By Gregg Mangan

Salt is a mineral so readily available today that most Americans take it for granted. There is never a question of whether an adequate supply of salt exists or how to go about procuring it. Back in the late 1700s, however, Americans imported large quantities of salt from overseas. During times of war, this resulted in critical shortages of salt that Americans relied on both for seasoning and preserving their food. During these times, well-informed entrepreneurs took to generating domestic supplies to fill the market demand. One of these entrepreneurs was Amos Morris of East Haven.

Morris was a merchant engaged in trade with the West Indies. A direct descendant of mercantile entrepreneurs who left London for Massachusetts in the 1630s, he owned a wharf and large warehouse in East Haven that he utilized to grow his business.

Revolutionary War Creates Business Opportunity

When the Revolutionary War brought a temporary halt to salt shipments from the West Indies, Morris set up an operation to make his own. Setting out a series of wooden vats 30 feet long, 20 feet wide, and 10 inches deep, Morris collected seawater that he turned into salt through the process of evaporation.

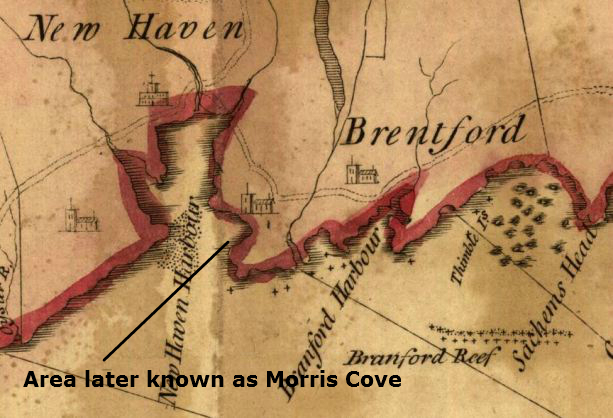

The Ancient Salt Works at Morris Cove from A Pictorial History of “Raynham” and Its Vicinity – By Charles Hervey Townshend, Published by New Haven, The Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor co. Used through Public Domain.

Each saltwater vat had a sliding cover used to protect the salt from rain and wind, as well as to keep dew from accumulating in it at night. After subjecting the water to the sun to promote natural evaporation, Morris utilized five boilers to rid the salt of its remaining water. He stored his product in sheds for a few days to allow the magnesium to drain off before re-dissolving and crystallizing his salt for market. Utilizing this process, Morris produced approximately a quarter of a pound of salt for every gallon of seawater he processed.

Unfortunately for Morris, in 1779, a series of raids along the Connecticut coast by British Major General William Tryon destroyed Morris’s salt manufacturing equipment. With the war ending shortly after, salt imports resumed and Morris never bothered to rebuild his facilities.

During the War of 1812, local residents briefly resumed producing their own salt but with little success. After moving their equipment away from local freshwater sources that compromised their product, a September 1821 storm destroyed the facility and salt production in East Haven ended.

Gregg Mangan is an author and historian who holds a PhD in public history from Arizona State University.