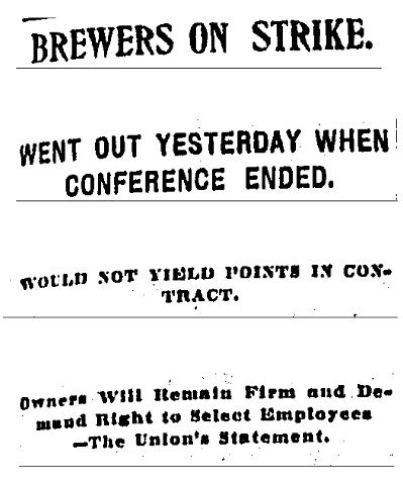

The next year, local union beer makers were hoping they could come to a compromise with Hartford’s brewery owners. They negotiated for over a month, and several times the workers postponed the one final action that would force the bosses to settle–a strike.

Local 35 of the Brewers Union

In the meantime, the four beer companies were making plans of their own. It was 1902–a new century, after all–and the growing power of unions called for new strategies by bosses. So the Hartford owners began to work together, resisting as a combined group the demands of Local 35 of the Brewers Union.

The companies decided they would no longer choose their new employees from the Brewers’ Union hiring hall. The owners believed that the closed shop, as it came to be known, was a further restriction on management rights. If we need a skilled “stationary engineer,” they argued, we should be able to hire one even if he isn’t a Brewer’s Union member. (A stationary engineer typically operated and maintained boilers and other mechanical systems.) Another major sticking point was how to handle the termination of a brewery worker. Owners wanted an outside arbitrator, mutually agreed-upon with the Union, to make the final decision. The workers said no. The Union also demanded the 8-hour work day and better job security during slow production times in winter.

In a real sense, this was not the traditional labor fight over wages and hours. It was about power. The owners had reportedly agreed to economic demands but were holding out for concessions on hiring and firing. To the Union, who was on the job was as important as how much they were paid. In no other trade were such rules in effect, the owners complained. A local newspaper warned that other brewery unions in Boston, Springfield, and Buffalo had tried to win these demands and given up.

The Union had significant support in its fight. The local building trades, clerks, and metal workers’ unions offered moral and financial aid. The head of the Brewer’s Union in New York, along with Louis Eisel, John Doyle, and Matthew Kelly of the Hartford Central Labor Union, headed the negotiations with the owners. And most significantly, there was a “non-interference” agreement from union breweries all over the country that in case of a strike, no additional beer would be shipped into the city.

Strike Halts Production—and Beer Drinking by Union-Minded

Finally on April 11th, beer makers struck all four breweries: Hubert Fischer, New England Brewing, Aetna Brewing, and Ropkins & Company. The beer that had just been produced stayed in the plants. “We believed that the bosses had broken their word” on demands that had already been settled, said Union spokesman Richard Merchenz. Workers at two of the firms couldn’t even wait until the designated starting time of 1:30 pm and walked out at noon. Production went from 400 barrels a week to zero, affecting 75% of all the beer consumed in Hartford’s many bars and taverns.

Eighty-five mostly German brewery workers were on strike, some of whom had worked at their jobs for 20 years. Members of the engineers’, firemens’, and drivers’ unions who also worked at the breweries walked with them in solidarity. The normal wages for these additional workers ranged for $15 to $20 a week depending on the job, with 50¢ an hour for overtime (there was a lot of overtime during the summer months).

The strike was cause for a re-examination by Hartford workers of their commitment to the unionism and particularly union-made goods. According to news reports, men checked each other’s suits for union labels and chastised those who smoked non-union tobacco. Some even began to drink ginger ale.

The strike was not without controversy. At least one teamster who hauled beer was upset that a scab would now be handling his horses. And the beer workers decided that any pre-strike beer was “unfair” and should not be bought. This put Union bartenders like T.J. Sullivan in a quandary, since they had been serving union brew produced before the strike. Saloon owners had built up their supplies in anticipation of a job action and if it couldn’t be sold, it would spoil.

The Union went to bars all over the city to make sure owners were not buying scab beer, even though the four breweries were completely shut down. They also went to other unions and asked them to pledge not to drink beer until the strike was settled. For the hard-working, hard-drinking members of Hartford’s working class, this was a significant act of solidarity.

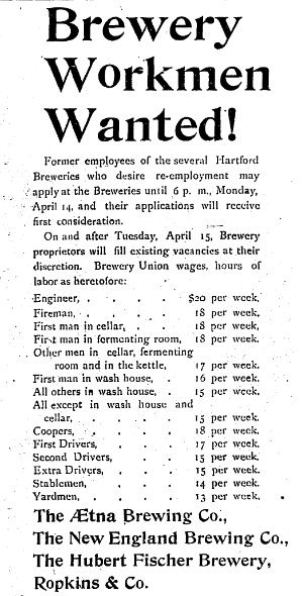

The owners were not idle. Needing transportation of their product, they tried to hire two different local hauling companies. Both were union, and both refused. Then, the bosses went to the Connecticut Free Employment Bureau to seek job applicants. Within a few days of the walkout, the owners were hoping to be ready to start production with a scab labor force.

But within six days (including one Saturday night), the strike was over and the workers had won. Bartenders’ Union leaders J.J. Murphy and T.J. Sullivan got involved and spoke to both the strikers and the owners. The result was impressive by any standard: the Brewers’ Union won the 8-hour day (9 hours for drivers); new workers would come only from within the Union’s ranks; and fired workers could have their cases heard by an arbitration panel composed of Central Labor Union officials.

And the brewery workers won five minutes off each hour to drink beer.

Steve Thornton has been a labor union organizer for 35 years and writes on the history of working people.

This article originally appeared on ShoeLeatherHistoryProject.com