By Jesse Nasta

During the early 19th century, free African Americans formed Connecticut’s first independent Black churches, neighborhoods, and associations. One of the earliest and most politically active free Black neighborhoods in Connecticut emerged in Middletown in the late 1820s. Now called the Leverett Beman Historic District—or, more commonly, the Beman Triangle—this small yet activist community sustained one of the state’s first Black churches (the Cross Street A.M.E. Zion Church), formed some of the earliest African American antislavery societies, served as a stop on the Underground Railroad, and became a center of free Black homeownership. Although the Beman Triangle became a largely white neighborhood by the 1930s, the Triangle and its closely associated Cross Street A.M.E. Zion Church remain as testaments to centuries of Black freedom and resilience in Connecticut.

Connecticut Slavery, Emancipation, and the Origins of the Beman Triangle, 1650-1829

Cross Street A.M.E. Zion Church from City of Middletown Architectural Inventory Survey, 1978 – University of Connecticut

By the 1770s, just over 200 Africans and African Americans, nearly all enslaved, lived and forcibly worked in Middletown. Half a century later, the size of Middletown’s Black population remained roughly the same but nearly all had gained freedom. They did so under Connecticut’s 1784 Gradual Abolition Act and through their own efforts to seize freedom—some purchasing themselves and their families out of slavery while others gained freedom by fighting in the American Revolution.

By the early 1800s, New England’s free African Americans were numerous enough and had gained enough of an economic foothold to form their own institutions and property-owning neighborhoods. Middletown’s free people of color established their first church and neighborhood on and near the Beman Triangle in the 1820s.

In 1823, 21 free African Americans formed the second African Methodist Episcopal Zion (A.M.E. Zion) church in Connecticut, the present-day Cross Street A.M.E. Zion Church. (The first African Methodist Episcopal Zion church, Varick Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church, began in New Haven in 1818). In 1828, the A.M.E. church-leading Jeffrey family became the first people of color to buy property on what is now known as the Beman Triangle, just west of what became Wesleyan University three years later. Asa and Elizabeth Jeffrey and their son and daughter-in-law, George W. and Mary Ann Jeffrey, bought adjoining land on the corner of Cross Street and Swamp Street (now Knowles Avenue). Asa and George served as trustees of the newly formed A.M.E. Zion congregation and were instrumental in building the group’s first church structure in 1829, on the Cross Street hilltop just up the street from the Beman Triangle. This emerging African American neighborhood and church soon became centers of the antislavery movement.

The Beman Triangle and Abolitionism

The immediate abolitionist movement—which insisted on slavery’s immediate rather than gradual end—exploded in the late 1820s and early 1830s, the same years when the Beman Triangle and Cross Street A.M.E. Zion Church developed. Reverend Jehiel Beman, one of New England’s leading Black abolitionists, became the Cross Street A.M.E. Zion Church’s first regular pastor in 1830.

Reverend Beman came from Colchester, Connecticut, where his father, Caesar, gained freedom by fighting in the American Revolution in place of his enslaver. Reverend Beman wrote that his father “had always loathed slavery, and wanted to be a man; hence he adopted the name, Be-man.” Carrying this determination for freedom and dignity into the next generation, Beman’s entire family shared his lifelong, intergenerational dedication to freedom and equality. The Bemans remained community pillars and activists in Middletown for three generations and almost ninety years.

Under the Bemans’ leadership, Middletown’s African American neighborhood and church played a national role in the abolitionist movement. In 1834, Nancy and Clarissa Beman, wife and daughter-in-law of Reverend Jehiel Beman, co-founded the “Colored Females’ Anti-Slavery Society of Middletown,” one of the first Black women’s abolitionist societies. The Cross Street A.M.E. Zion Church also hosted prominent abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass and served as a stop on the Underground Railroad. In 1854, Reverend Jehiel Beman openly defied the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act by writing in a public letter to Douglass, “The Underground Railroad…is in good repair, and our office is open for business in our line at all hours, either day or night.” These actions helped reinforce the A.M.E. Zion denomination’s nickname, the “Freedom Church.”

The Beman Triangle and the Significance of Black Property Ownership

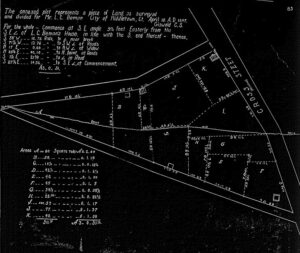

Neighborhood plot and survey, drawn for L. S. Beman, April 10, 1847 – Middletown Town Clerk’s Office, Middletown, CT

For Black community leaders like the Bemans, protesting southern slavery and combating northern white supremacy went hand in hand. Although the North largely ended slavery by the 1830s, free African Americans remained prohibited from voting in some northern states, excluded from most occupations, and subjected to racist threats and even mob attacks. During this time, the Connecticut Constitution of 1818, for instance, limited voting rights to white men and the highly influential American Colonization Society sought to deport free African Americans to Liberia rather than acknowledge their equal right to US citizenship.

In this context, the Bemans and other free Black activists advocated for Black education, temperance (avoiding all alcohol), and property ownership—both to improve the lives of their community members and to counter the prevailing racial caste system. As one Black leader from Connecticut, Reverend Elymus P. Rogers, asserted in 1849, “We must do as other citizens do; and pursue the same paths of respectability. Property is every where respected in this country.” This Black political vision helped motivate the Beman Triangle’s development.

The Beman family, likewise, viewed property ownership as key to African American freedom, respectability, equality, and self-determination. The Beman Triangle’s Black-owned land and houses embodied that goal. In 1846, Leverett Beman (one of Reverend Jehiel Beman’s sons) bought most of the Triangle from Mary Ann Jeffrey (Leverett’s sister-in-law), who was about to lose the land to debt after her husband, George, died. Bounded on the south by Cross Street, on the east by Vine Street (formerly Park Street), and on the west by Knowles Avenue (formerly Swamp Street), this three-and-a-half acre, triangular piece of land came to be known as the Beman Triangle in recent decades because it was Leverett Beman who surveyed and divided it into eleven small house lots. Beman and two other families of color—the Jeffrey and Brooks families—already owned five of the lots. In selling the remaining six lots to other free African Americans, all leaders in Middletown’s A.M.E. Zion Church, Beman created a remarkable African American neighborhood.

Although African Americans bought property and formed neighborhoods throughout the pre-Civil War North, some as close to Middletown as Little Liberia in Bridgeport and Jail Hill in Norwich, the Beman Triangle stands out for being highly organized and entirely Black-owned once Beman sold the remaining lots in 1847. Pre-Civil War neighborhoods consisting entirely of Black residents who owned their own homes were extremely rare and the Beman Triangle is a unique example of this.

At the same time, the exclusion from educational and employment opportunities faced by most African Americans, and their resulting financial hardships, made for constant struggle. Beginning in the 1870s, white residents gradually purchased all the houses on the Triangle as most of Middletown’s African Americans moved away to pursue economic survival and opportunity.

The Decline of the Beman Triangle, 1870s-1930s

The Civil War and Reconstruction brought dramatic legal victories for Black freedom and equality, in Connecticut and nationally. The United States Army won the Civil War in 1865 with the help of 180,000 Black troops, including several Beman Triangle residents. The resulting 13th Amendment to the Constitution realized the Bemans’ decades-long dream by outlawing slavery and involuntary servitude and the 15th Amendment finally granted Black men the right to vote. Yet economic inequality persisted and, in some ways, even worsened for northern African Americans.

A small Black middle class did prosper in post-Civil War Connecticut, but paths to economic advancement narrowed as nearly all African Americans were shut out of the emerging industrial economy. Factory owners, instead, hired large numbers of European immigrants who poured into the United States. Middletown’s Black population reached an all-time low of 57 in 1920 as younger generations of African Americans moved to larger cities. During the 1920s and 1930s, the few remaining, aging Black property owners on the Beman Triangle sold their homes to working-class whites, mostly immigrants from Poland, Italy, and Sweden. By the late 1930s, only the Cross Street A.M.E. Zion Church—which moved to the Triangle in 1921 after Wesleyan University purchased the original church site—remained as a direct link to the former property-owning, antislavery Black neighborhood.

The Beman Triangle Today

Today, a coalition of historians, historic preservationists, and other community members is working to honor and preserve the Beman Triangle. This group includes the Middlesex County Historical Society, the Cross Street A.M.E. Zion Church, the City of Middletown, Wesleyan University, the Connecticut Freedom Trail, and the Connecticut State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO).

The Beman Triangle is remarkably intact, adding greatly to the neighborhood’s historical value and significance. Eight houses owned by African Americans in the 1800s and very early 1900s remain—more than half of the 15 houses that have stood on the Beman Triangle. The surviving historic Black houses are numbers 5, 7, 9, 11, and 19 Vine Street, numbers 8 and 118 Knowles Avenue, and 170 Cross Street. Wesleyan University owns all but one house on the Beman Triangle, having bought most of them in the 1980s and 1990s as the campus expanded to the west.

Although the Beman Triangle (officially the Leverett Beman Historic District) has been on the Connecticut Freedom Trail and the Connecticut State Register of Historic Places since the 1990s, the neighborhood has not yet been placed on the National Register of Historic Places. With support from the City of Middletown and cooperation from Wesleyan University, the Middlesex County Historical Society is working to further commemorate the Beman Triangle.

Jesse Nasta, PhD, is a professor in Wesleyan University’s Department of African American Studies and Executive Director of the Middlesex County Historical Society. He began researching the Beman Triangle as a Wesleyan University student in 2006 and is writing a book about this remarkable neighborhood and its regional, national, and global connections to 19th-century Black community and antislavery networks.