by Peter Vermilyea

Street names are often guides to a town’s past. In Litchfield’s case, this is perhaps most graphically illustrated by Gallows Lane.

Once called Middle Street, its 28 rod span (154 feet) made it the widest in Litchfield. Most town residents have heard the story that the street got its current name because executions once took place there. The historian–trained to be a skeptic–questions this piece of lore. But it’s true. And the story reveals crimes of a bloody nature we don’t often associate with our forefathers.

Barnett Davenport was born in the Merryall section of New Milford in 1760. At 16 he joined the Continental Army to fight in the American Revolution. He served under George Washington and was at Valley Forge, Fort Ticonderoga, and Monmouth Court House. He had been a troubled youth and was a convicted horse thief. Perhaps because of his demons, or because he had simply had enough of war, Davenport deserted and returned home.

Robbery, Arson, and Murder

He took a job with Caleb Mallory, a farmer who operated a grist mill along what is now Route 109 in Washington. Mallory and his wife Jane had two daughters who lived in the area. One of the daughters had three children: a daughter Charlotte, nine years old, and sons John and Sherman, ages six and four. In February 1780, Davenport convinced Caleb’s two daughters to go on a trip. With the two away from the house, Davenport entered the home on the night of February 3rd and beat Caleb, Jane, and Charlotte to death. Looting the house of its valuables, he set it ablaze as he left, killing John and Sherman.

Davenport escaped on foot and hid out in a cave in Cornwall for six days. Captured, he was brought to Litchfield where he was arraigned and gave a full confession, likely to Reverend Judah Champion of Litchfield’s Congregational Church. The confession is now in the archives at the University of Virginia.

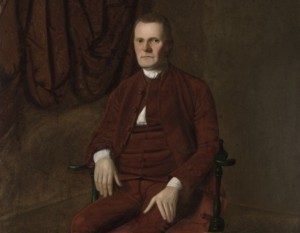

Ralph Earl, Roger Sherman, ca. 1775, oil on canvas

– Yale University Art Gallery

Davenport’s trial was presided over by Roger Sherman, who previously had served on the committee that wrote the Declaration of Independence. Sherman sentenced Davenport to 40 lashes and then to be hanged. The execution took place at Gallows Hill on May 8, 1780. The hill, as it name implies, served as an execution site. In 1768, a Native American named John Jacob had been hanged there for the murder of another American Indian. In 1785, Thomas Goss of Barkhamsted was also hanged on the hill, for the murder of his wife.

Davenport would likely have been led in a procession from the Litchfield jail to the site of the gallows. It was quite common in early America for large crowds to turn out for an execution, as it was considered an opportunity for moral instruction for children. The sheriff would read the sentence to the condemned, who would be hooded and mounted on the stand. A minister would give a sermon. With the noose placed around Davenport’s head, the trap door was sprung. The body would be left hanging for some time, a reminder to passersby of the dangers of immorality.

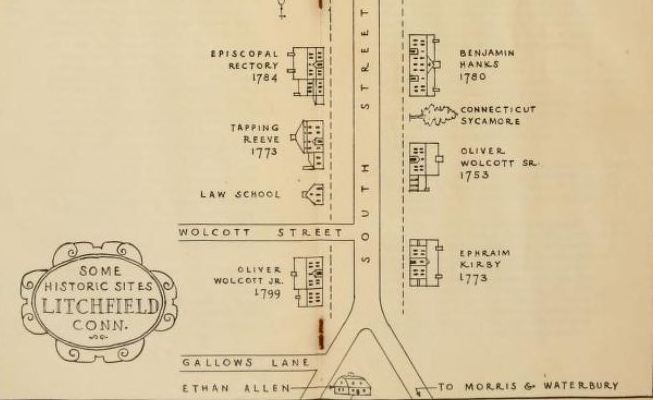

Detail of a map from Some Historic Sites of Litchfield, Connecticut by the Litchfield Historical Society

Peter Vermilyea, who teaches history at Housatonic Valley Regional High School in Falls Village, Connecticut, and at Western Connecticut State University, maintains the Hidden in Plain Sight blog and is the author of Hidden History of Litchfield County (History Press, 2014).

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.