By Rena Tobey

Imagine a Loyalist to the British king sitting for hours opposite a rebel who fought to overturn British rule. The ratification of the United States Constitution in 1789 brought them together. What did they talk about? Perhaps they did not talk at all. After all, the Loyalist was a painter, and the rebel was his portrait sitter. Not speaking would be fairly typical, but nothing in Ralph Earl‘s portrait of Mariann Wolcott conveys silence. Earl’s likeness of Wolcott suggests an easy rapport and admiring respect. In the work, he captures her rousing spirit and self-assurance. Perhaps she holds one soft glove to demonstrate grace, or gloves off, she is ready to fight for her point of view. This portrait leaves no doubt that 24-year-old Mariann Wolcott was a figure of fashion and force, befitting one who took shaping a nation literally into her own hands.

Mariann Wolcott Rolls Up Her Sleeves

On July 9, 1776, a broadsheet of the Declaration of Independence was read aloud to George Washington’s Continental army troops mustered in New York at the Battery in lower Manhattan. Against Washington’s expressed wish for order, the soldiers and young men of The Sons of Liberty jumped the tall protective fence of nearby Bowling Green Park. They then tied ropes around the equestrian statue of King George III and pulled it to the ground. The gilded lead statue smashed, and angry colonists then further hacked it into bits.

An idea formed for using the “leaden George.” Colonists painstakingly loaded pieces onto wagons and hauled them to the wharf before placing them on a schooner that sailed to Norwalk. From there men transferred the statue shards onto oxcarts and transported them to a foundry in Litchfield. General Oliver Wolcott, Mariann’s father, owned that foundry. The plan? To melt the former statue’s lead to form bullets. The exorbitantly expensive statue, itself a symbol of the taxation policies that led to colonial revolt, ironically became “melted majesty” to be fired back at British troops.

Craftsmen required one pound of lead to make 20 balls, and Mariann Wolcott kept careful accounting of the production of bullets in the Wolcott orchard. She tracked 42,088 bullets. Her mother Laura produced 8,378 bullets and her 10-year-old brother, Frederick, 936. Mariann herself formed 10,790, a figure representing a quarter of all the bullets produced from King George’s fallen statue.

An Artist Struggles Through the Revolutionary War

Meantime, Ralph Earl firmly allied himself with England, assessing his career as a portraitist to be more secure siding with affluent Loyalists. Disinherited by his father, a captain in the “rebel service,” Earl staged his own rebellion in March 1777. Acting as a British spy, he disclosed information about the “rebel army” plan to invade Long Island. Later, while in England, Earl requested recompense for this act. No record of a response survives.

When (in April 1777) the Committee of Safety in New Haven told Earl to “take up arms,” face imprisonment, or “quit the Province,” Earl chose the latter. He disguised himself as a servant to British Captain John Money, the Quartermaster General of General John Burgoyne’s Northern Army. They sailed to Newport under a flag of truce, then on to England. Earl used his time there to hone his artistic skills. He married Ann Whiteside, while his first wife, Sarah, and their daughter still resided in New Haven. But the painter felt the call to return home and in 1785, sailed for North America on the Neptune—borrowing money for passage.

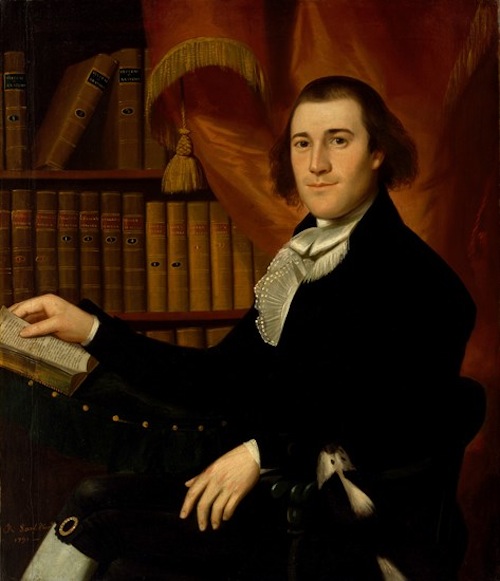

Ralph Earl, Dr. Mason Fitch Cogswell, 1791, oil on canvas – The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

In New York City, the profligate Earl landed himself in prison, for a debt amounting to less than $25. Earl was freed in 1788, and his court-appointed guardian, Dr. Mason Fitch Cogswell, helped Earl start over, yet again, in Connecticut. The talented artist reasserted himself into Connecticut society, traveling around the state to paint notables.

Oliver Wolcott Commissions a Painting

By 1789, when Connecticut Lieutenant Governor Oliver Wolcott commissioned Earl to paint his wife, his daughter Mariann, and himself to commemorate the ratification of the Constitution, Earl was at the peak of his career. So was Wolcott, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and just seven years away from serving as governor of his home state.

In his work, Earl shows Mariann Wolcott as more than just “one of the most distinguished beauties of her time,” as Samuel Wolcott wrote in his 1881 family history. She stands proudly in front of her family’s tidy fields. The illusion of depth suggests the Wolcott land holdings were vast, with the Bantam River snaking toward Litchfield, its white meetinghouse spire just visible in the distance. Mariann wears a cotton day dress, and her spotted muslin shawl, kid gloves, and fashionable parasol, all protect her skin from acquiring a working-class suntan. Her herisson (“hedgehog” in French) hairstyle, with its two soft ringlets and light powdering, was the latest rage. Anything but foppish and delicate, Mariann’s intelligence is what lingers, created with the painterly trope of light bouncing off her forehead.

Ralph Earl, Oliver Wolcott, ca. 1789, oil on canvas – Museum of Connecticut History

In October 1789, Mariann married Chauncey Goodrich, a lawyer in Hartford. She then wrote lively letters to her family, wittily advising her brother “in the mysteries of the female heart” and sharing her husband’s growing political prominence. In her portrait, the sprig of pink roses placed demurely at her bodice functioned as an air freshener, but also symbolized the bud of fertility and motherhood. Yet Mariann, once more, defied tradition. A month after marrying, in a letter to her sister-in-law, Elizabeth, she wrote, “As for being obedient and dutiful, tell [her brother Oliver] it is not in my creed.”

From her take-charge act early in the Revolutionary War to the celebration of the new country, Mariann Wolcott stood in contrast to the opportunistic artist Ralph Earl. The coming together of these divergent temperaments with her portrait immortalizes that fascinating encounter.

Rena Tobey is an American art historian, providing talks and tours around the state. She has also created Artventures! Game—a party game on the adventures of art and art history.