By Patrick J. Mahoney

Oftentimes, the historical narrative of the American Revolution is oversimplified, appearing devoid of its many sociopolitical complexities. One area in which this is certainly the case, is the lack of consideration given to the tens of thousands of Americans who remained opposed to the actions and ideals of the independence movement. Labeled by their American Whig or patriotic counterparts as “Tories,” such individuals brandished themselves with the name “Loyalists,” for their unyielding support of the colonies’ political relationship with Britain.

At the outbreak of the war, Connecticut consisted of six counties and 72 townships. According to the census of 1774, throughout these counties and townships, there existed some 25,000 males between the ages of 16 and 50, of whom about 2,000 identified themselves as Tories. Nowhere was the presence of these individuals stronger than in the southwestern portion of the state, particularly in Fairfield County.

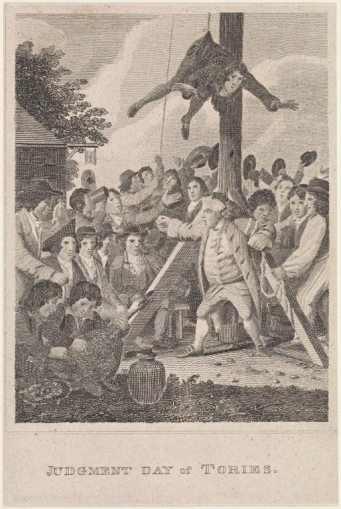

Judgment Day of Tories, engraving, ca. 1790s – By Elkanah Tisdale, New York Public Library Digital Collection. Used through Public Domain.

Religion and Royal Allegiance

Within colonial Connecticut, the roots of Toryism, and the specific localities in which Loyalist sentiment became most prevalent, were often directly related to the religious affiliations of the population. Unlike their Episcopalian counterparts in the American South who were, by that time, more firmly established and often apt to embrace the patriotic sentiments of their communities, the Episcopalian clergymen of Connecticut were fervent in their support for king and country. The reasoning behind such differences in civic loyalties can perhaps be explained by the funding and mission of the church in the Northeast.

Whereas the southern Episcopacy drew the majority of their funds from the population to whom they ministered, the Connecticut variants were stipendiaries of the English Missionary Society. As such, they viewed it as their duty to pray for, and show deference to, their “Most gracious Sovereign Lord, King George, and the Royal Family.”

Anti-Tory Laws

The presence of Loyalists was such that, by the winter of 1775, the General Assembly passed an “act for restraining and punishing persons who are inimical to the Liberties of this and the rest of the United Colonies.” The piece went on to note that “any person by writing, or speaking, or by any overt act, shall libel or defame any of the resolves of the Honorable Congress of the United Colonies, or the acts of the General Assembly of this Colony…shall be disarmed and not allowed to have or keep any arms, and rendered incapable to hold or serve in any office civil or military, and shall be further punished by fine, imprisonment or disfranchisement.”

After the Continental Congress declared independence in July of 1776, further legal action came against potential Tories on the state level. In October of that year, one such act stated that any person found aiding or abetting the British, whether by recruitment, military service, intelligence gathering, or acts of conspiracy, was to be charged with high treason and put to death. Throughout the war authorities convicted six individuals of high treason under this act, but only one, Moses Dunbar of Waterbury, was actually put to death.

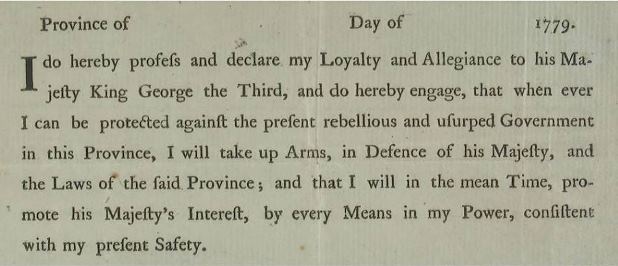

British loyalty oath, administered during the American Revolution, 1779 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain.

Further legislation put forward in the following year stated that in order to purchase, hold, or transfer any real estate, one needed to first take an oath of fidelity to the state. Additionally, a committee of inspection, set up for this purpose, had the power to remove and confine any individuals rightfully deemed to be “inimical and dangerous to the United States.”

New-Gate Prison: “The Catacomb of Connecticut”

One of the intriguing elements of the Loyalist story in Connecticut is the infamous prison in which many of the most prominent Loyalists found themselves confined during the war effort. Originally a copper mine with origins dating back to the 1730s, the colonial legislature approached John Viets, whose land the old mine was a part of, and proposed that given the need for a space to confine Loyalists, the mine might once again prove to be a profitable commodity to its current owner.

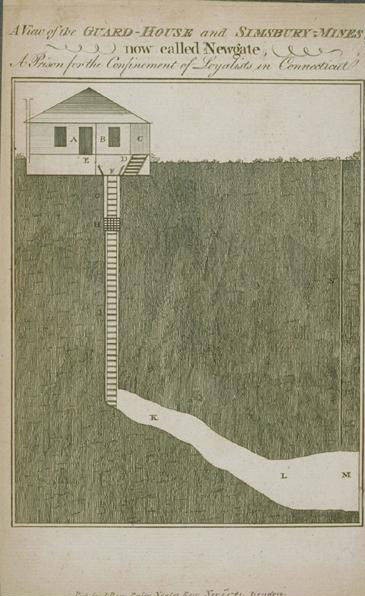

A view of the guard-house and Simsbury-mines, now called Newgate – a prison for the confinement of Loyalists in Connecticut – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain.

Viets set about making renovations to the old mine, constructing a guardhouse over the main shaft, and adding iron bars to thwart the possibility of escape. The infamous Loyalist minister and author of the General History of Connecticut, the Rev. Samuel Peters, who had himself fled to England following intimidation for his political stances, described the finished mine turned prison as such: “Here are copper mines. In working one many years ago, the miners bored half a mile through the mountain, making large cells 40 yards below the surface, which now serve as a prison, by order of the General assembly, for such offenders as they chuse (sic) not to hang. The prisoners are let down on a windlass into this dismal cavern, through a hole, which answers the triple purpose of conveying them food, air, and – I was going to say light, but it scarcely reaches them. In a few months the prisoners are released by death and the colony rejoices in her great ‘humanity’ and the ‘mildness’ of her laws. This conclave of spirits imprisoned may be called, with great propriety, the Catacomb of Connecticut.”

While New-Gate remains the most notorious prison of the era, it was hardly the only institution to house Tory captives. It was said that nearly every jail in the colony held a number of political prisoners, and such was the reputation for prison discipline, that throughout the war effort, Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey all sought to send their prominent Tories to face imprisonment in Connecticut. Three such prisoners were Governor Franklin and Mayor Matthews, from New Jersey and New York City, and one Dr. Benjamin Church of Watertown, Massachusetts. The latter individual arrested directly by George Washington for his aide of British troops in Boston.

The Fate of Tories as the Tide of the War Turns

As critical colonial victories began changing the course of the war in the summer of 1777, the governor of Connecticut issued a proclamation, in accordance with the Assembly, which assured a pardon to any individuals convicted of treasonous activity. To avail of such a reprieve, however, the individual had to present himself or herself in Connecticut before a justice of the peace and swear an oath of allegiance. By the close of the war, a large proportion of the state’s Tories took the oath (recanting their earlier political allegiances to the crown) and settled back in to their respective communities. Many who had missed the date of amnesty, however, either as a result of having left the colony earlier in the war, or having taken up arms in the service of the British army, never received pardons.

Benjamin West, John Eardley Wilmot, 1812, oil on canvas – Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. Used through Public Domain.

A painting by Benjamin West, himself an American expatriate who spent much of his adult life in London, helped perpetuate a myth that many such individuals returned to England at the war’s end. The majority of the 100,000 Loyalists who relocated at the conclusion of the conflict set their sights closer, however, settling not in England but in Canada. This trend certainly proved true with the outstanding Connecticut Tories. In various towns throughout the state, residents came together to vote on whether their Loyalist neighbors should be allowed to return and resettle within the given community. In many cases, the residents of Connecticut decided against such a course of action, leaving the Tories with little choice but to relocate. In most cases, such individuals found refuge in the wilds of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

Patrick J. Mahoney is a Research Fellow in History & Culture at Drew University and former Fulbright scholar at the National University of Ireland Galway