John Brown was a staunch abolitionist famous for his beliefs in the equality of African Americans and for his use of violence in opposing the spread of slavery in the decade before the Civil War. Considered by pro-slavery Southerners as “a damned black-hearted villain,” abolitionists met Brown’s radical exploits with a combination of admiration and revulsion.

John Brown was born in Torrington, Connecticut, on May 9, 1800. His father, Owen, having struggled in New England as a tanner and a farmer, moved his family to Hudson, Ohio, in 1805. The Browns followed in the footsteps of other Connecticut Calvinists who took advantage of opportunities for expansion on Ohio’s Western Reserve, a place also known as “New Connecticut.”

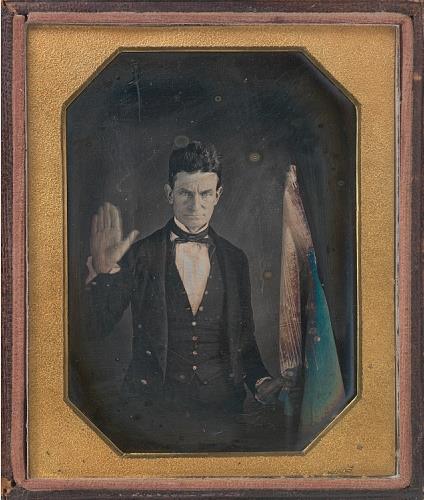

Augustus Washington, John Brown, ca. 1846–1847, Daguerreotype – National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

The demands of Owen Brown’s tannery consumed much of John’s childhood, leaving him little time for formal education. In his free time Brown mixed regularly with the Native Americans living in the Hudson area and learned to appreciate nonwhite cultures. When it came to slavery, his father instilled in him the belief that African Americans not only belonged free, but also deserved a place in white society as equals. It was this deeply held belief that dictated much of Brown’s conduct later in life.

Brown’s professional life consisted of a series of complex and ultimately ruinous business ventures. At different times he worked as a tanner, shepherd, cattle trader, real estate speculator, and wool distributor, but financial setbacks plunged him deeply into debt. By 1850, the failure of a wool distribution company he started with Simon Perkins Jr. involved Brown in a string of lawsuits that monopolized the next several years of his life.

Brown Sets His Sights on Bleeding Kansas

In 1855, shortly after moving his family to North Elba, New York, Brown received word from his sons of atrocities taking place in the Kansas territory. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, which created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska and allowed voters to decide whether they wanted to make slavery legal or illegal in those territories, sparked a flood of migration to the area by both pro-slavery and “Free State” supporters. Each side tried to establish control of the area, and often did so by violent means.

Brown arrived in Kansas convinced he needed to match the brutal methods employed by slavery proponents. On May 24, 1856, he led four of his sons, a son-in-law, and two other men in a raid on pro-slavery settlers along Pottawatomie Creek. Brown dragged his intended targets out of their homes in the middle of the night to a predetermined location where his cohorts cut them down with swords. In total, Brown’s party killed five pro-slavery men in what came to be known as the Pottawatomie Massacre.

Brown, convinced of the justness of his cause, did not see himself as a murderer, but instead as a dispenser of God’s justice. The religious fervor he brought to his crusade inspired a fanatical following. He stirred clergymen like Theodore Parker to declare with extreme conviction that slaves had the right to revolt and freemen the right aid them and kill all who opposed them.

The Raid on Harper’s Ferry

In 1856, Brown decided to travel back East and raise funds for his most audacious plan, a raid on the federal armory in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. He intended to confiscate the weapons from the armory, move into the countryside and free enslaved people from the surrounding area, who, once armed, would retreat with Brown’s men back into the Appalachian Mountains for protection. Once safely in the mountains, Brown intended to establish an independent mountain colony of Black people, as well as a base from which to coordinate future attacks.

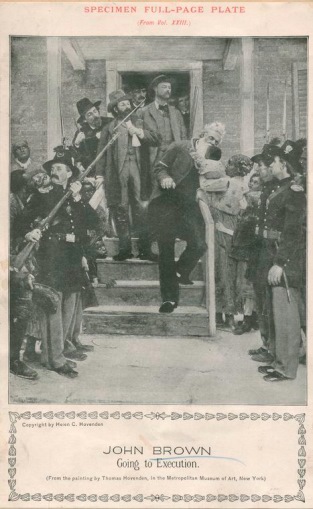

John Brown. Going to Execution. – New York Public Library Digital Collections, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs

Brown launched his raid on October 16, 1859, with nineteen men. He met with little resistance in the beginning, capturing the armory without a fight. Brown then chose to stay and wait for a groundswell of support from newly freed people, but that support never came. As word spread of Brown’s raid, local militias and angry citizens converged and fired on Brown’s position in the engine house at Harper’s Ferry. President James Buchanan then sent federal troops under Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee to end the standoff. Brown tried several times to negotiate for his freedom and refused to surrender, forcing an eventual storming of his position that brought the raid to an end on its third day.

Brown’s attack on Harper’s Ferry created a panic in the slave-holding South as apprehensions about further attacks promoted a military buildup and intensified secessionist feelings among Southern residents. Brown’s actions had a national impact in the political arena as well. Southern Democrats attributed the raid to the “Black Republican” Party of the North. For their part, Republicans scrambled to disassociate themselves from Brown and the controversial raid. Through the moral, political, and religious conflict he created among both abolitionist and pro-slavery factions in America, Brown managed to polarize the nation in a way unique to any man of his time.

Despite the loss of life at Harper’s Ferry (including two of Brown’s sons), Brown always believed his actions just. The Virginia courts saw it otherwise, however. They tried him on three counts: conspiracy to incite a slave insurrection, treason against the state of Virginia, and first-degree murder. It took a jury only forty-five minutes to find Brown guilty and on December 2, 1859, officials hanged Brown for his offenses.