By Dawn Byron Hutchins

Joseph Toy, his wife, and their three children arrived in New York City from England on a mid-August day in 1839 on a mission for his employer, the English fuse manufacturer Bickford Smith & Davey. Three years earlier the company, whose founder invented the safety fuse, had entered into a partnership with Connecticut native Richard Bacon to manufacture safety fuses at his East Weatogue farm. Toy, a bookkeeper and Methodist lay preacher, was given the task of representing Bickford Smith & Davey’s interests and steering their American outpost, Bacon, Bickford, Eales & Co., onto a profitable course. In the process, Toy created a Connecticut family business that 176 years later has grown into an international conglomerate.

Joseph Toy – Simsbury Historical Society

The Power of Gunpowder

In the early 1800s, Cornish miners used black powder, made from saltpeter, sulfur, and charcoal, for hard-rock mining of tin, copper, and other ores. The powder, laid in lines or encased in connected goose quills, was ignited and burned toward the explosives, eventually setting them off. The practice was unpredictable and dangerous: either they exploded too early or too late, both instances jeopardizing the miners’ lives.

In 1831, William Bickford was granted Royal Patent No. 6159 for “Safety Fuze for Igniting Gunpowder used in Blasting Rocks, Etc.” Bickford introduced black powder into the process of manufacturing rope and yarn: lengths of spun, twisted, and countered flax, hemp, or cotton yarn were filled with powder and then varnished to become waterproof. The fuse burned at a steady, predictable rate and allowed for controlled remote ignition.

England Partners with US in the 19th Century

England in the 1830s was in the throes of its industrial revolution. It was also protective of its burgeoning industrial technology, choosing not to share it with its former colonists. What it did share was through partnerships, with the British having the upper hand in management. Bacon, according to his contemporary and local historian Lucius I. Barber in A Record and Documentary History of Simsbury, established Bacon, Bickford, Eales & Co. in the East Weatogue section of Simsbury in 1836. “This, and a similar one in England, of which this is understood to be a branch, have a monopoly of the business, and furnish safety-fuse for the world, and have the world for a market.”

Before this venture, Richard Bacon (1775-1867) was involved with the Phoenix Mining Company formed in 1830 to mine a rich vein of copper that ran through the East Granby hills. Early colonial mining on the site had left hand-hewn caverns and tunnels that were used as Newgate Prison until 1823 when Connecticut established a state prison in Wethersfield and the defunct copper mine was sold. It is likely that Bacon agreed to become a sales agent for the English fuse makers as a way to obtain the fuse technology for his own needs. “The first shipment of fuse was subjected to a twenty-five percent ad valorem duty, which, added to the cost of shipping and handling, plus Bacon’s commission, raised its cost to the American consumer to well over fifty per cent above its English price,” wrote Joseph Toy and former chairman of the board John E. Ellsworth in 100 Years:The Ensign-Bickford Company and the Safety Fuse Industry in America: a Record of One Hundred Years of Achievement 1836-1936. Producing the fuse on American soil made economic sense.

Toy and his family settled in East Weatogue close to Bacon’s fuse works. He immediately set to work using his skills as a bookkeeper to organize the almost non-existent financial records of the firm. As a Methodist lay minister he set a moral tone in the firm and his new community. He insisted that records be kept, that they accurately reflect the state of the partnership, and meet the needs of the English firm, conditions that had been lax under Bacon’s leadership. According to Ellsworth, “The general unsatisfactory situation … convinced the English partners that someone should be sent to America to more fully represent their interests, particularly to keep the books of the new company and to send over promptly and regularly a summary of the accounts.” Toy became the eyes and the ears for the main office in England and assumed more responsibility in the American partnership. Bacon and Toy endured an uneasy relationship punctuated by mistrust and misunderstanding.

Powder wagon and horse (powder was stored in the powder woods and delivered daily to the factory for production) – Simsbury Historical Society

Accidents Befall the Safety Fuse Company

The production of the safety fuse was fraught with accidents, as the black powder and varnishes used were volatile. The Simsbury “factory” was located near the intersection of today’s Route 185 and East Weatogue Street on Bacon’s farm. The wooden buildings were cobbled together from the farm’s outbuildings. Many Connecticut industries began in barns or as adjuncts to the family farm. Intermittent water from a small stream running downhill from Talcott Mountain to the Farmington River provided some power in addition to hand turning of the primitive rope-twisting machinery. A fire in the varnishing shed destroyed the fledgling operation on November 12, 1839. It was quickly rebuilt with new wood structures.

The Company Parts Ways

On March 15, 1851, the rebuilt factory burned down after friction from a piece of machinery ignited cotton lint. Toy, with the English partners’ blessing, took the opportunity to move the factory to its present site on the west side of the Farmington River—and to dissolve the partnership with Bacon. He renamed the company Toy, Bickford & Co. “The spirit of aggressiveness did not sit well with Richard Bacon. To him, Joseph Toy, was an upstart, a foreigner in spite of his American citizenship, and altogether too grasping,” wrote Ellsworth. New England was undergoing a financial and social upheaval as the Industrial Revolution took hold. An English immigrant who embraced the latest technology may have seemed too aggressive to a native-born son. Bacon and his sons, who held patents on improved safety-fuse manufacturing processes, had the dissolution thrust upon them, and they fought back by continuing to make safety fuses on their farm in East Weatogue.

The move to the Hopmeadow district of Simsbury gave Toy uninterrupted waterpower from the Hop Brook. It also put the factory alongside the Canal Railroad established on the old right of way for the Farmington Canal. Within three months of building a new factory, Toy was producing fuse. Competition soon appeared in the form of Bacon’s two sons, however, who, with some former employees, started the Climax Fuse Company in Avon, the next town over. In a letter from Toy to the English partners reproduced in Ellsworth’s 100 Years, “The people here seems [sic] to be fuse-making-mad. The price is falling constantly but like water it will find its level after awhile.” By 1859 Toy had either bought out his competitors or hired them.

Assembly Workers Faced Horrific Accidents

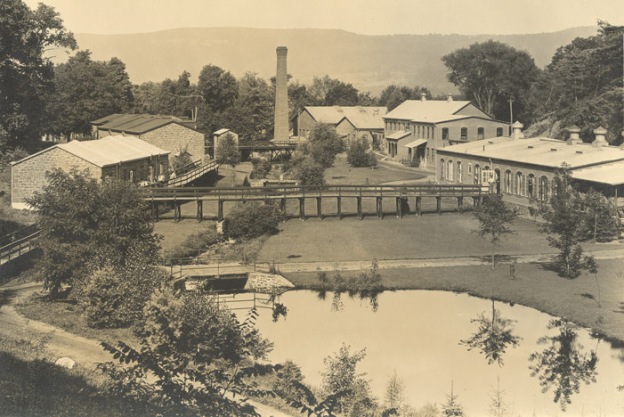

Ensign-Bickford fuse factory, Simsbury – Simsbury Historical Society

Girls as young as 14 worked on the fuse assembly lines and nimbly counter-wrapped powder-filled strands. The process left black powder on the workers, machinery, floors, and walls. In spite of stringent, for the time, safety measures, the work was risky. Still, there had been no loss of life in the various fires or explosions at the fuse factory—until December 20, 1859. “The Terrible Calamity At Simsbury” was the headline in the Hartford Daily Courant on December 21. The article described the explosion and fire that burned eight girls and young women to death and injured several other workers, including Toy’s own son Joseph. “The appearance of the place,” the article reported, “indicated that the woodwork of the building was saturated with powder…It appeared as if the fire had been driven down from the upper room with great violence upon the employees below.”

The horrific deaths of these young workers, who ranged in age from 14 to 33, were a huge blow to the community. Toy personally provided eight matching black walnut coffins with silver decoration and nameplates. A special sleigh was built to carry the dead to the cemetery in the center of town. The funeral cortege was said to be half a mile long; it was “followed by thirty two young men as pallbearers,” according to reports in the Hartford Daily Courant. A common plot next to that of the Toy family, marked by a brownstone shaft, stands in Simsbury’s Center Cemetery as a monument to workplace dangers in early industrial America. Toy took the lessons learned from the catastrophe and rebuilt his factory, this time with stand-alone stone and brick buildings.

The Company Faces Changes

The events of June 21, 1862, changed the course of Toy, Bickford & Co. Joseph R. Toy was his father’s heir apparent. In 1860, with his father’s financial help he was elected to the Connecticut legislature. He served on a committee to raise troops when the Civil War began in 1861. The younger Toy obtained a captain’s commission in Company H of the 12th Regiment Connecticut Infantry. On February 24, 1862, he sailed to Ship Island, Louisiana. His regiment went on to land at the occupation of New Orleans in May 1862. His death from disease at Camp Parapet near Carrollton, Louisiana, four months after he left Connecticut, altered his father’s plans for the family business.

It would now be the Toy daughters’ spouses who would take Toy, Bickford & Co. into the future. The first to marry was Susan Toy, in 1863, and her choice of Simsbury-born and Methodist-raised Ralph Hart Ensign provided her father and the firm with a successor. The Ensigns were Connecticut manufacturers and peddlers of tin goods and stoves. According to the 1860 Federal Census, Ralph was living with his brothers in Georgia, where they worked in a family mercantile business. During the Civil War, Ralph returned home to his family and supported the Union while his brother Nathan stayed behind to serve in the Confederate army. Nathan Ensign returned to Connecticut only after his death in 1889, when his body was interred in his family’s plot.

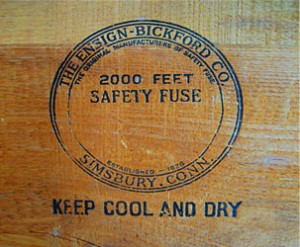

Ensign-Bickford Safety Fuse box – Simsbury Historical Society

The Toy Family Expands with the Business

Ralph Ensign had considerable business experience by the time he married and almost immediately made himself invaluable to his father-in-law. He was made a partner in 1870, and after his father-in-law’s death in 1887 his name replaced Toy’s on the company masthead.

Anne Toy married Lemuel Stoughton Ellsworth in 1866. He was brought into the family business with little experience. In 1867, sensing an opportunity, Joseph Toy sent him to California to build a satellite manufacturing facility. Despite Ellsworth’s lack of knowledge, he managed to build a factory in Alameda, California, that produced safety fuses for western miners. Ellsworth left California and the firm in 1871, returning to Hartford to join his brother’s seed and fertilizer business. In his place Toy sent his stepson James Bestor Merritt Jr. In 1876 Sarah Jennette Toy married Charles Edson Curtiss. Ensign, Ellsworth, and Curtiss would come together to provide leadership for Ensign-Bickford Company after Joseph Toy’s death in 1887.

A Merger and Two World Wars Drive Growth

In 1907 Ensign, Bickford & Co. merged with Climax Company to become The Ensign-Bickford Company. The ownership was now completely American. Simsbury assumed the aspects of a company town, including worker housing. Ensign-Bickford provided fire and safety services. Polish and Italian immigrants now worked the fuse lines, and workers would soon unionize. Ensign-Bickford management also served in elected and appointed town positions.

The advent of World War I saw demand for fuse products increase drastically. In 1917, upon the deaths of Ralph Hart Ensign and Lemuel Stoughton Ellsworth, their sons Joseph R. Ensign and Henry E. Ellsworth assumed leadership of the company. Cousins and extended family continued to join the firm. World War II and its military needs led to the invention of Primacord®—a hybrid detonating fuse made in various strengths. The late Donald Horton Shaw, a Purple Heart recipient whose father also worked for the company, recalled being issued Primacord® in the European war theater that he had been responsible for making in Simsbury.

Ensign-Bickford’s 20th-Century Contributions

Ellsworth Grant, in Exploding into The Space Age: The Story of Ensign-Bickford Industries, Inc., marks 1945 as the beginning of the company’s efforts to diversify. It made its first foray into manufacturing a non-fuse product during the 1930s with its Bankers Bag and Tracealarm enterprise. The bags, used to carry large amounts of cash for payroll, released smoke from a canister when they were interfered with, such as during a robbery. The success of this product line paved the way for creation of the company’s Bank Messenger Division. In 1947 the company acquired Cuprinol, Inc., maker of chemical wood and fabric preservation products. Ensign-Bickford went on to manufacture upholstery and other decorative fabrics under Ensford Yarn. These early ventures still had a tenuous link to fuse manufacturing through the raw materials they used.

Ensign-Bickford Company shipping department workers, ca. 1920 – Simsbury Historical Society

But the company’s current subsidiaries constitute a broader portfolio. Simsbury-based Ensign-Bickford Realty, for instance, develops and sells real estate. Ensign-Bickford Aerospace and Defense, also headquartered in Simsbury, creates devices used in missile, aircraft, and space vehicles, demolition work, and tactical payloads. EnviroLogix in Portland, Maine, generates testing kits and strips for use in food-production industries. Biomass Energy of Virginia makes wood-pellet fuel. DanChemTechnologies of Virginia manufactures feed additives, cosmetic denture materials, and specialty polymers. The cuddliest of the company’s diversifications is Applied Food Biotechnology of Missouri, which produces “palatability enhancers” for cat and dog food, making for tastier pet meals.

The safety fuse, the invention that helped build America’s railroads, mine her natural resources, and expand the Panama Canal and that also allowed farmers to blow up stumps in their fields, is no longer made in Connecticut. A greenway on the bed of the former rail tracks along Route 10 allows walkers and cyclists to pass within feet of the old fuse-manufacturing plant with its watercourse, quaint buildings, and explosive memories. Down the street, in a cemetery right out of Our Town, lie the remains of the man who in 1836 came to the Land of Steady Habits and made those habits his own. The family business he founded is still privately held, and his descendants continue to participate in its management.

Dawn Byron Hutchins is an independent historian and museum consultant and former executive director of the Simsbury Historical Society.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 10/ No. 4, Fall 2012.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.