By Nancy Bonuomo for Connecticut Explored

2013 marked the 100th anniversary of Connecticut’s Workers’ Compensation Act. Originally called the Connecticut Workmen’s Compensation Act, the law represented a seismic shift in industrial policies and attitudes toward workers and those who suffered workplace injuries. Prior to its adoption, employees who attempted to sue an employer for injuries that occurred while at work were confronted with the “unholy trinity” of legal defense doctrines. The employer could claim that the injury resulted from the employee’s contributory negligence, that it was caused by the negligent actions of a fellow employee, or that the employee had assumed the risk of injury when he agreed to accept the employment situation. The odds favored the employers in defeating any action brought by an injured employee or the employee’s survivors.

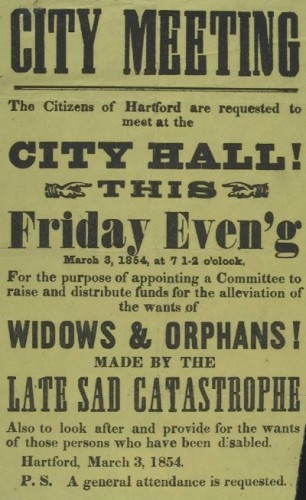

Broadside printed after the Fales & Gray steam-boiler explosion – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

Industrial Revolution Brings Host of Machine-Related Injuries

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, work became more mechanized and injuries increasingly resulted from human interaction with machines. Employers viewed work injuries as part of the cost of doing business, and that cost was relatively low. Developing and following safety measures that would reduce productivity was not viewed as cost effective.

With mechanization of the workplace, however, injuries tended toward the catastrophic, e.g., the loss of hands, limbs, and life. Eventually, the idea of a government-based program assuring compensation for industrial accident victims became one of the ideas advanced by mid-19th-century socialist reformers.

The concept first took hold in Europe, where the Industrial Revolution had advanced more quickly than in the United States. In 1884 Chancellor Otto von Bismarck of Germany enacted such a workmen’s compensation scheme. England adopted a similar system in 1897.

Programs in the 20th Century

As the 20th century turned, advocates for a workmen’s compensation program began to rally in the United States. While some states and the federal government attempted to enact various employment injury compensation programs, they were largely nullified as unconstitutional when subjected to judicial review. Before the states or the federal government could effectively enact any such legislation there needed to be a philosophical retreat from the laissez faire economic theory embraced by industrialists and a majority of the justices on the United States Supreme Court. One of the hallmark examples of the Court’s laissez faire-guided opinions was its decision in Lochner v. New York (1905), which held that the government could not limit the hours worked by an individual as it was part of the worker’s liberty interests to contract to work as many hours in a day as he desired. Lochner embraced the concept of a free market and rejected the government’s attempt at regulation.

However, even the United States Supreme Court eventually came to accept the appropriateness of some government regulation. President Theodore Roosevelt’s attempts at commercial and industrial reform are legendary, but his initial attempt at enacting an industrial accident program for railroad workers, the Federal Employers Liability Act of 1906, was found unconstitutional. Ultimately, Congress passed the Federal Employers Liability Act of 1908, which withstood judicial review.

Tragedy at Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Increases Support for Reform

In the wake of the great Shirtwaist strike that took place between November and February 1910 among New York City garment workers, the New York legislature enacted a “compulsory” industrial accident compensation act. On March 24, 1911, the New York Court of Appeals (the highest-level state court in New York) in Ives v. South Buffalo Railway Company (1911) held that the New York Act was unconstitutional. The very next day, March 25, 1911, on a late Saturday afternoon, 146 garment workers died in a fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City.

After the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire came a spate of individual state legislatures’ passing some form of Workers’ Compensation. Wisconsin led the way in 1911. While Connecticut did not enact its Workers’ Compensation Act until 1913, the topic was discussed among policy makers. The sticking point in early debates was the compulsory nature of the proposed legislation. In 1913 a compromise was made in the form of an act that would only pertain to those employers with 5 or more employees.

Although Connecticut may not have been the among the first of the states to adopt a Workers’ Compensation Act, it is with pride that we can state that Connecticut’s act has proven to be not only a reflection of noble humanitarian objectives but sound economic policy as well.

Connecticut has managed to preserve the integrity of its act throughout the years while allowing it to adapt to the dynamic and ever-changing nature of work. Much of the remedy designed and codified 100 years ago exists as vibrantly today as it did then.

Nancy Bonuomo is the chief law clerk for the Connecticut Workers’ Compensation Commission.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 12/ No. 1, WINTER 2013/14.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.