Written by William Devlin for the Connecticut History Review

They danced on the green. They passed around a “kiss of peace” between members at a communal meal, shared in the middle of their day-long service held at a special “eating house.” Their clergy didn’t need to be trained. Their practices earned them the derisive nickname of “Kissites.”

They were the Sandemanians of Danbury, a vanished semi-communal sect whose outsized influence outweighed its tiny numbers. A breakaway sect of the Scottish Presbyterian Church, their name comes from Robert Sandeman, son-in-law of their founder, an early 18th-century Scottish Presbyterian minister named John Glass. Their keystone beliefs were that a profound faith experience was unnecessary and that the Bible, especially the New Testament, was to be interpreted absolutely literally.

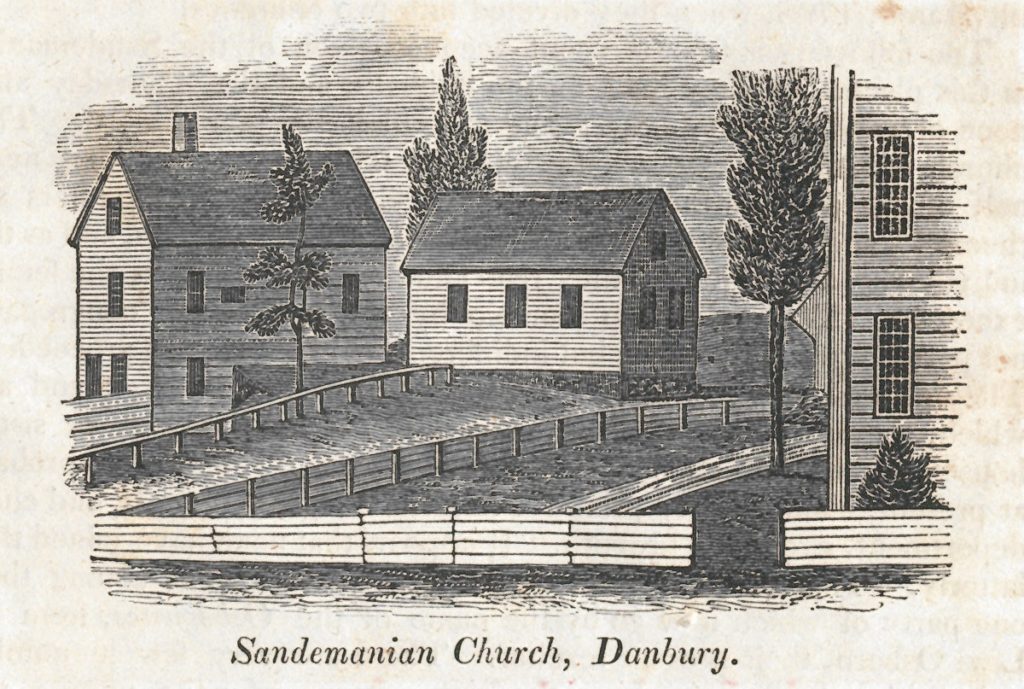

Danbury Becomes Home to the Sandemanians

In the mid-1700s, Robert Sandeman’s published writings intrigued a number of Connecticut Congregational ministers, who wrote to him. Encouraged by this response, Sandeman did a grand tour of the American colonies, leaving congregations in his wake in several Connecticut towns including Newtown and New Haven, and ending in Danbury where the town’s long-time minister, Rev. Ebenezer White, welcomed him. While White disagreed with some of Sandeman’s points, particularly about the need for an educated clergy, several of White’s sons and other townspeople became followers. After successfully defending himself against charges of overstaying in the town, Sandeman settled in Danbury and died there in 1770.

The Sandemanians’ embrace of strict neutrality put them in the crosshairs of rebel authorities during the American Revolution. Members were rounded up, interrogated, exiled, and even shot at. The war put a damper on the sect’s growth, and congregations in several towns began to decline, except in Danbury. Talented and entrepreneurial Sandemanians from dwindling congregations elsewhere in Connecticut relocated there, laying the foundations for its evolution into the “Hat City.”

Oliver Burr, cousin and onetime guardian of the young Aaron Burr, came from Newtown to partner with Russell White, one of the Rev. White’s sons. The Sandemanian partners created Danbury’s first large-scale hat firm. In 1787, Burr & White hired an English master hatter to teach journeymen, began to import furs from Canada, and started churning out thousands of men’s hats a year for sale through a showroom in New York City.

Powering Danbury’s Industry

By the mid-19th century, the country’s largest hat factory was in Danbury, run by Abijah Tweedy, another Danburian with a Sandemanian connection. (His father William Tweedy had been a practicing Sandemanian, and his great-grandmother had been the first of the family to join the church, in the 1770s.) Another Tweedy, Samuel, also a hat manufacturer as well as a banker, became the first Danbury resident to be elected to Congress.

Nathaniel Bishop, comb manufacturer and Elder of the Danbury Sandemanian congregation in the mid-nineteenth century. – Danbury Museum and Historical Society.

For a period in the 1820s and 1830s, Danbury’s hat industry was rivaled in importance by comb making. A local cottage trade, it received a boost when Nathaniel Bishop left the near-defunct New Haven congregation to lead Danbury’s Sandemanians as their Elder. He founded a firm that for 35 years sold its ornamental combs of shaped cattle horn that proved popular with women in South America.

Membership in the Sandemanian sect required a wholehearted commitment, but divisions and disagreements eventually decimated the sect’s already small numbers. As complete unity was required on all issues, a dissenter who persisted could be excommunicated and completely shunned. One dramatic and painful rift involved Oliver Burr’s desire (in the late 1780s) to build a house of his own, which could also be used as the group’s “eating house.” The group believed that because work was a virtue, members should strive for material success, but that they should not “store up wealth in this world.” Instead, they should share any surplus wealth with poorer members. Russell White wrote heartbreakingly in a memoir of how, because of the controversy, “the church began to degenerate from the Philadelphian (brotherly) state.” Despite further rifts over the years – one of which created a group that was one of the founding congregations of the Disciples of Christ Church – Danbury’s Sandemanian congregation soldiered on through the 19th century, a local curiosity.

The group’s insistence on Biblical-style patriarchy required males to lead services, creating another fatal problem as males in the congregation died or drifted away. The last acknowledged head of the Danbury Sandemanians, Lucy Ely, died in 1899, ending the sect’s history not only in Danbury but in the United States.

William Devlin was a history teacher, an adjunct instructor of geography at Western Connecticut State University and is the author of books and articles about Danbury-area history. He has been a longtime volunteer for environmental causes. This story is based on his longer paper for the Fall 2017 issue of Connecticut History Review.