By Christine Adams

According to the National Gallery of Art, as well as art historians all over the country, the artists known as the “Border Limner,” the “Kent Limner,” and Ammi Phillips are one in the same—one of the most important and prolific folk portraitists in 19th-century America. It took over a century, however, for numerous people to put together all the pieces and solve the mystery of Ammi Phillips’s identity.

Ammi Phillips and 19th Century Kent

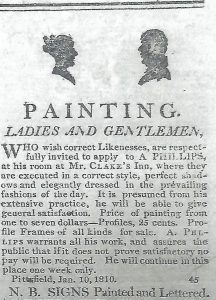

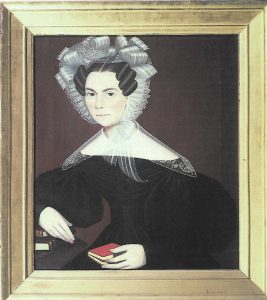

The work of American portraitist—or “limner”—Ammi Phillips illuminates the role of women in society and culture, but not in ways that are straightforward or expected. From 1829 to 1838, Phillips lived and painted in the area around Kent, Connecticut. He even rented a nearby tavern from where he advertised his ability to paint his people with “correct likenesses,” and “perfect shadows…elegantly dressed in the prevailing fashions of the day.” Mary Black, former director at the Museum of American Folk Art, argued that while in Kent, Phillips “developed the formula for the graceful forward-leaning ladies of the period.” Most of his works, however, were unsigned.

During the Victorian period, despite Phillips’s “sophisticated and penetrating portraits reminiscent of the 15th Century Florentines,” his folk art fell out of fashion, often relegated to attics. Art critics of the day developed condescending terms to describe folk art and devalued the genre with descriptions such as naïve, plain, rural, provincial, idiosyncratic, and nonacademic. Phillips’s work (along with that of other itinerant limners) collected dust in familial storage and the identities of his subjects were often lost. As time passed, his unsigned paintings became disconnected from the artist—attributed to an unknown “Kent Limner” or “Border Limner” (the name derived from his portraits done in communities near the New York/Massachusetts border).

Identifying the “Kent Limner”

The identity of the “Kent Limner” began to take shape when an art-minded couple, George Laurence and Helen Redgrave Nelson, moved to Kent in 1894 on the rising swell of the modern art movement. Laurence was an acclaimed artist and Helen was an art critic for the New York Globe. With affordable rooms for studios, Kent provided a bucolic and aesthetically pleasing home for artists at the time.

A synergy between modern and folk art created a widespread appreciation of their similarities— with both periods containing bold colors and a sharp contrast between light and dark. Intimately aware of these similarities, in 1924, Helen Nelson arranged a Kent street fair highlighting seven of Phillips’s works—all coaxed from her neighbors’ attics and parlors. The result was a startling public recognition that these portraits were created by the same hand—a mysterious painter dubbed “the Kent Limner.”

Yet Phillips’s identity and respective art were regarded individually until the curiosity and admiration of Barbara and Lawrence Holdridge lead to a groundbreaking discovery in 1959—that Ammi Phillips created the enormous body of work once credited to three separate unknown artists. The Holdridges’ discovery was Herculean, precipitated by Barbara’s purchase of Phillips’s 1840 portrait of George C. Sunderland. Barbara and Larry spent decades researching the work and others like it. The Holdridges then convinced Mary Black—then director of the American Folk Art Museum in New York—that the trifecta of aliases belonged to one portrait artist: Ammi Phillips. The Holdridges’ research on the Kent Limner, the Border Limner, and Ammi Phillips culminated in Barbara’s book, Ammi Phillips: Portrait Painter, 1788-1865. In 1994, Stacey Hollander, who took over as director of the American Museum of Folk Art, revisited 50 years of Ammi Phillips’s portraiture, building on the strong foundation of scholarship begun by the Holdridges.

Identifying Phillips’ Subjects

Almira Lucretia (Mills) Adams Perry – One of Ammi Phillips’s “forward-leaning women” – Courtesy of the Kent Historical Society from a private collector

Decades later, the historiography of Ammi Phillips continued with Kent Historical Society Trustee, genealogist, and house historian, Melanie Marks. While members of the Kent community had collaboratively uncovered Ammi Phillips’s identity, the identities of his subjects—such as the “forward-leaning women”—required well-honed research to discover.

In the 19th century, the women Phillips painted were not allowed to own real property, therefore it became commonplace for fathers to bequeath furniture to their daughters—including paintings. When those daughters married, however, their property compulsorily became their husband’s. Therefore, “maiden names became further and further from the family’s consciousness,” as did the identities of many Phillips’s portrait sitters, male and female alike.

Collaborating with both Barbara Holdridge and Ammi Phillips-scholar David Allaway, Melanie Marks began tracking down the identities of Phillips’s sitters. In her research, she discovered that the subjects of several portraits often came from the same family. Marks subsequently attributed more than 600 paintings to Phillips as Allaway acknowledged the regularity with which inquiries about Phillips came not from art historians but genealogists wishing to “replace the anonymous silhouettes on their family trees with a likeness of their ancestor.”

One woman, Helen Nelson, began a daisy chain of events in art history that eventually led to not only the reincarnation of the lost identity of the “Kent Limner,” but also hundreds of the subjects he painted. These curious and tireless women—Nelson, Holdridge, Black, Hollander, and Marks—were instrumental in shining a metaphoric light on seemingly dust-laden family portraits—master works of a self-taught limner. Once obscured due to a repressive pretense toward folk art and the legal and societal suppression of women’s property rights, these brilliant portraits are now in their right and justified place—well installed in the annals of art history and included in their rightful family albums.

Christine Adams serves on the Board of Trustees for the Kent Historical Society. A resident of New Preston, she is the author of an anthology of poetry and also works as a researcher for the Gunn Historical Museum.