By Alec Lurie

When English warships landed at Fairfield’s Kenzie’s Point in July 1779, townspeople knew disaster was in store for coastal Connecticut. Some, however, saw British flags as a herald of freedom.

Days earlier, Sir Henry Clinton, Commander-in-Chief of British forces during the American Revolution, issued a stunning decree called the Philipsburg Proclamation. “I do promise to every NEGROE who shall desert the Rebel Standard, full security to follow within these Lines, any Occupation which he shall think proper.” Without delay, enslaved people answered the call. The proclamation kicked off a mass exodus of Black enslaved people from American-held territories, including the town of Fairfield.

The American Revolution and Escaping Slavery

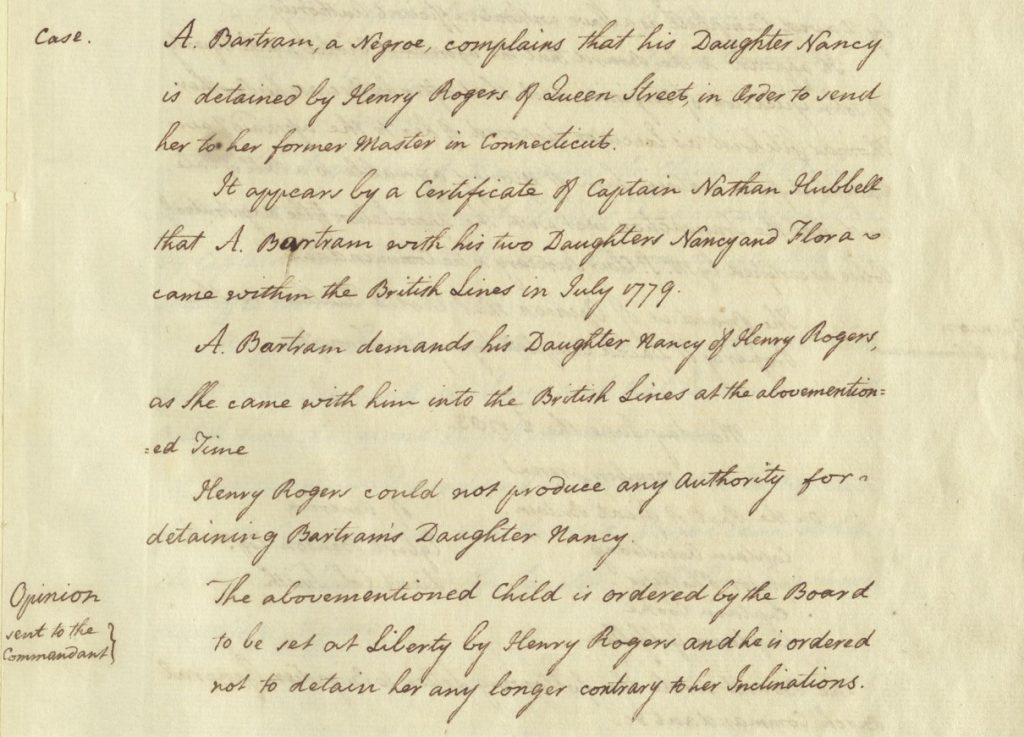

Advertisements by Peter Burr and Robert Rumsey of Fairfield in The Boston News-Letter, 1711 – Geneology Bank. Used through Public Domain.

Connecticut has a long history of enslaved people fleeing bondage and charting a course for themselves outside the bounds of slavery. As early as 1711, The Boston News-Letter, the country’s first published newspaper, advertised for the recapture of runaway enslaved people from Connecticut. Importantly, the first two such ads came from the town of Fairfield.

But it was the Revolutionary War and Enlightenment ideas which gave the cause of “freedom” the biggest boost. As Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence, “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” were “unalienable rights.” It was a message that rang true across the rift of Black and white, yet hundreds of thousands of people remained enslaved when the Continental Congress published the Declaration of Independence. While the white populace was concerned with taxation, irksome government regulations, and a lack of political power, Black Americans hoped that this new philosophy would allow them the freedom to control their own bodies, live in united family units, and reap the rewards of their own hard work.

Slavery Grows Unpopular in England

Despite the newly defined United States’ assertion of individual rights, support for slavery remained fairly intact. On the other side of the Atlantic, however, opposition to the practice of forced Black labor had begun to grow. In a 1772 decision, Chief Justice William Murray—England’s most powerful judge and 1st Earl of Mansfield—reportedly declared that “the state of slavery is of such a nature, that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political.” While scholars still debate the extent of the Somerset v. Stewart decision’s impact on the end of slavery in England, it exposed that common law did not support slavery. Murray, however, did not implicate the British colonies in his ruling on slavery. This split in attitudes among English and American presented a unique opportunity for the British military when war broke out.

Chief Justice Murray’s decision in 1772, Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation in 1775, and General Clinton’s Philipsburg Proclamation in 1779 presented enslaved people with an increasingly enticing offer: abandon the homesteads of Patriot enslavers, work with the British, and receive freedom for yourself and your family. It was a tactful play by the British military—they simultaneously grew their ranks while also depriving Americans of a crucial source of labor. Thousands of enslaved people in the American colonies accepted the offer.

The Burning of Fairfield Presents Opportunity to Escape

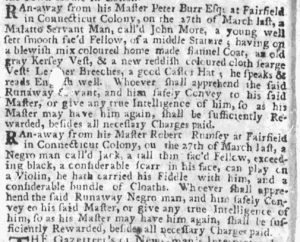

Burning of Fairfield, 1779 – Connecticut Museum of History and Culture. Used through Public Domain.

July 7, 1779, presented a perfect opportunity for enslaved people in the town of Fairfield, Connecticut. With more than two thousand British soldiers marching through the streets of an almost undefended Patriot town, several enslaved people were able to make their escape—including a man in his early 20s named Toney.

That evening, British troops set fire to a majority of downtown Fairfield, ransacking homes and exchanging gunfire with townspeople. In the chaos, Toney, with his two young daughters in tow, fled slavery on the estate of Job Bartram, a captain in the town’s militia. Though no one recorded the details of their escape, when British troops returned to their ships and sailed across the Long Island Sound to the Loyalist stronghold of Huntington, New York, Toney and his daughters, Flora and Nancy, were on board.

For the next several years, Toney lived in British-controlled New York, probably receiving a meager wage for the work he provided to the British troops. Whether he was cooking, chopping wood, or carting supplies, the arrangement was undoubtedly an improvement from his life in Fairfield.

A Future After Escape

The danger, however, was not over; in spring 1783, Toney made a bold demand. In a formal petition, he pressed the British military to protect his family. At some point during his stay in New York, Nancy, Toney’s young daughter, was kidnapped. In a city defined by anonymity and fast-paced enterprise, the abduction of Black people had become a profitable business. Both enslaved and free Black people were routinely abducted and sold to slave traders and ship captains. Most of these kidnappers headed south, where free Black people were rare and the market for bound labor seemed insatiable.

A Black Wood Cutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia, 1788 – by Captain William Booth, Nova Scotia Archives. Used through Public Domain.

Nancy, however, found herself in the hands of ship captain and merchant, Henry Rogers, who operated his shipping business out of a store on what is now Pearl Street. Though Rogers co-published a pledge of loyalty to King George III in the Supplement to the Royal Gazette, his commitment to earning money was more intense. According to British military records, Henry Rogers detained Nancy with the intention of selling her back to her former enslaver.

This planned kidnapping was not only a crime, but an affront to Roger’s proclaimed loyalty to Great Britain—he defied the orders of the British government by reenslaving an individual who had already been granted freedom. Having not found any record showing that Henry Rogers legally owned Nancy, the British military commanded that she be released and reunited with her father.

Whether the British military was able to secure Nancy’s release is not currently known—ledger books suggest not. When British troops evacuated New York City at the end of the Revolutionary War, they resettled many Loyalist refugees in British-held Canada. To keep track of Black Loyalists, the military put together a ledger book, titled The Book of Negroes. This book makes one thing painfully clear—when 25-year-old Toney (who had adopted the surname “Bartram”) boarded the Brig Concord en route to Canada in 1783, he traveled alone. Nine years later, a Tony Bartram was recorded as a sailmaker living in the remote coastal town of Guysborough, Nova Scotia.

Little else is available to expand upon the stories of Toney, Nancy, or Flora Bartram. But perhaps the bravery of Toney in his willingness to lead his family through a battlefield, live as a refugee, demand the safety of his daughter, and start his life over almost a thousand miles from home paid off. In 1871, the Canadian government conducted a census of its population. When census workers came to the town of Manchester, just a few minutes from Guysborough, they found a Black woman named Margaret “Bartrom” along with her five small children. Margaret’s farm stood square in the middle of a community of Black Loyalist descendants.

Alec Lurie is the Research Project Lead for the Fairfield Slavery Project, as well as a PhD student at Stony Brook University.