…that by 1853, the era of steamboat transportation had largely given way to trains, but there was still a need to manage drawbridges for safe passage of both modes of transportation.

At 8:00 am on May 6, 1853, Dr. Gurdon Wadsworth Russell of Hartford and other physicians boarded a train in Manhattan along with 150 other passengers to return home from the annual meeting of the American Medical Association. At 10:15 am, Captain Byxbie of the Pacific steamboat whistled for passage through the drawbridge at South Norwalk.

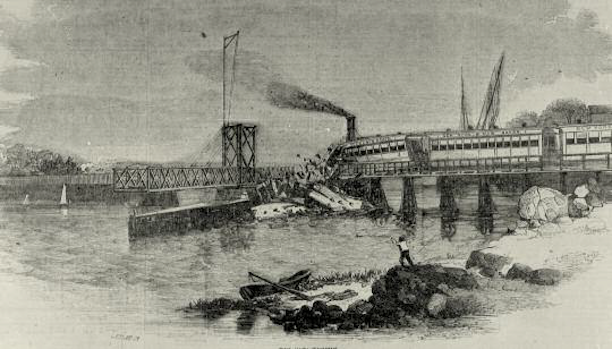

As Robert Shaw notes in A History of Railroad Accidents, Safety Precautions and Operating Practices, the bridge was “ordinarily closed to ships, and the [bridge] tender would open it upon their signal only when certain that no trains were approaching.” The tender lowered a red ball down a pole visible to trains 3,300 feet before the bridge to signal that the bridge was open and it was unsafe for a train to pass. Just as the bridge tender was about to close the span, however, the 8:00 express to Boston rounded the curve at 25 miles per hour.

The train plunged into the river; its speed carried the engine across the western channel, where it smashed into the central pier. All cars but one fell into the river. Dr. Russell, who was in the last car, reported in the May 7, 1853, Hartford Courant, “The front of the car and part of the floor had broken off just in front of me, one end resting on the bridge and the other on the cars in the water below.”

“Far too Many, Dead.”

Almost 40 victims in the first two passenger cars drowned. The crew from the Pacific pulled survivors from the water. Dr. Russell, too, aided in the rescue: “We immediately commenced taking out the inmates at the windows, and soon got out a large number, some injured, some bruised, and many, ah, far too many, dead.” Seven of those who died were Dr. Russell’s fellow doctors, including Dr. Archibald Welch of Wethersfield, president of the Connecticut Medical Association.

An inquest held Edward Tucker, the train’s engineer, negligent, since the bridge tender had displayed the signal that the bridge was open. Tucker and the train’s fireman were arrested. Although Tucker insisted he had seen the red ball aloft signaling it was safe to pass over the bridge, other witnesses testified that the ball had been lowered. Two years later, the New York & New Haven Railroad settled death claims amounting to an estimated $290,000.

Contributed by Emma Demar, a Connecticut Explored intern and Trinity College student in 2011, and Elizabeth Normen, the magazine’s publisher.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This passage originally appeared as part of the article “What a Disaster!” in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 9/ No. 4, Fall 2011.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.