By Michael C. Dooling for Connecticut Explored

…this sequestered glen has long been known by the name of SLEEPY HOLLOW…A drowsy, dreamy influence seems to hang over the land, and to pervade the very atmosphere.…the place still continues under the sway of some witching power, that holds a spell over the minds of the good people, causing them to walk in a continual reverie.

—Washington Irving, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent, 1819/20

Sometime after Washington Irving wrote his story about Ichabod Crane and the terror that beset him, Milford earned a nickname that has been long since forgotten: Sleepy Hollow. Exactly when or why this name became associated with Milford is something of a mystery, but there are some interesting connections between the town and the tale. In 1838 Milford resident Edward Lambert wrote in his History of the Colony of New Haven, “The inhabitants of Milford are mostly farmers, and retain in an eminent degree the manners of the primitive settlers. It being difficult to change long established habits, they are not celebrated for keeping pace with the improvements of the age.”

Milford’s sleepy reputation became entrenched and was proudly displayed on a banner at a political rally in 1840. Five thousand men descended on Hartford to attend a meeting of the Whig Young Men of Connecticut. Among them were 1,000 arriving by train from New Haven. As they paraded from the railroad station, accompanied by a marching band, a Milford contingent sported a banner in support of the new presidential nominee:

OLD MILFORD, THEY CALL HER “SLEEPY HOLLOW,” She’s wide awake for HARRISON AND REFORM

That political banner wasn’t the only one to refer, albeit indirectly, to Irving’s home territory. William Henry Harrison’s opponent was incumbent President Martin Van Buren of Kinderhook, New York. Irving had written “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” while staying as a guest at Lindenwald, Van Buren’s estate. The North Haven banner read, “Know, Man of Kinderhook, the People will meet you at the Polls.”

Harrison and his vice-presidential running mate John Tyler won the election that year. It was the first national victory for the Whig party, thanks in part to Milford voters who apparently woke up and supported “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too!”

The endearing sleepy image was reinforced when an article describing Milford appeared in New England Magazine in 1889. “I suppose a drowsier, lazier town of its size does not exist in all the land of steady habits,” wrote its author. “The leisurely Spanish custom of taking siestas in the middle of the day is followed by the people to an extent which is exceptional, and which would shock the overworked citizens of the great American cities…. The reader must not understand siesta to be synonymous with nap…. The Milford siesta…is simply a time set apart systematically for rest and seclusion during the heat of the day.”

Irving’s Ichabod Crane Hailed from Connecticut and His Real-life Inspiration Might Have, Too

Milford’s sleepy reputation and Washington Irving’s “Sleepy Hollow” share some intriguing links. The well-known tale tells the story of Ichabod Crane, a schoolmaster living in the Hudson Valley, and his encounter with the Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow. In his story, Irving wrote that Crane had moved to Sleepy Hollow from Connecticut:

In this by-place of nature, there abode, in a remote period of American history, that is to say, some thirty years since, a worthy wight of the name of Ichabod Crane; who sojourned, or, as he expressed it, “tarried,” in Sleepy Hollow, for the purpose of instructing the children of the vicinity. He was a native of Connecticut, a State which supplies the Union with pioneers for the mind as well as for the forest, and sends forth yearly its legions of frontier woodsmen and country schoolmasters.

Washington Irving apparently patterned the “worthy wight” Ichabod Crane after his close friend Jesse Merwin, a schoolmaster who lived in the town of Kinderhook, New York.

Just who was this Jesse Merwin? The historical record renders confusing, conflicting information. One genealogy indicates a Jesse Merwin was born in Durham, Connecticut, while another lists him as having been born in Milford; both list the same birth date of August 25, 1784. Yet the Vital Records for neither Durham nor Milford list a Jesse Merwin born in that year; the Milford records list a Jesse Merwin as being born December 23, 1782. An 1898 article in the New York Times offers another view. The author, Harold Van Santvoord of Kinderhook, New York, was writing about whether “Sleepy Hollow” was really in Tarrytown or Kinderhook, New York. He lived in Kinderhook and knew one of Jesse Merwin’s sons, who shared with him his version the family’s history. He wrote (referring to Merwin as “Ichabod Crane”):

I have taken great pains to look up the Merwin genealogy, and through the courtesy of a son of Ichabod Crane, still living here and highly esteemed for his uprightness of character, have had access to a printed record tracing back the family of English and Welsh extraction on American soil to 1645, when the original immigrant became owner of a large tract of land lying mostly in the town of Milford, Conn…Descendants of Ichabod asseverate that after migrating from Milford, Conn., he lived continuously in Kinderhook…

The exact date Merwin moved to Kinderhook is uncertain, but in 1808 schoolmaster Jesse Merwin is found living there, married to Jane Van Dyck, with whom he eventually had 10 (or 11) children.

At least two letters appear to document the Irving-Merwin relationship. An 1851 missive from Irving to Merwin is a folksy reminiscence about their lives in Kinderhook:

Your letter was indeed most welcome—calling up as it did the recollections of pleasant days passed together in times long since…You told me the old school-house is torn down and a new one built in its place. I am sorry for it. I should have liked to see the old school-house once more, where after my morning’s literary task was over, I used to come and wait for you occasionally, until school was dismissed….

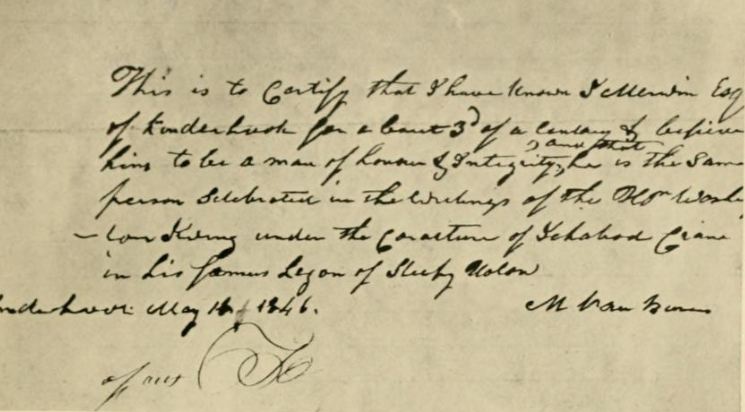

A second letter notes that Merwin was the inspiration for Ichabod Crane. Former President Martin Van Buren wrote a letter of introduction for Merwin in 1846 when he journeyed to New York City for his Methodist church:

This is to certify that I have known J. Merwin, Esq. of Kinderhook for about 3d of a century, & believe him to be a man of honour & integrity; and that he is the same person celebrated in the writings of the Hon. Washington Irving under the character of Ichabod Crane in his famous Legend of Sleepy Holow [sic] —M. Van Buren

Letter from Martin van Buren verifying that Jesse Merwin was the inspiration for Ichabod Crane from A History of Old Kinderhook by Edward Collier

Whether Milford’s old moniker “Sleepy Hollow” can be directly traced to the Irving-Merwin friendship or was simply a nickname bestowed on a quiet, rural community based on the popularity of the story may never be known with certainty. However, it is likely that the Milford Merwins kept track of their relative in Kinderhook and his friendship with Irving. The Merwin family, or perhaps Washington Irving himself, may have bestowed the name Sleepy Hollow on Milford because the “real” Ichabod Crane was born and raised there. What is known for certain is that the lazy, sleepy reputation of a town unwilling to change has been lost, for many good reasons, with the passage of time.

Michael C. Dooling, news librarian for the Republican-American in Waterbury, is the author of two books on Milford, An Historical Account of Charles Island (2006) and Milford Lost & Found (2009), and one true crime work, Clueless in New England(2010).

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 10/ No. 4, FALL 2012.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.