By Edward T. Howe

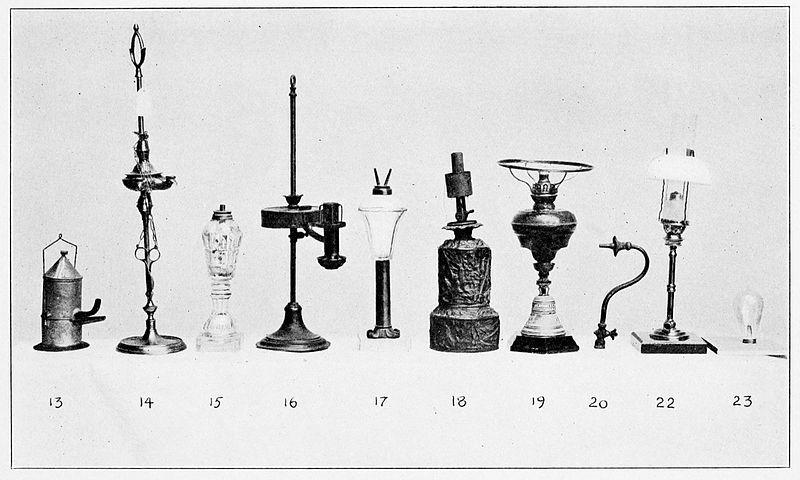

Throughout the 19th century, in a time before gas lamps and incandescent bulbs were more widely embraced, Connecticut firms made oil lamps using various fuels, burners, and different materials. These lamps gained acceptance as their lighting capacity was an improvement over candles, and changes in their shapes, sizes, and colorful designs evolved throughout the period.

Colonial Lighting

When 17th-century English colonists arrived in Connecticut, they relied upon log fires or candlewood (pine or fir knots or splints) burning on the hearth for heating, cooking, and illumination. (For portability, a piece of resinous (tar-emitting) wood could function as a torch.) These early colonists also brought with them a familiar iron oil lamp—the Betty lamp—that had a shallow container with a spout for a wick (porous cloth that drew liquid fuel to a flame), holder, and a hook for hanging. Initially, fish oil or grease was burned, but the smell was odiferous and the light was often unreliable. Nevertheless, American merchants regularly imported Betty lamps or else relied on their production by skilled colonial tradesmen.

In addition, the early colonists may possibly have used a primitive form of candle—the rushlight—consisting of the dry innards of a rush plant soaked in a fatty substance that produced a lot of smoke and little light. More often, 18th-century colonists made tallow candles from animal grease and, later, whale oil. Most tallow candles were fashioned by women in the home, while candle-makers (chandlers) produced these and more expensive candles in larger population areas. More expensive types of candles came from beeswax, bayberries, and spermaceti (a waxy substance from the head of a whale). Unlike tallow candles, spermaceti candles burned longer and cast a brighter light.

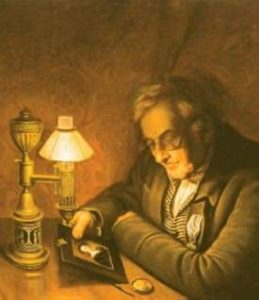

Improved whale oil lamps became popular between 1800 and 1840. They owed their admiration to the discovery of the first scientifically developed lighting device by the Swiss chemist Amie Argand in 1784. His lamp permitted better combustion of oil, relied on a glass chimney for better air flow, and included a device in the burner for raising and lowering the wick. Whale oil lamps were made of tin, pewter, brass, Britannia (a pewter alloy), and glass. They provided greatly improved light with little smoke or odor. However, most homes could afford only the less expensive grades of whale oil.

Oil Lamp Production in Connecticut

Daniel Hayden appears to have made the first brass whale oil lamp in Waterbury while working for Leavenworth, Hayden & Scovill. By the 1840s the Benedict and Burnham Manufacturing Company (1843-1900) was also making brass whale oil lamps in Waterbury. Another firm, Fuller and Smith, made pewter whale oil lamps in New London around 1850. The sale of these lamps was aided by a related development—the invention of the friction match by John Walker, a British chemist, in 1827. It proved to be a major advance in lighting candles and oil lamps.

When prices for whale oil began to increase, those homes with lesser incomes searched for cheaper alternatives. Two fuel sources thus emerged in the 1840s: burning fluids and lard oil. Lard oil lamps became popular after overcoming the problem of the lard solidifying at room temperature. Burning fluid lamps were commonly a mixture of distilled turpentine (camphine) and distilled alcohol. They produced excellent light, but the fluid proved highly combustible. The lamps were made in Connecticut by Edward Miller and Company starting in the early 1840s. Another firm, the Meriden Britannia Company (1852-1898), was known for both burning fluid and lard oil lamps. Both types of lamps remained popular until the wider adoption of kerosene.

Kerosene evolved as the final major fuel for oil lamps during the 1860s. Kerosene, discovered by Abraham Gesner of Canada in 1846 and James Young of Britain in 1848, was originally distilled from coal. Its successful derivation from petroleum, however, resulted in its use as the most efficient fuel for oil lamps. It was also cheap, abundant, light weight, and a safe by-product. Yet, as with all previous types of oil lamps, it required regular maintenance: trimming the wick, checking the fuel level, and cleaning.

Several Connecticut firms made kerosene lamps. In addition to Edward Miller and Company and the Meriden Britannia Company, other firms included the Bristol Brass and Clock Company (1850-1902); the Holmes, Booth, and Haydens Company (1853-1901) of Waterbury; the Bradley and Hubbard Company (1854-1940) of Meriden; the Bridgeport Brass Company (1865-1961); the Plume and Atwood Manufacturing Company (1871-1955) of Waterbury; the Charles Parker Company (1877-1957) of Meriden, which eventually acquired Bradley and Hubbard in 1940; and Meriden’s Handel Lamp Company (1884-1936), known for its hand-painted glass shades.

In addition, several Connecticut companies produced oil burners—the part of the lamp where a match ignited the wick to produce light from the flame. Early whale oil lamp burners were made of pewter but pewter soon gave way to brass, a more corrosion resistant metal. As kerosene lamps became popular, some firms became known for their burners. Among them were the “Novelty” burners made by Plume and Atwood, starting around 1870; the “Lincoln” and “Leader” burners made by the Bridgeport Brass Company after 1875; and the “Queen Anne” burner made by the Scovill Manufacturing Company from the late 1800s to the early 1900s.

During the 19th century, various iterations of oil lamps achieved considerable progress in lighting capability. Nevertheless, oil lamps still required lots of fuel and regular maintenance. Importantly, the amount of light emitted was limited by the surface of the wick. Home and business owners yearning for cheaper lighting spread over a larger radius soon embraced the introduction of gas fixtures and electricity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Edward T. Howe, Ph.D., is Professor of Economics, Emeritus, at Siena College near Albany, N.Y.