By Diane Dolbashian

In 1918, the Connecticut Board of Education assigned Lewis Sprague Mills to lead a small committee that would prepare a school pamphlet on the state’s history. Mills ended up taking on the task himself and over the next twelve years, he composed what became a four hundred page sixth-grade schoolbook titled The Story of Connecticut.

Using a breadth of resources, Mills turned to libraries, museums, historical societies, university professors, state newspapers, educators, and knowledge keepers for his research. First published in 1932 by Charles Scribner’s Sons, with an expanded 3rd edition in 1943, The Story of Connecticut’s use continued in Connecticut schools through its 5th and final edition in 1958. Today, the book is itself a historical artifact—a window into how it instructed children to understand their state’s past.

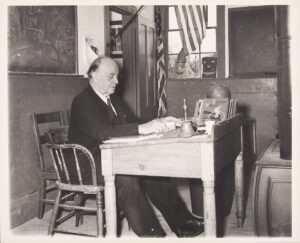

The Author: Lewis Sprague Mills

Lewis S. Mills at the Quasset School in Woodstock, Connecticut, 1954. – By Lewis Sprague Mills, Connecticut State Library. No known copyright.

Writing a history of Connecticut for schoolchildren was a labor of love for Mills. With family roots dating to 17th century Connecticut, the author cherished his home state and believed deeply in the educational mission. In boyhood, the work demands of the family farm frequently kept Mills from attending school. Yet over time he persevered, earning a Bachelor of Science in Education and a master’s degree from Columbia University in 1908 and 1912.

As a young teacher in training, Mills formulated ideas that diverged from established methods. He believed in teaching “from the viewpoint of the pupil” rather than the teacher and in allowing students to ask questions and have discussions. Later, he incorporated this approach into The Story as “Suggestions for Study,” a section at the end of each chapter intended to deepen understanding and promote reflection. For example, students were encouraged to recite poetry, draw maps, and put on plays, among other activities. Through The Story of Connecticut, Mills helped define the state’s history curriculum during the first half of the 20th century.

Contents of the Textbook

Lewis S. Mills reading to a group of children at Quasset School in Woodstock, Connecticut in 1954. – By Lewis Sprague Mills, Connecticut State Library. No known copyright.

At around four hundred pages, The Story of Connecticut contains hundreds of years of state history spanning across a multitude of topics. The Story opens with Adriaen Block’s “discovery” of Connecticut and his river voyage to Hartford in the early 17th century. A second chapter examines the state’s geological formation, tracing physical changes over millennia, while a third offers an overview of the natural resources that shape the contours of Connecticut’s varied landscapes.

From there, Connecticut’s colonial phase branches into two main narratives that occupy more than half of the book. One concerns the Indigenous peoples of southern New England’s woodlands, their cultures, and their response to the arrival of European settlers. Drawing from the work of both Native and non-Native people, Mills consulted with anthropologist Frank G. Speck, Mohegan Medicine Woman Gladys Tantaquidgeon, and other Native people in Connecticut. The book features the Pequot, Mohegan, Narragansett, Wampanoag, and other Tribes in a sweeping chronicle of wars and alliances as well as daily life and cultural practices. Driving the other narrative branch are the themes of heroism, bravery, and resilience of the Connecticut settlers and how they struggled to establish dominance over their environment as well as their adversaries. At the same time, Mills did not avoid describing how white settlers violently displaced Indigenous people from their territories.

From 1689 to 1945, war is the engine that moves history forward in The Story of Connecticut. Several chapters relate Connecticut’s part in national and international conflicts: the French and Indian Wars, the first Spanish Wars, the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, and World War II. While touching just barely on the topic of race relations, a chapter on “Slavery and the Civil War” attempts to give an honest telling of the slave trade and enslavement in Connecticut from 1619 to the Civil War. This is a panoramic history, viewed from the top down and cloaked in glory. It names the battlefields, heroes, military leaders, and heads of state, but takes no real account of the individual lives of soldiers or their families on the home front.

In later editions, Mills added topics and sections to expand the teaching of Connecticut’s history. A departure from the rest of the book’s heroic tone, Mills included a chapter on the mostly unseen members of Connecticut’s society. Titled “Homes for Unfortunate People,” it describes facilities that house the poor and the mentally ill, criminals, veterans, and orphans, as well as “other institutions for unfortunate people.” Mostly descriptive of the various institutions and their roles, Mills emphasized the state’s financial support.

While he included critiques of settler colonialism, Mills wanted to impart a sense of national patriotism and civic pride to students. In addition to Connecticut’s wartime contributions, he aimed to distill three hundred years of progress into the book’s remaining chapters about the state’s achievements in economics, industry, invention, education, literature, urban development, and infrastructure.

How does The Story of Connecticut compare to how history is taught today?

Lewis S. Mills and students, grades 5-8, outside the Plainfield Academy building in 1903. – By Lewis Sprague Mills, Connecticut State Library. No known copyright.

The Story of Connecticut was intended to be more than just a compilation of facts. It was a plea to children to assign the highest value to their freedom and to the stories that laid the foundation for that freedom.

To a certain extent, The Story of Connecticut aspires to the same goals as the social studies programs taught in Connecticut schools today. In both cases, one purpose is to educate students to become responsible members of society. They ask how the state’s past has shaped its present identity and use an interdisciplinary approach to understand that past. Both today’s students and those growing up in the mid-20th century learn about Connecticut’s role in national history—its people, geography, constitution, government, innovations, and development over time.

The last ten years have marked a significant, state-mandated shift in Connecticut’s social studies programs. Between 2019 and 2022, Connecticut passed various legislation to require public schools to provide courses and content pertaining to African American, Black, Puerto Rican, Latino/a, Native American, and Asian American and Pacific Islander history. While The Story aspires to promote inquiry, it also keeps to traditional historical narratives of the day, colored by notions of nostalgia, patriotism, and courage. Writing against the backdrop of two world wars and a shattering economic depression, Mills naturally aligned his work with such themes. Mills wrote The Story of Connecticut because he believed that the only pathway to understanding Connecticut’s present—and future—is through its past. Mills’ life and book can now be counted among the historical sources that students and historians can study today.

Diane Dolbashian is a cultural historian and former library director at The Corning Museum of Glass.

Bibliography is available upon request.