By Gregg Mangan

During World War II, the United States government instituted a national farm labor program to help provide American farmers with the workers they needed to harvest their crops and keep their farms in operation. Under the jurisdiction of the US Department of Agriculture and the Extension Service, the Emergency Farm Labor Program often relied on convicts, POWs, and workers from other countries to supply farmers with much needed help. One of the most important sources of labor, however, was the Women’s Land Army (WLA). Between 1943 and 1945, the WLA trained and placed millions of American women on farms. The roots of this program date back to the First World War and were modeled after Great Britain’s Women’s Land Army and successful state-run programs like the one in Connecticut.

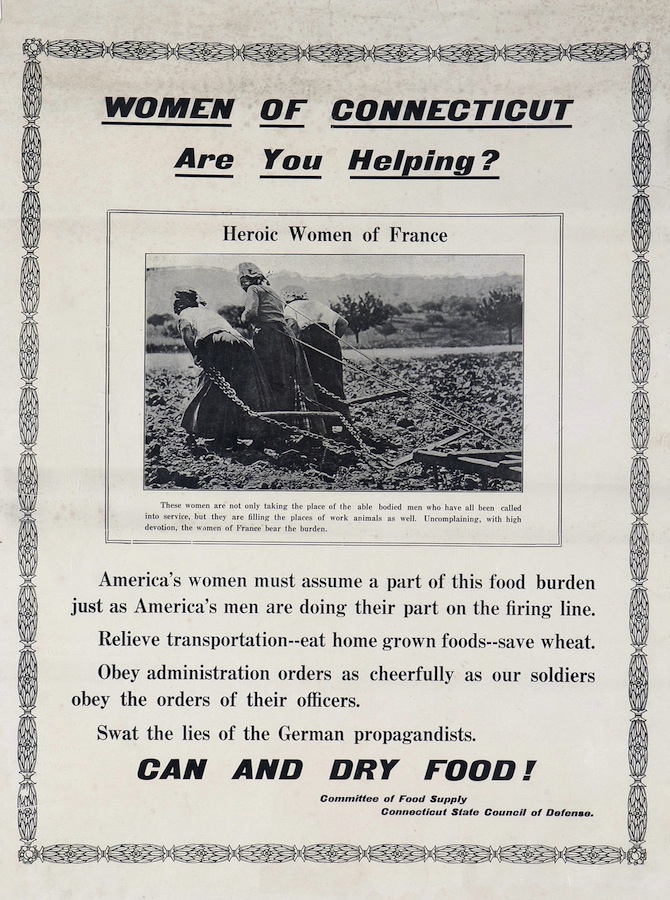

Poster from the Committee of Food Supply, Connecticut State Council of Defense, Women of Connecticut, are you helping?, ca. 1917 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

The Women’s Land Army and WWI

During the First World War, Americans believed that, in addition to weapons and raw industrial materials, food was an essential contributor to victory in Europe. In Connecticut, as in many other states, women became an increasingly important resource in food production. Local women from rural backgrounds proved more adept at agricultural tasks than any supply of labor, male or female, from urban areas. These so-called “farmerettes” made up the backbone of Connecticut farm labor throughout much of the war.

The WLA sought women between the ages of 18 and 40—making certain they passed a physical exam before assigning them to a farm. Enlistments ranged from 6 weeks to an entire growing season. Given housing on or near the farms on which they worked, the women supplied their own blankets, sheets, towels, and clothes. The program also stipulated that the women make their own beds and wash their own dishes. Much of the remaining housework fell to a “chaperone.”

Chaperones were the hardest positions to recruit for in the WLA. The organization sought “women of a mature age” who were “sensible practicable women who will cook for the girls, who will advise them and be their [confidant], who will mother them when they are tired and make a cheerful atmosphere in the home.” The WLA assigned one chaperone to every group of 10 women. Each of the 10 women paid 50¢ per week to the chaperone for housekeeping. In turn, the chaperones reported to state and national WLA headquarters on the condition and progress of the workers.

A typical day for a Connecticut WLA worker started at 5:30 am. While much of their 8-hour workday involved supporting the functions of the few remaining men on the farm, women also drove tractors, operated corn planters, and milked cows. For this, the women working in towns like Middletown, New Canaan, Redding, and Greenwich made $2.00 per day. Some of the girls who signed up for the duration of the war took short courses in dairying and canning at the Connecticut Agricultural College. These women received positions on dairy farms that provided them with higher pay.

The WLA Returns to Support the WWII War Effort

The need for help from the WLA died out with the end of the war but began anew with the coming of the Second World War. In 1942, Mrs. Joseph Alsop reorganized the WLA in Connecticut. After initially balking at the idea of hiring women to perform physical labor, farmers like Louis Tolles of Southington expressed genuine enthusiasm for the diligence and dedication shown by the WLA workers. Tolles claimed they accomplished more for him than his previous all-male staff ever did.

Connecticut Women’s Land Army, 1943 – Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries and Connecticut History Online

The achievements of WLA workers brought success stories in from all over the state. In the summer of 1942, after being given only 8-days notice to organize, 80 workers (with the assistance of some local high school boys) picked 50,000 quarts of strawberries in Bolton. The ladies then utilized a deserted ice cream parlor for a recreation and dining hall while they picked vegetables in Southington, and then they moved on to provide 1,544 hours of labor for apple growers in Litchfield.

The women worked 6 to 8 hours per day and received a pay of roughly $8.50 per week. After paying for their boarding, they ended up keeping only about $3.50 of that weekly wage. On rainy days, when the fields sat idle, the women watched movies or went into nearby towns for ice cream or to shop. Despite the sunburn, poison ivy, and bouts of homesickness, the women embraced the opportunity to contribute to the war effort while expanding their own horizons. In fact, the program proved so successful that by 1943 there was a waiting list of women anxious to join the WLA.

Gregg Mangan is an author and historian who holds a PhD in public history from Arizona State University.