Jason R. Mancini, Ph.D.

Author’s Note: The use of the term “Indian” is problematic but must be contextualized. Tribal specific labels are preferred, though often “Native” and “Indigenous” are used now in place of “Indian” as generalized descriptors. In the US, the term “Indian” has legal and political significance to tribes and how they manage their relationship with state and federal governments. “Indian” is codified in the U.S. Constitution and in subsequent “Federal Indian Law” and the “Bureau of Indian Affairs.” Historically, “Indian” people were excluded from the federal census (1790-1860) or relabeled using other race categories like “mulatto” or “colored” that resulted in their erasure from colonial, state, and federal records, a process that Native people describe as “pencil genocide.” Some tribal communities today self-identify using the term “Indian” including the Narragansett Indian Tribe, Schaghticoke Indian Tribe, and Shinnecock Indian Nation. Keeping this in mind, to better connect readers to the historical documents that serve as the foundation of this article, the term “Indian” is used to describe the Indigenous peoples of New England (and their descendants) when specific tribal labels are not applicable.

By the early 1800s, most white visitors to the local Indian reservations noticed and commented that the residents “for the most part [were] very aged persons, widows, and fatherless children.” But over the past twenty years, through a deeper understanding of the hidden and nuanced histories of American Indians—Pequots, Mohegans, Narragansetts, Wampanoags, and Shinnecocks to be specific—it has become clear that many hundreds went to port and to sea and often in groups. Indian men were involved in shipbuilding, notably as riggers. They served on naval, commerce, whaling, and even pirate vessels. They were coopers, stewards, cooks, seamen, mates, marines, captains, and ship owners. Some went to sea once. Some spent their lives at sea. Many gave their lives. These untold tales reveal that Indians were not relegated to isolated reservations. Rather they, like their white neighbors, were present and actively engaged in many events that shaped colonial history locally, nationally, and internationally.

Tracing Indian Mariners

The most expansively narrated account of Indian travel comes from Paul Cuffe Jr., who chronicled his seafaring career in his 1839 memoir entitled, “Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Paul Cuffee, A Pequot Indian: During Thirty Years Spent at Sea, and in Traveling in Foreign Lands.” Son and namesake of the famed Wampanoag-Ashanti maritime entrepreneur and abolitionist, Cuffe, Sr., he detailed the routes, cargoes, and peoples encountered during his travels, providing a rare (and possibly the lone) opportunity to examine an Indian mariner’s career.

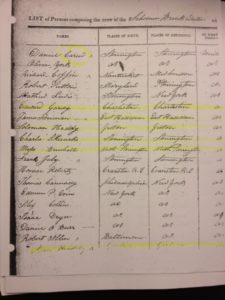

Daniel W. Lamb’s 1896 narrative “History of A Sealing Voyage On board the Schooner Breakwater of Stonington Connecticut in the year AD 1830 and 31,” however, does mention two Pequot mariners, Moses Brushell and Henry Shantup, who traveled with him and shared all of the experiences related in his account. (Lamb was not an Indian.) A third Indian mariner, Charles Skesucks, appears on the official crew list but not in Lamb’s account. [Note: this is the only known reference to Skesucks’ existence, but his surname is present in Mohegan and Pequot tribal records. There might have been a last minute change to the crew since Lamb is the only person from his account not identified on the official crew list.]

In his account of the 1830-31 voyage, Lamb provides a list of the crew and other vessels bound to the South Atlantic. Even before they arrived at their destination, unforeseen events altered their voyage. Below are excerpts from the account that have been furnished by Lamb’s great-great-grandson, Lee Hartman:

So having obtained A release from Capt Smith and pay for work I [Daniel W. Lamb] had done for him up to the latter part of July I shipped on board the schooner Break Water A fore and aft schooner of about 90 tons, Manned by the following named crew. Capt Daniel Carew of Stonington, first mate Oliver York, of Stonington Second mate, Mr Coffin, of Stonington third mate, Robert Sutton, of Stoneington. Steward, Matthew Flores A Portuguese of the Western Isalnds, these were A family by themselves on board the vessel and lived in the cabin. The following were the crew they lived in the forecastle. Cook Solloman Heding A Negro, hands before the mast Robbert Allison of New York, Alexander Collins New York, Thomas Canada New York ____ Duryea Carpenter New York, Edmund P Irvin New York Daniel OBrian New York Moses Brushell of Groton A Pequot Indian, James Freman of Groton A Negro Frank Joseph A Portaguese of Western Isalands. Horrace Robberts Rhode Isaland. Edward Gardner of Rhode Isaland A Negro. These names together with my own show A crew of thirteen men before the Mast and four in the Cabin in all seventeen…[eighteen men appear on the original crew list and one was later added from the Schooner Free Gift].

… And so we witnessed the sad sight of A vessel burning at sea and thus ended the career of the Free Gift after serving her owners about twenty four years. Those of her crew who came aboard the Breakwater were Capt Hall of Stonington Wm Kenedy of Maine Alonzo Hedding and Pharao Hedding Negroes and brothers of Groton and Shumtup A Pequot Indian of Groton …

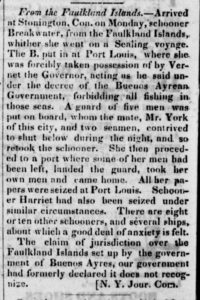

Lamb’s account is interesting and significant both for the detailed (and verifiable) account he provided 65 years later and because the Schooner Breakwater and her crew found themselves at the center of an emerging and enduring maelstrom—an international dispute over the sovereign status of the Falkland Islands.

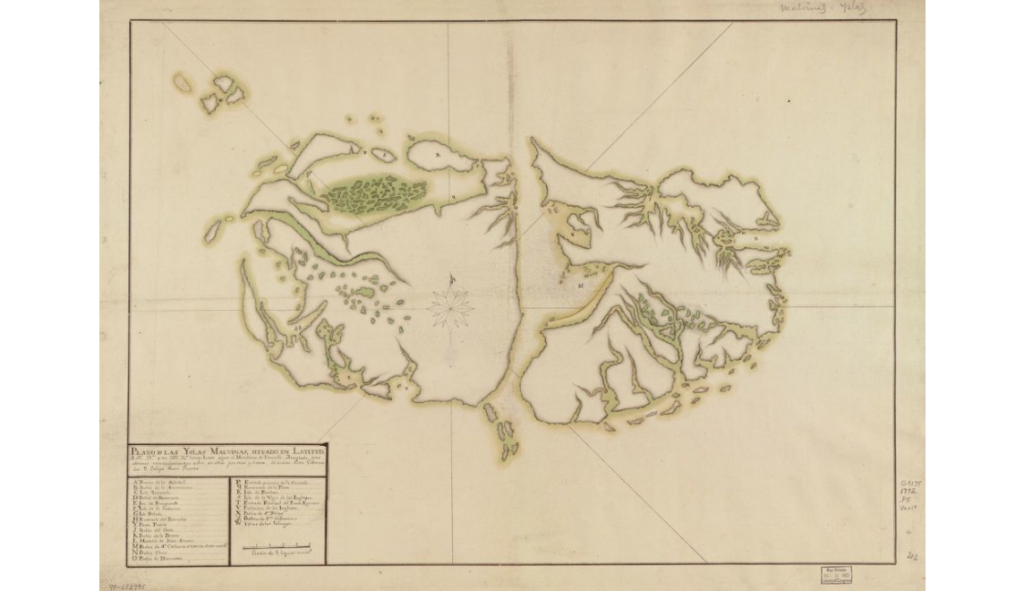

The Falkland Islands Dispute

Description of the Breakwater’s capture in The Rhode Island Republican, November 1, 1831 – Library of Congress, Chronicling America

Until this event, the Falkland Islands had been sparsely settled with temporary French, Spanish, English, Argentine, and American outposts. Beginning in the 18th century, they were used to resupply maritime vessels and by the 1810s and 1820s, the Falklands became an important place for hunting fur seals—in which a number of local Stonington vessels participated. Beginning in 1828, however, the Buenos Aires government, by giving authority (as well as exclusive fishing and sealing rights) to a new governor of the Falkland Islands, Louis Vernet, it essentially issued a proclamation of sovereignty over the islands. Vernet asserted his authority by seizing several American vessels including the Stonington schooner Harriet, brig William, and, later, the schooner Breakwater. Several crewmembers of the Breakwater, including the captain, had left the schooner to visit Port Louis when Vernet seized the Breakwater.

Though a remarkable turn of events, the first mate, Oliver York, and others were able to retake the vessel, leave their former captors behind, and resupply in Pernambuco, Brazil, eventually returning the Breakwater home to Stonington.

The crew arrived in Stonington without further incident, but the event was captured in several American newspapers. Capt. Carew and the others were repatriated to the United States soon after their imprisonment. By October 1832, Carew and several members of his Breakwater crew, including Moses Brushell, Pharaoh Heady, and James Freeman sailed aboard the Schooner Frances of Stonington. Bound to the South Atlantic, they almost certainly resumed their seal hunting. This time, Brushell went to sea with family—probably a younger brother, Solomon.

Impact of the Breakwater Incident

Henry Shantup, Moses Brushell, and (possibly) Charles Skesucks, were participants in a significant international standoff. This account of the Schooner Breakwater allows us a glimpse of Indian lives far away from home. Other Indian mariners would be privy to events that would soon follow, including the Treaty of Waitangi (New Zealand, 1840) and the Great Mahele (Kingdom of Hawai’I, 1848). How did events such as these inform mariner’s lives—materially, politically, and socially? How did they impact their lives back home? By dismantling the notion that Indians only lived on reservations, and acknowledging the fact that they traveled everywhere, many new stories emerge.

The Breakwater incident resulted in at least two important court cases. One, Oliver York v. Schooner Breakwater (1832) involved the first mate, York, who “libelled” or claimed the schooner as salvage—that is, because of his action to reclaim the vessel that would have otherwise been lost, he believed that he was entitled to some level of ownership and financial compensation. York was awarded one-third of the proceeds of the vessel and its contents. A second case, Williams v. Suffolk Insurance Co., pitted the owner of the Breakwater against its insurers. It was determined that the underwriters were “not discharged from their liability.” The case was so significant to insurance claims and liabilities that the 1839 United States Supreme Court ruling continues to be referenced in American law books.

This story and many others like it demonstrate that Native peoples were not bystanders to history but every bit a part of it. Tribal families preserve some of the stories and materials their ancestors brought home from their travels. Others can be found in museum collections and archival repositories. Importantly, there are direct lines between these stories and tribal communities today. For example, Moses Brushell and his wife, Sylvia, had a daughter named Tamar. Tamar later married a Brazillian or Portuguese mariner named Emanuel Sebastian and they had nine children. Their descendants are citizens of both the Mashantucket and Eastern Pequot tribes.

Author’s note: This article is a part of a larger effort to document the global presence and experiences of New England’s Indian mariners. It presents a series of initial thoughts regarding a particular voyage that provides witness to the Indian presence in the American seal fishery. I am grateful to Lee Hartman for generously sharing this narrative written by his great-great-grandfather in 1896. For more on Indian mariners, visit: www.indianmarinersproject.com. For more on Moses Brushell, visit the Native Northeast Portal, here.

Jason R. Mancini, PhD, is executive director of Connecticut Humanities, a former executive director of the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center, and author of the article “Beyond Reservation: Indians, Maritime Labor, and Communities of Color from Eastern Long Island Sound, 1713-1861″ in Gender, Race, Ethnicity, and Power in Maritime America (Glenn S. Gordinier, editor; Mystic, CT: Mystic Seaport, 2008). A version of this article was originally published in the Fall 2013 edition of Historical Footnotes: Bulletin of the Stonington Historical Society from the Stonington Historical Society.