When the United States Senate first convened in 1789, many expected it to be a fairly passive body, similar to the state senates on which it was partly modeled. Aside from acting on nominations and treaties, the Senate’s principal job was seen as reviewing legislation crafted in the House of Representatives. Although this anticipation proved fairly accurate for the first several decades, there are notable exceptions. The Judiciary Act of 1789, almost exclusively the Senate’s handiwork, profoundly influenced the nation’s judicial and constitutional development to the present day.

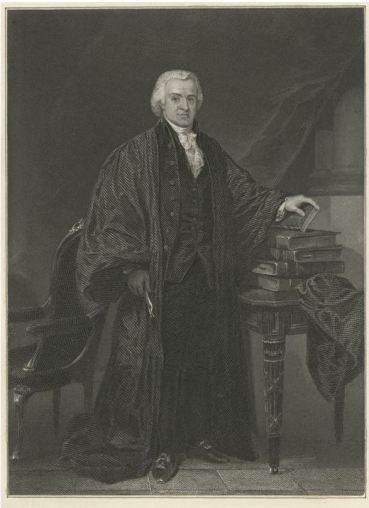

On April 7, 1789, the day after achieving its first quorum, the Senate appointed a committee, composed of one senator from each of the 10 states then represented in that body, to draft legislation to shape the national judiciary. As Connecticut’s Oliver Ellsworth received the most votes for that assignment, he became the panel’s chairman.

Establishing the Federal Judicial System

The Constitution barely mentions the judiciary’s structure beyond providing for a supreme court and any lower courts that Congress might wish to establish. It is silent on the Supreme Court’s size and frequency of sessions as well as judges’ qualifications and compensation.

Oliver Ellsworth was ideally suited to serve as principal author of the Judiciary Act. He had shaped the Constitution’s first draft and its crucial “Connecticut Compromise,” which produced a bicameral Congress with the states equally represented in the Senate. His Senate colleagues had also selected him to chair a committee to draft the chamber’s rules of procedure. Ellsworth quickly won wide respect for his diligence or, as one biographer has put it, “his recognition of the fact that in the senatorial office drudging spadework was even more important than speeches and votes.”

On July 17, 1789, the Senate enacted its version of this landmark statute. With House revisions, it became law two months later. Oliver Ellsworth remained a highly effective senator until 1796, when he moved to the Supreme Court as chief justice of the United States. Although Ellsworth, more than any other, shaped the federal judicial system, his strengths as a legislative craftsman failed to translate to success as a jurist. Deteriorating health forced his resignation within four years.

Today, constitutional scholars remember Oliver Ellsworth’s Judiciary Act as “the keystone of American federalism” and they note John Adams’s assessment that, in the federal government’s earliest years, he was its “firmest pillar.”

Senate Historical Office, Unites States Senate