By Edward T. Howe

On June 1, 1819, Governor Oliver Wolcott Jr. approved a legislative charter for the Society for Savings in Hartford—the first mutual savings bank in the state. Philanthropic businessmen organized the bank to help the working class set aside funds for their financial needs—it lasted almost 175 years before a merger in 1992.

Founding the Bank

Sidney W. Crofut in his office, Society for Savings, 31 Pratt Street, Hartford – Connecticut Historical Society

Historically, the first non-charitable mutual savings banks appeared in England and Scotland between 1804 and 1814. In the United States, the Provident Institution for Savings in Boston became the first state-chartered mutual savings bank in 1816. Two years later, the Salem Savings Bank and the Savings Bank of Baltimore opened in Massachusetts and Maryland, respectively. In 1819, similar firms appeared around the East Coast in New York, Newport, Providence, Portland, and Hartford.

A group of Hartford philanthropic business leaders—wealthy through commercial, financial, and professional activities—received a charter from the General Assembly for “The Society for Savings” in May 1819; Governor Oliver Wolcott Jr. approved the charter on June 1st. In an effort to help workers with limited financial resources provide for future needs, Article I of the by-laws stated that the “primary objects of this institution are to aid the industrious, economical and worthy; to protect them from the extravagance of the profligate, the snares of the vicious, and to bless them with competency, respectability and happiness.” The founding 41 uncompensated corporators had the power to choose trustees, a president, vice-president, secretary, and treasurer (who received a salary after the first year because of extensive duties) to serve one-year terms with possible reappointment. Given the unwieldy corporate body, seven of them—including one of the officers—could form a quorum for business purposes.

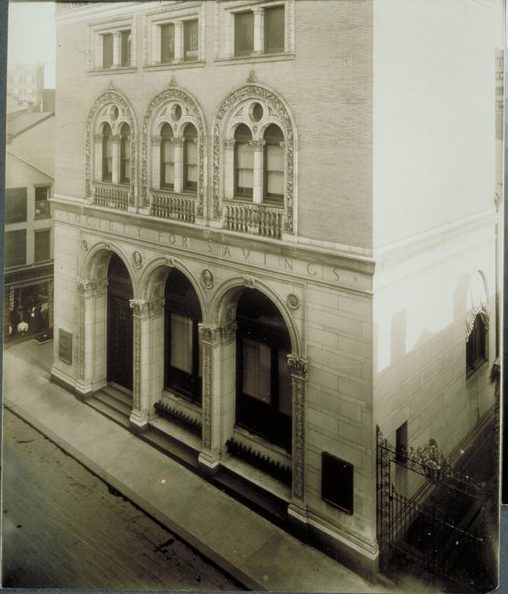

The bank—only open on Wednesdays from two to five pm, supposedly to save expenses—conducted business in various places after its inception. By 1834, it finally had a permanent location on Pratt Street—where it remained throughout its existence.

Bank Business

The bank authorized individual deposits of up to two hundred dollars annually, but a depositor had to give four months advance notice in writing for any withdrawal. During the first few months, deposits quickly grew from $532 on July 14 (opening day) to $4,227.59 (before interest) by December 1. The bank paid yearly dividends of five percent from 1819 to 1835, with varying rates thereafter. The bank, required by its charter, made an annual report about its deposits and dividends to the General Assembly.

The bank could make authorized loans from its deposits, consistent with state laws. The General Assembly clarified the vaguely worded provision in 1821, granting the bank the right to invest in bank stocks and, in 1833, granting the right to make real estate investments.

Since it was a “mutual” savings bank, the depositors had to share any losses or profits “in just proportion.” Moreover, depositors had no voting rights as the bank was not a publicly traded entity that could issue common stock. In 1984, however, the bank decided to convert to a publicly traded stock company.

Although the bank survived for almost 175 years through varying economic cycles of prosperity and decline, it eventually met its demise. On August 31, 1992, the Society for Savings, burdened with bad commercial loans, agreed to be acquired by Bank of Boston.

Edward T. Howe, Ph.D., is Professor of Economics, Emeritus, at Siena College near Albany, N.Y.