By Patrick J. Mahoney

Despite his relative historical anonymity at a national level, Connecticut’s Oliver Wolcott, who was a signer of both the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation, remains one of Connecticut’s most significant and understudied revolutionary figures. His experiences during the Seven Years’ War and American Revolution made him a sought-after leader for the inexperienced American military, while his background in colonial politics ensured he made significant contributions to shaping the political landscape of the emerging American nation.

Wolcott Chooses A Career of Political and Military Service

Oliver Wolcott, a native of Litchfield, Connecticut, attended Yale College and graduated in 1747. Immediately upon graduating, he received a captain’s commission from New York Governor George Clinton. In his career as a colonial militiaman, Wolcott served on the northern frontiers in the Seven Years’ War, fighting against the French and their Native American allies in the region until the war’s end.

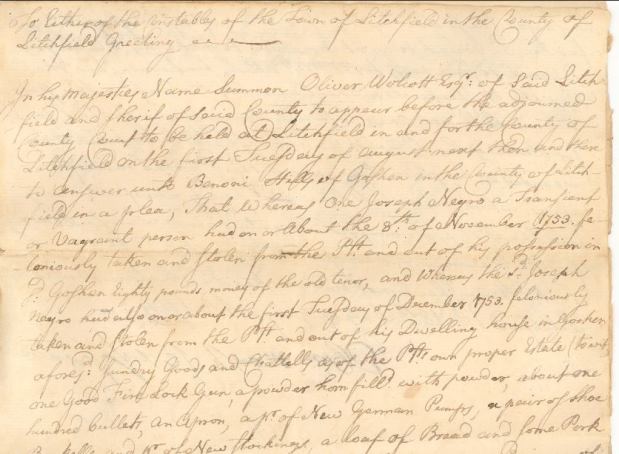

Detail of the writ, Benoni Hills v. Oliver Wolcott – Joseph Negro, a transient person, was accused of stealing goods from the house of Benoni Hills of Goshen in November 1753. Arrested and lacking resources for bail, he was jailed in the Litchfield County jail. He escaped in early 1754 and disappeared. Thereupon, Hills brought suit against Litchfield County sheriff Oliver Wolcott for dereliction of duty. Wolcott was found guilty before the Litchfield County Court in August 1754 – Connecticut State Library, State Archives, RG 003, Judicial Department, Litchfield County Court. Used through Public Domain.

Following the conflict, Wolcott returned to Connecticut to study medicine with his uncle, Dr. Alexander Wolcott. Rather than pursue a career in medicine, however, Wolcott settled in the newly developed area of Litchfield County (where his father owned property) and pursued an entirely different career path. He thrived in the fledgling community, procuring the appointment of county sheriff at the age of 25 and founding a successful mercantile business.

His success also extended to the field of politics, as evidenced by his election to represent Litchfield in the General Assembly, election to the lower house and upper houses of the colonial and state legislatures, and his later appointments as judge of the Litchfield Probate and County Courts. Collectively, Wolcott’s early experiences helped form the foundation on which his later successes emerged during the Revolutionary period.

Revolutionary Rumblings

As news of heightened tensions in Massachusetts began to spread throughout the colonies during the late 18th century, town meeting halls became havens of debate at which colonists attempted to establish their communal stances on the impending conflict with Great Britain. One such meeting occurred on the evening of August 17, 1774, in Litchfield, Connecticut. The moderator of the assembly and judge of the local Litchfield County Court, Oliver Wolcott, had been named major of the Thirteenth Militia Regiment three years prior, and colonel of the Seventh Regiment that year. Given his background, it pleased him to find that, at the meeting’s conclusion, local legislators passed a motion denouncing the Intolerable Acts and promising “all reasonable Aid & Support” to their neighbors in Massachusetts.

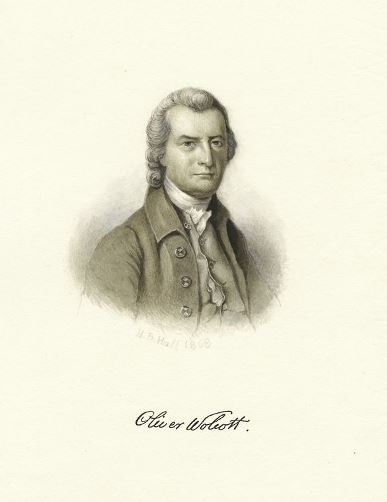

Oliver Wolcott – By Henry Bryan Hall, The New York Public Library Digital Collections, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs. Used through Public Domain.

Although Wolcott proved enthusiastic in his support for the American independence movement, like many others in the colonies, his support and subsequent involvement came at a price. Shortly after the battles of Lexington and Concord, Wolcott reflected on the future prospects of his mercantile career in what was a changing social and political atmosphere, noting, “With regard to my own Business, I have neither time nor opportunity.”

An ardent proponent of independence since his election to the Continental Congress in the fall of 1775, Wolcott noted in April 1776 that, “a final separation between the countries I consider as unavoidable.” In the summer of that year, a brief illness and Wolcott’s increasing role in military affairs drew him away from his political responsibilities, resulting in his absence from Congress during the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. Despite his absence at that watershed moment, he signed the parchment copy of the Declaration that autumn (and also later signed the Articles of Confederation in the summer of 1778).

Advancing American Independence

While his congressional comrades in Philadelphia declared the colonies to be independent sovereign states free from the British empire, Oliver Wolcott was in New York, where he commanded fourteen regiments of Connecticut militiamen engaged in the defense of that city. On the evening of July 9, Wolcott and his men listened to George Washington read a copy of the Declaration to the throng of troops. Recognizing that the political advancement of their cause had finally caught up with the military efforts that had been underway for over a year, a large celebratory demonstration erupted in the streets. During the revelries, patriots tore down a 4,000-pound leaden and gold-leafed equestrian statue of King George III. To rid themselves of the unwelcome symbol of their colonial past, the torrent of patriots quickly dismembered the fallen statue. What was left of the King’s head ended up as a triumphant decorative piece outside a tavern where many of the revelers retired. Patriots gathered the remaining pieces and brought them to Connecticut, at which point symbolism gave way to practicality, and Wolcott and his associates melted down the pieces and converted them into some 42,022 bullets.

The following year, Wolcott and his men proved ready to put these munitions to use, helping defeat General John Burgoyne at the Battles of Saratoga. Shortly after, in recognition of his efforts, Wolcott received a promotion to major general in command of all Connecticut militia. He spent the remainder of his military career defending the state’s coastal communities from possible British attacks. Reflecting on the likelihood of such, he noted that his imperial opponents were, “a foe who have not only insulted every principle which governs civilized nations but by their barbarities offered the grossest indignities to human nature.”

In the post-independence period, Wolcott returned to politics. His constituents elected him lieutenant governor of Connecticut in 1786, and he became the 19th governor of Connecticut ten years later. He died in office in December of 1797.

Patrick J. Mahoney is a Research Fellow in History & Culture at Drew University and former Fulbright scholar at the National University of Ireland Galway