By Edward T. Howe

Connecticut pocketknife production began around 1840. Over the next two decades, Connecticut became the earliest state to have a burgeoning craft. Located mainly in or near the western Naugatuck Valley, the firms had the benefit of abundant water supplies, skilled metalworkers (mainly from Sheffield, England), transportation modes to population centers, marketing distribution channels, and sustainable demand. Challenging economic conditions in the first half of the 20th century, however, led to the demise of a once leading craft by 1955.

Pocketknife Manufacture Before 1800

Historians have traced the earliest folding pocketknives to pre-Roman Spain. These knives were made of iron, perhaps as early as 600 B.C. They also appeared in the Roman era from the 1st to the 5th centuries, often with iron blades and bronze handles and, later, among the Vikings from the 8th to the 11th centuries. These original pocketknives–known as peasant knives for their varied uses (e.g., cutting food and weaponry)–lacked a spring-back mechanism to hold the blade in open or closed position. This same type of knife, made of carbon steel, later made its appearance in Sheffield, England, around 1650, with a slip-joint (non-locking folding knife) version by 1660.

Although by the late 18th century Americans were making small folding penknives of steel for sharpening quill pens for writing, other types of folding pocketknives were still imported from Sheffield. Unknown workers in New England had been making pocketknives in small shops in the early decades of the 19th century, but lacked specialized skill and suitable equipment. Besides pocketknives, these small shops also produced buttons, thimbles, tableware, and other metal goods that were sold by roving Yankee peddlers. Known specialized pocketknife makers did not appear in New England, and elsewhere, until around 1830.

Connecticut Pocketknife Craft Emerges and Grows

A 19th-century Connecticut pocketknife was made by skilled craftsmen using tools and equipment that were familiar to English producers. The knives ranged from two to six inches long with one or more hinged blades at one or both ends. The blades were usually forged or blanked from strip steel before being trimmed, hardened, tempered, ground, and cleaned. Metal liners defined its shape and part of the frame, with bolsters attached. The tang, or unsharpened extension of the blade, was attached to the hinge pin of the handle, generally made of bone or wood. The finished knives, once sharpened, then entered distribution. Consumers used them to open various items, prepare food, shape wood, do gardening, and accomplish many other tasks.

American firms specializing in pocketknife manufacturing first appeared around 1829 in both Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Broadmeadow & Company) and Worcester, Massachusetts (Moses L. Morse & Company). Specialized production of pocketknives in Connecticut began several years later, in 1841, with Lyman Bradley & Company in Salem (which later became Naugatuck). Bradley employed skilled workers from Sheffield, England, who were attracted by higher wages and steady employment.

Holley Manufacturing Company, Lakeville (Salisbury) – Connecticut History Illustrated

In 1843 Bradley became manager of a Waterville (Waterbury) firm—which became the Waterville Manufacturing Company by 1847—that started producing pocket knives. Other firms also quickly entered the craft at this time. The Holley Company of Lakeville (part of Salisbury) started production in 1844 and soon became one of the industry’s most prolific producers. Four other firms opened around 1849: the American Knife Company of Plymouth Hollow (which became Thomaston in 1875), Smith & Hopkins (Naugatuck), the Birmingham Knife Works and Clark R. Shelton (both of Derby). While Smith & Hopkins and Shelton appeared to have closed by 1851, from 1850-1900 12 more companies opened in or near the Naugatuck Valley. By this time, the Connecticut firms had become leaders in the craft.

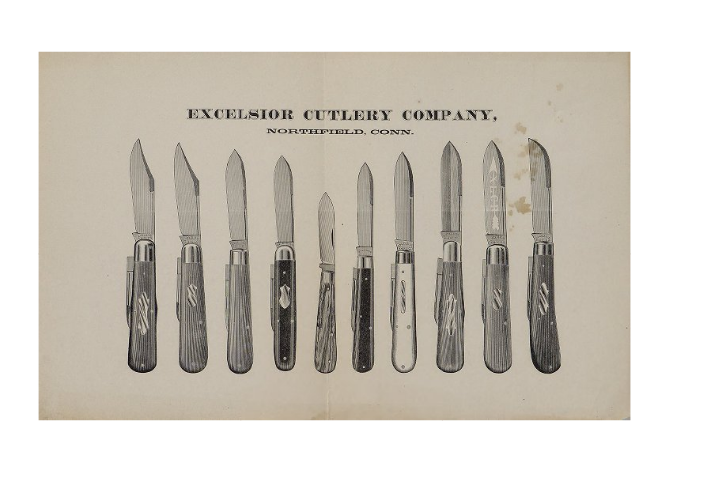

The Holley Manufacturing Company employed up to 85 men and women and had annual sales as high as $50,000 in its best years (leading up to 1900). The Empire firm grew rapidly over the next several decades, such that it employed 50 workers producing about 800 patterns of pocketknives by the end of the 19th century. The Northfield establishment expanded in 1865 by purchasing a factory of the American Knife Company and buying the Excelsior Knife Company (1880-1884) of Torrington. More notably, this company won awards at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876, the Paris World’s Fair in 1878, and the Columbian Exhibition in 1893 in Chicago for its trade-marked “UN-X-LD” pocketknives.

Although the area offered many advantages to these firms–abundant water power, competent management, transportation modes to population centers, and the skilled workers–there remained stiff competition from Sheffield and German producers. To counter foreign competition, William Rockwell of Miller Brothers Cutlery Company of Meriden (1863-1926), and other supporters, helped the American pocketknife industry to expand by persuading Congress to enact tariff legislation.

During the late 19th century, skilled workers in the craft, who had been agitating for higher wages and other benefits for years, finally succeeded in forming a union. The Pen and Pocket Knife Grinders’ and Finishers’ National Union organized on January 1, 1890, with local chapters in Connecticut. The union disbanded in 1917, but the Metal Polishers International Union then absorbed most of its membership. However, it appears that unskilled workers–men and women–were not unionized.

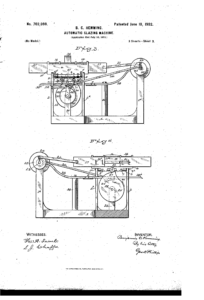

Detail from patent for Benjamin Hemming’s automatic glazing machine. Patented June 10, 1902. U.S. Patent Office

20th Century: Demise of the Connecticut Firms

The decline of the Connecticut pocketknife industry actually began in the last two decades of the 19th century, when six of the 17 remaining firms went out of business. Competitive conditions for the Connecticut firms further intensified from 1900-1930. They faced additional firms in the US market as the aforementioned tariffs led to a drastic decline in European imports, which all but ceased during World War I. Before the conflict, tariffs encouraged skilled Europeans to migrate to America, but the supply of labor declined with wartime casualties. Connecticut firms also grappled with the gradual mechanization of production processes. For example, Benjamin Hemming of Meriden received a patent in 1902 for an automatic glazing machine that proved especially useful for grinding knife blades. As increasing numbers of skilled workers retired after the war, the firms accelerated mechanization of their processes.

Among the firms that left the Connecticut market were: the Southington Cutlery Company (1867-1905), which converted to a hardware business; the American Knife Company of Thomaston, which closed in 1911; and three producers (Waterville and American Shear in 1911 and Northfield in 1919) that were sold to the Clark Brothers Cutlery Company of Kansas City, Missouri. Two major weapons makers, however, entered the industry. The Winchester Repeating Arms Company of New Haven and the Remington Arms Company of Bridgeport began pocketknife production in 1919 and 1920, respectively, to offset a decline in revenue after World War I ended.

The demise of the craft occurred over the next two decades. The Great Depression claimed the Empire Knife Company in 1930 and the Meriden Knife Company (1917-1932). Around 1940 Winchester and Remington (controlled by the Dupont Company as of 1933) converted back to arms production as World War II escalated in Europe. The closing of the American Knife Company of Winsted in 1955 marked the end of an era.

Edward T. Howe, Ph.D., is a Professor of Economics, Emeritus, at Siena College near Albany, New York.