By Gregg Mangan

By 1895, Albert Augustus Pope’s Columbia bicycles were a national phenomenon and his Hartford-based Pope Manufacturing Company was the largest employer in New England. Not only had Pope used what one employee called his “master showman’s mind” to popularize his products and turn Hartford into the bicycle capital of the world, he also proved able to predict trends in the transportation industry.

Pope placed himself among the leaders in adapting to these changes. For example, in an effort to expand the market for his products, he became an advocate for improving the nation’s roadways. Later, anticipating the popularity of motorized transportation, Pope built plants capable of producing more than 2,000 automobiles per year, making him America’s leading automaker at the turn of the 20th century. The obstacles he faced in his efforts to bring quiet and clean-running electric cars to market presaged the challenges later automakers would encounter.

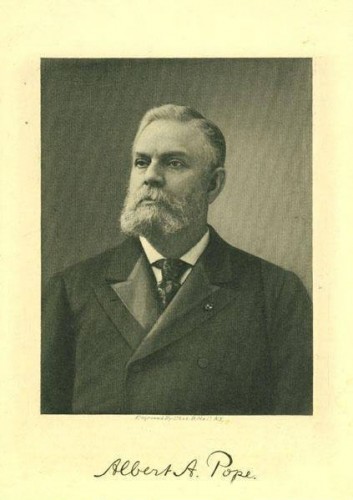

Albert A. Pope, 1900 – Connecticut Historical Society

Early Life

Albert Pope, born on May 20, 1843, was the fourth of eight children born to Charles and Elizabeth Pope of Boston, Massachusetts. Charles was born into a 200-year-old family legacy of success in the lumber industry. Rather than join the family business, Charles opted to go out on his own and began a career in real estate speculation. Initial prosperity quickly turned to despair when his business collapsed in 1852. During this time, nine-year-old Albert went to work plowing fields on a neighbor’s farm. At age 12, he began selling fruits and vegetables, and by age 15 he had dropped out of school and taken a job working at Quincy Market.

In 1871, Pope married Abby Linder, with whom he had six children. By then he was a Civil War veteran, having joined the 1st Company, 35th Massachusetts Volunteer regiment at 19 and gone into battle under the command of such notable generals as Ulysses S. Grant and Ambrose Burnside. He was named a lieutenant colonel for battlefield bravery and was referred to as “Colonel Pope” for the rest of his life. After the war, he started a shoe-supply business with $900 he had saved while in the Union army. In less than a year his business was the largest of its kind in the country.

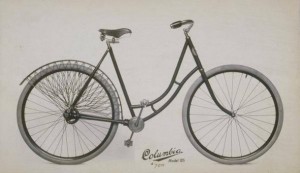

Columbia Bicycle Model 105, 1903 – Connecticut Historical Society

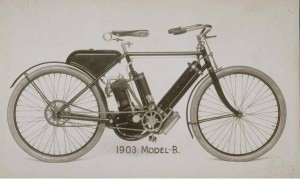

Columbia Bicycle Model B, 1903 – Connecticut Historical Society

Pope Sees Future in the Bicycle

The 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia was the turning point in Albert Pope’s professional life. There he saw his first bicycle and became so enamored of it that he sped off to Europe to study how bicycles were made. After acquiring the American rights to the patents, Pope approached the Weed Sewing Machine Company about using the empty wings of its Hartford plant to produce 50 “test” velocipedes (a catchall term for early foot-powered vehicles with one or more wheels). Pope’s two-wheeled models proved such a success that the plant was soon producing more bicycles than sewing machines. By the end of the 1880s, the Weed factory was producing 5,000 bicycles a year, and Pope, who was by then selling his product nationally, bought the plant outright.

A knack for advertising to the masses contributed to Pope’s success, as did controlling the supply chain for his products—an approach to innovation that lowered costs and broadened his customer base. For example, in 1892 Pope brought much of the material production in-house, buying the Hartford Rubber Works, a steel company, and the largest nickel-plating factory in the world. Now in control of the production of his raw materials, he sought new ways to lighten the weight of his 70-pound bicycles.

Design Improvements Expand Market

By hollowing out the bike’s steel tubes and limiting wheel friction, he was able to make his bicycles lighter and easier to pedal, allowing him to expand the market for his bikes to women and children. Women in the late 19th century were quick to embrace the new-found sense of freedom and mobility that came with bicycling. So closely associated were bicycles to the concept of independence and liberation, that civil rights activist and suffragist Susan B. Anthony declared, “The bicycle has done more for the emancipation of women than anything in the world.”

Pope and the Good Roads Movement

Closely tied to the opportunity to expand the market for bicycles was the need for higher-quality roads on which to ride them. In the late-19th century, roads outside of major cities were largely comprised of rutted dirt paths. Pope recognized just how essential good road conditions were for increasing his sales and improving the ability to move supplies and products in and out of his Hartford facilities. In 1880, he founded the Good Roads Movement and the League of American Wheelmen, an organization meant to promote greater government participation in building America’s roads. Pope encouraged teachers to begin instructing students on road building as early as kindergarten, and he lobbied the United States Congress to create a government department in charge of roads. In “A Memorial to Congress on the Subject of a Road Department” in February of 1893, he stated his case very clearly:

The people everywhere throughout the country are awakening to the vast importance of better highways. They more fully realize not only the great commercial advantages of good roads but they see more clearly that the material highways of the country are highways in a spiritual sense as well; that the growth of society, education, and Christianity depend largely upon good means of communication between home, school, and church, and that no nation can advance in civilization which does not make a corresponding advance in the betterment of its highways.

Hartford Leads Early Automobile Industry

By the 1890s, experiments with the internal combustion engine were set to bring about the next revolution in the transportation industry, and once again Albert Pope intended to be at the forefront of the change. Sensing the decline of the bicycle as dreams of motorized transportation spread across the country, Pope created an automotive division within his Pope Manufacturing Company.

Advertisement for the Columbia Chainless Bicycle, 1897 – Connecticut Historical Society

While most manufacturers were developing new and better gasoline-powered cars, Pope was confident that clean, quiet, electric cars would be the wave of the future. In 1896, he founded the Columbia Electric Vehicle Company in Hartford and, a year later, demonstrated the world’s first public production model electric-powered car. His production of 2,092 cars (some gas-powered) in 1899 accounted for nearly half the automobiles made in the United States, but his attachment to producing electric vehicles eventually became his downfall.

Electric storage batteries were heavy and incapable of holding charges for long periods. Meanwhile, new and abundant supplies of petroleum provided gas-powered vehicles with an edge over their electric counterparts. Pope’s efforts were further hampered by the prohibitive costs of shipping raw materials to New England, and he began to lose ground to his Midwestern competitors. A plan to generate wealth through the pursuit of patent-infringement lawsuits redirected Pope’s energies away from technology and innovation, allowing men like Henry Ford to surpass him as the nation’s leading automaker. Eventually, auto production’s industrial base shifted out of Connecticut and into the Midwest.

A brief foray into silver mining in 1901, followed by an unsuccessful attempt to resurrect his failing bicycle and automotive empire, led to financial ruin. Pope spent his remaining years with his family in Boston until his death on August 10, 1909. The Hartford Courant listed his cause of death as “locomotor ataxia,” a diagnosis used to cover an array of symptoms usually associated with Parkinson’s disease or the late stages of syphilis.

A Transportation Legacy

Albert Pope’s pioneering work in the transportation industry is still pertinent today. In an age when railroads shuttled large groups of people across the country, Pope recognized the consumer’s desire for more personal modes of transportation that would allow them to go where they wanted, when they wanted. He saw the potential of both the bicycle and the automobile to satisfy the individual American’s desire for independence and mobility.

Pope’s efforts to improve the nation’s roads helped fuel the expansion of communication and commerce that characterized post-industrial America. Albert Pope did more than build a financial empire that made Hartford the bicycle and automobile center of the nation; he changed transportation in the United States and altered the nation’s beliefs in what was possible by presenting new and innovative glimpses into the future.

Gregg Mangan is an author and historian who holds a PhD in public history from Arizona State University.