By Patrick Mahoney

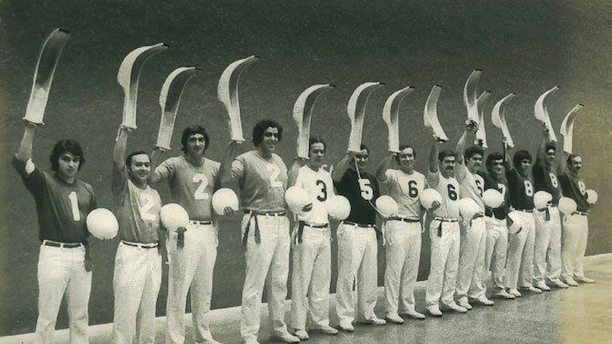

While jai alai is recognized as one of the fastest sports in existence, the game’s popularity in most of the United States dropped off considerably in recent decades. The game consists of players competing in an enclosed three-walled court (in what can be described as a variant of handball), during which ball speeds have been recorded upwards of 185 mph. The unique game originated as pelota vasca or “Basque pelota,” named after the Basque region of northern Spain. When the game became popular in Cuba at the turn of the 20th century, it became known as jai alai, which is Basque for “merry festival.”

Following its successful introduction into Cuba, jai alai quickly found a steady footing throughout Latin America and in the United States. The first jai alai fronton in the United States opened outside the grounds of the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. The sporting spectacle grasped the American public’s interest and new, permanent frontons soon emerged in Chicago and New Orleans. More than half a century later, in the era before legalized casino gambling came to Connecticut, jai alai centers sprang up in Milford, Hartford, and Bridgeport, and provided havens of excitement for sporting enthusiasts and gamblers from throughout New England.

Jai Alai Comes to Connecticut

After a 1973 proposal for a $7 million jai alai center in Hartford’s North Meadows, great excitement gripped the city’s residents. The year before, the legislature discussed the opportunity to procure extra income for the state by expanding gambling ventures such as the lottery, horse racing, off-track betting, and dog racing—all to be run by the Division of Special Revenue. While a number of the other moneymaking avenues failed to take off, by the summer of 1976, two large jai alai frontons opened in Hartford and Bridgeport, and quickly emerged as the premier legal gambling sites in the state. In 1977, a third jai alai fronton opened in Milford. Within a year, it had reached the level of success of its predecessors, accumulating over a million customers and over $70 million in wagers.

While the cash flowing into the sport helped create a market for it in Connecticut, it led to a certain level of disdain between the players and spectators, who did not always appreciate the intricacies of the contests taking place. One player, Jean Pierre Echeverry, a Basque native, reflected on such disconnects, noting to the Hartford Courant after a match in 1982, “Sure, it bothers me when they boo. If you win, you are a god, because you make them money. But some nights you play beautiful but you lose, and they boo you because they don’t understand.”

Gambling and Corruption

Cultural differences were not the only problem looming over the sport. Throughout its tenure in Connecticut, suspicions and assertions of corruption and match-fixing hung over the state’s jai alai industry. The culmination of such claims came with the 1977 conviction of numerous members of the “Miami Syndicate” gambling ring, who allegedly fixed up to 253 matches at the Milford location. The arrests were, at that stage, the most high profile of their kind in American jai alai, and sent shockwaves throughout the sporting community.

As individual states began to legalize casino gambling, the interest in jai alai gradually waned. Additionally, by 1992, Congress began cracking down on sports betting, asserting, “Sports gambling is a national problem. The harms it inflicts are felt beyond the borders of those States that sanction it.” Despite jai alai’s protection under the subsequent Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, the sport’s popularity in Connecticut quickly faded. The creation of Foxwoods Casino in 1986 and its further development in the early 1990s, coupled by the unveiling of Mohegan Sun in 1996, offered more diverse options to the crowds who once packed the stands of Connecticut’s jai alai frontons. In the spring of 1995, Bridgeport’s fronton closed its doors, and was replaced by a dog track. Five months later, the popular Hartford location closed. The Milford fronton outlasted its counterparts by 6 years, closing in December 2001.

Patrick J. Mahoney is a Research Fellow in History & Culture at Drew University and former Fulbright scholar at the National University of Ireland Galway