by Andy Piascik

The first two decades of the 20th century were a time of wide-scale dissent from the American dream. It was an era of bohemian salons, such as the one centered around the Greenwich Village apartment of Mabel Dodge. More explicitly political were radicals close to the Socialist Party and the Industrial Workers of the World who supported labor strikes in Lawrence, Massachusetts, and Paterson, New Jersey, and, for a short time, the Russian Revolution.

Some straddled both worlds. Their numbers included photographers such as Carl Van Vechten, the novelist Neith Boyce, poets such as Max Eastman, and the painters Charles Demuth and John French Sloan. More than a few served as hangers-on, usually men of comfortable means who spent far more hours chasing a good time than they did engaged in productive labor. Others, such as Big Bill Haywood, Margaret Sanger, and Emma Goldman, became outsized characters known and loved primarily as men and women of action, pushing at the outer edges of society.

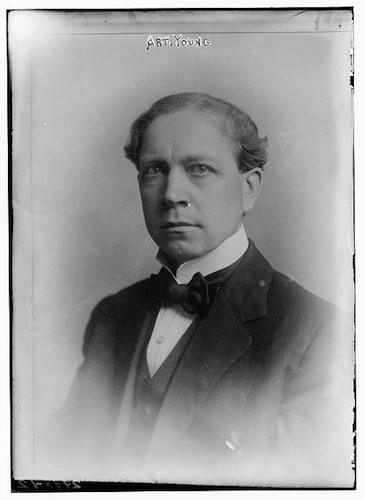

Cartoonist Art Young, ca. 1910-15, glass negative – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Perhaps the most prevalent dissenters of the era were the journalists—Lincoln Steffens, John Reed, Louise Bryant, and Walter Lippmann, among others. Included in this group was cartoonist Art Young who, even among a crowd known for individuality, was one of a kind.

The Conservative Roots of a Radical Cartoonist

Born in Illinois in 1866, Young grew up in Wisconsin. He proved different from Reed, Goldman, and the others in that he embraced conservatism for much of his life and worked in the mainstream for many years, including at the rabidly right-wing Chicago Tribune. It was not until Young passed the age of 40 that he embraced socialism, but once he did, it became central to his work as a cartoonist.

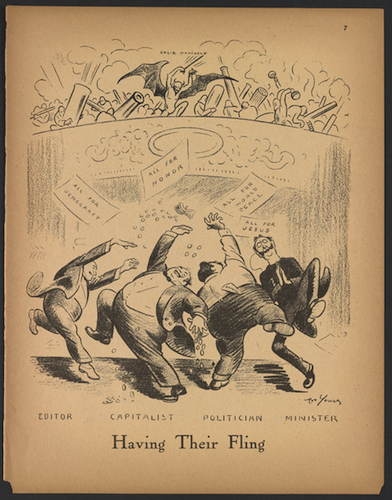

Young is known best for the cartoons he designed from 1911 to 1917 for The Masses, a left-wing monthly magazine of which he was co-editor. Among his best and most controversial cartoons were those critical of US involvement in the First World War. For one cartoon, entitled “Having Their Fling,” authorities arrested Young (along with Reed, Eastman, and others from The Masses) under the newly passed Espionage Act. The magazine staffers initially faced 20 years in prison but two trials ended in hung juries and authorities eventually dropped all the charges. The trials and ongoing government harassment, however, forced The Masses to cease publication.

Art Young, “Having Their Fling,” September 1917, The Masses – Researching Greenwich Village History

Art Young’s Farm in Bethel

Around 1900, Young purchased a house and four acres of farmland in Bethel, Connecticut. Initially the house was a country retreat, but shortly after the Espionage Act trials, Young began spending most of his time there. He continued to draw cartoons for a variety of publications, including The Liberator, a magazine founded in 1918 by his comrades as a successor to The Masses.

Both The Masses and The Liberator featured high-quality art, including covers of color cardstock that proved very striking in style, color, and content, and Young found his work featured numerous times. Later in his life he also drew for the New Yorker, the Saturday Evening Post, and Collier’s Weekly. In his seventies, Young experienced health and financial problems that resulted in his having to sell his Bethel property in 1940. He returned to New York and died there in 1943 at the age of 77.

Before he moved back to New York, Young put many of his original works (6,000 by one account) into storage. Some of those works are on display at the Art Young Gallery, an institution established in Bethel by residents determined to keep alive Young’s legacy and relation to the town. The gallery resides just a mile from the house where Young lived and in March of 2015 featured the first exhibit of the cartoonist’s work since 1939. The Bethel Historical Society also recently brought out Types of the Old Home Town, a previously unpublished manuscript by Young about his years in Bethel and the people he knew there.

Bridgeport native Andy Piascik is an award-winning author who has written form many publications and websites over the last four decades. He is also the author of two books.