On April 12, 1799, Phineas Pratt of Ivoryton, Connecticut, a deacon, silversmith, and inventor, received a patent for a “machine for making combs.” Combs in the late eighteenth century were usually made of cow or ox horn and cut by hand—a slow, labor-intensive process. Pratt’s mechanized invention led to its application to ivory and the development of the comb and ivory cutting industry along the Falls River in Deep River and Ivoryton, which was then known as West Centerbrook.

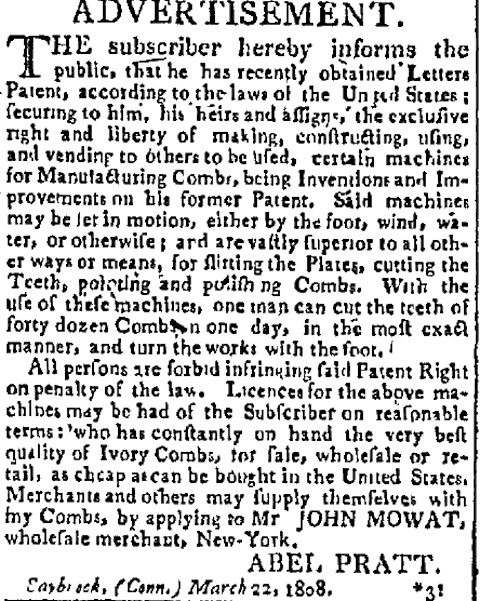

The “machine” (a circular saw) could be run by means of “the foot, wind, water or otherwise” and greatly reduced the time it took to cut the teeth, point, and polish a comb. An 1808 newspaper advertisement placed by Abel Pratt, Phineas’s son, in the Connecticut Herald proclaimed that with this patented machine “one man can cut the teeth of forty dozen combs in one day.” This type of economy of scale allowed for direct competition with British imports and a number of shops sprang up along the mouth of the Connecticut River in the Potapaug Quarter of the Saybrook Colony. Over time, as the process was refined and the industry grew and consolidated, the local workforce applied their ivory cutting skills to other products—including piano keys and billiard balls—at companies such as Comstock, Cheney and Pratt, Reed. At the height of production, 90 percent of the ivory imported into the United States was processed in Deep River and Ivoryton.