The origins of Danbury’s hat-making industry date back to the late 18th century. It was then that Zadoc Benedict, having stumbled upon a way to make felt by adding heat, moisture, and pressure to animal pelts, began using his bedpost to mold felt into hats. He then hired a journeyman and two hat-making apprentices and started producing three hats per day.

Danbury proved an ideal location for hat making thanks to its abundant populations of beavers and rabbits for pelts and thickly wooded forests for firewood. It was not long before others, such as Russell White and Oliver Burr, joined Benedict in the industry. By 1809, there were 56 hat shops in Danbury—each employed approximately three to five men.

E. Sturdevant wool hat factory, Beaver Brook (Danbury), CT, drawing ca. 1858 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

In the early 1800s, Danbury produced mostly unfinished hats. Hatters softened and dyed the felt through an 18- to 20-hour boiling process, and molded the pieces into their proper shape. They then rolled the hats up by twos into paper and placed them in a linen bag, and from there, into a leather sack for shipment to New York by coach. Once in New York, craftsmen trimmed and finished the hats.

Fashion Shapes the Industry

Changing fashion trends placed continually evolving demands on hat makers to reinvent and refine their processes. In the 1830s, silk hats came into greater demand, followed shortly after by wool hats. To meet this demand, Danbury soon employed more hatters than all its other occupations combined. Consequently, by the 1850s, Danbury earned the nickname of “Hat City of the World.”

In addition to the fur and firewood the Danbury area offered hat makers, an ample supply of water proved critical for boiling pelts and powering machinery. In order to ensure a steady supply of water to the factories, authorities constructed a dam along the lower Kohanza Reservoir in 1860 and another along the upper reservoir five years later. This led to the worst flood in Danbury’s history when the icy reservoir broke through the dams in 1869 and poured millions of gallons of water through residential and commercial areas, killing 11 people.

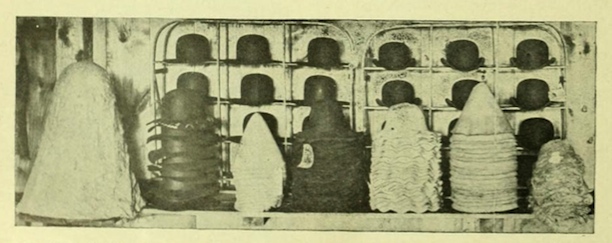

Hats in the various stages of manufacture from the “raw material” to the finished product from Connecticut Magazine’s article “Danbury Leads the World in Hatting” by J. Moss Ives, 1901.

After the industry recovered from the flood and the loss of business in the South during the Civil War, it brought prosperity to Danbury once again. In 1880 alone Danbury produced some 4.5 million hats. The hatters of Danbury prospered through constant innovation in their boiling, dyeing, cutting, and sizing processes, as well as by staying on top of trends in the hat market that witnessed the emergence of straw hats and hard derbies.

These changing trends unfortunately also helped bring about the industry’s demise. As covered transportation in cars and trolleys became more common, wearing hats began falling out of fashion. Additionally, the industry began to suffer from labor strife. Hatters unionized in 1880 and a series of strikes and lockouts soon followed.

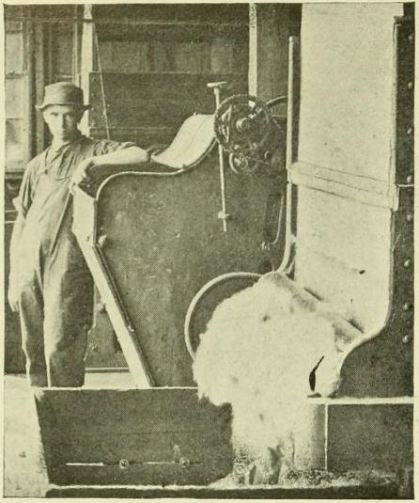

The process of “blowing” or separating the fur from the coarse hair from Connecticut Magazine’s article “Danbury Leads the World in Hatting” by J. Moss Ives, 1901

One of the most contentious issues among hatters unions was the deteriorating health of many of its members. The “hatter’s shakes”—tremors caused by damage to the nervous system from prolonged exposure to mercury—became as synonymous with Danbury as its headwear. The exposure to mercury came, in part, form the solution hatters washed animal pelts in which contained significant quantities of mercury nitrate. (It was not until 1941 that Connecticut governor Robert Hurley banned the use of mercury for this purpose.)

As labor relations worsened and the demand for hats declined, so, too, did the Danbury industry decline. In 1923, only six hat manufacturers remained, and by the 1950s, the Danbury Rough Hat Company stood as the last surviving hat enterprise in the city. Despite the end of large-scale hat making in Danbury, however, the city remains dedicated to preserving the memory of the time when Danbury was the center of the hat-making world. References to the once thriving industry abound in Danbury and continue to shape much of the city’s identity today.