By Christine Woodside

The American shad is a fish native to Connecticut. It has provided food, income, and culture to native tribes and settlers for hundreds of years. Shad migrate by the hundreds of thousands from the Atlantic Ocean up the Connecticut River each spring. Shad once ran in several rivers, including the Thames, Housatonic, and Naugatuck , but industry, dams, and a lack of streams in which to spawn stopped them. Today they are found in the Connecticut, Pawcatuck, Farmington, and Shetucket rivers. So significant is the American shad’s contribution to local history that, in 2003, the Connecticut General Assembly designated it the state fish.

A member of the herring family, the American shad—Alosa sapidissima—is anadromous: it migrates from its saltwater habitat upriver with the single purpose of reaching a specific freshwater stream in which to spawn. It usually makes the journey from mid-April to mid-June, swimming upriver in groups without stopping to eat. The fish migrate in waves, or runs, that experts say are hard to predict. For shad lovers, the art of catching the wave of shad has created a culture around shad fishing and eating timed with the height of the harvest in May and early June.

American shad – alosa sapidissima

Early Harvesting

Historians know shad were a major source of food for American Indians. Evidence of their stone weirs, or low dams, can be found in Old Saybrook’s South Cove. Fish swam into the shallow cove as the tide came in, and as it receded, they became trapped by the strategic stone walls.

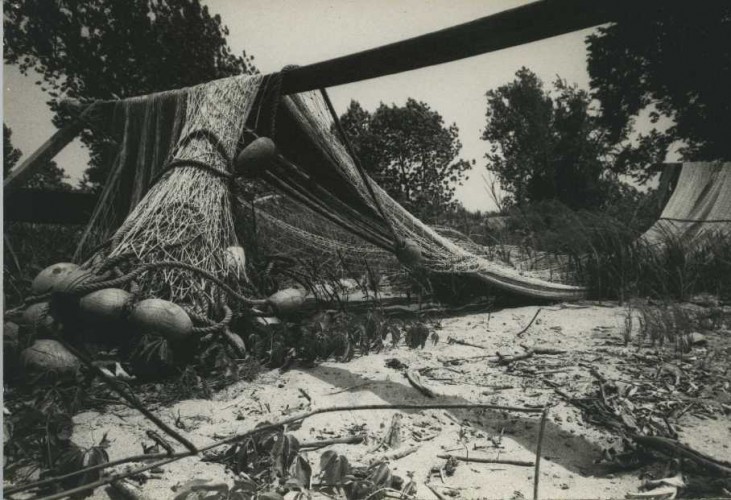

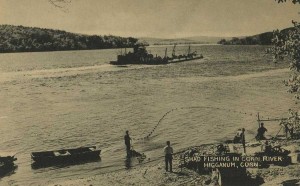

After the colonial period, and until the 1950s, fishermen harvested shad of 3 to 6 pounds each by the hundreds by pulling vertically hung nets through the water—a method called haul-seining.

In the early 1800s, fishing companies ran large operations during shad runs, and local farmers came off their land to work around the clock on the piers. As the riverfront developed in the mid-1800s, the shad suffered and harvests dramatically declined, due, in part, to the construction of the Holyoke Dam in Massachusetts.

By the 1860s, shad fishing yielded low returns and the organized fishing companies ceased operating. A program of lab breeding and egg-planting below dams boosted numbers for a time, but by the late 1800s, shad harvesting had become a small-scale pursuit.

Fishways Promote Unsteady Recovery

In the late 19th century, engineers attempted to solve the problems caused by dams and built fish ladders. These allow fish to jump inclining steps with resting pools at measured intervals. The ladders had little success and by 1922 the entire shad catch for the season was reported to be only about 14,000. By 1955, the Holyoke Water Power Company built a fish lift (a mechanized fish “elevator”) at the Holyoke Dam. This allowed shad to pass the dam in significant numbers and spawn upstream. By 1967, 19,000 shad rode the elevator to circumvent the Holyoke Dam. By 1970, that number had risen to 66,000. Other fish ladders to the north helped to further normalize migration.

Despite the recovery brought about by fishways (the name for devices such as fish ladders and lifts), the numbers of shad in the Connecticut River appear to fluctuate greatly from year to year. Since 1978, the State of Connecticut has monitored shad populations. For instance, in 1983, the state estimated a river shad population of 1.5 million. About 530,000 were counted at the Holyoke Dam, where staffers and video cameras provide a fairly accurate count of adult shad returning to spawn. In 2004, the river shad estimate was only about 351,000 (192,000 passed Holyoke). Since then, changes to the Holyoke lift have made it more difficult to estimate river-wide populations, but the count at the dam continues to decrease.

Preserving Tradition

20th-century photograph of shad fishing on the Connecticut River, Haddam – Haddam Historical Society

Shad numbers are high enough, year to year, to allow for a dizzy spring season of shad-related community events, such as the annual Shad Derby in Windsor, Connecticut, and “planked shad” dinners, at which cooks nail shad to large buttered boards suspended near coals. This technique is believed to have originated with native tribes. Shad is considered an acquired taste; it’s comparable to the strong-flavored and slightly oily bluefish. And, filleting shad is no easy feat. Each shad has as many as 1,000 bones, and removing the bones is considered an art form in the lower Connecticut Valley. In earlier times, at the shad shacks where commercial fishermen sold their catches, those boning the shad would put a towel over the fish to hide their special techniques.

The ability to buy fresh fish from around the world year-round has blurred the importance of a fish such as shad to the local economy and to local and regional foodways and culture. Gone are the days when men earned their income from shad fishing and teenagers could procure someone’s small wooden boat, drag a net, and sell a few shad to make extra money in the spring.

Christine Woodside of Deep River, Connecticut, edits Appalachia journal and Connecticut Woodlands magazine and writes about the environment, climate change, and American history for periodicals.